Book Review by George S: The Ship was first published in 1943, when the outcome of the war was still uncertain, and it bears the marks of a book composed for the purposes of propaganda.

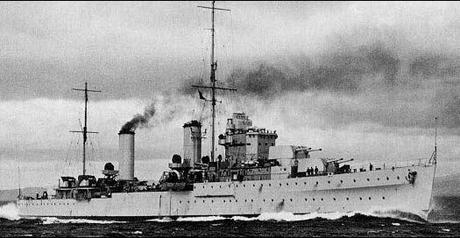

HMS Penelope, the light cruiser on which the Artemis was based.

HMS Penelope, the light cruiser on which the Artemis was based.

It is the story of the Artemis, a light cruiser accompanying a convoy of merchant ships to the besieged island of Malta in 1942. Forester reminds us frequently of the crucial role of Malta at this stage in the war; if the convoy, with its vital supplies is prevented from reaching the island:

Then Malta would fall; the running ulcer in Italy’s side would be healed; Rommel in Africa, the submarines in the Atlantic would feel an instant lessening of the strain upon them; the Vichy government would be informed of one more step towards the German conquest of the world; the very Japanese in seas ten thousand miles away would be aware of a lightening of their task.

The convoy is threatened by a considerable portion of the Italian navy, including battleships whose armaments easily outclass those of any of the British ships.

The action of the novel covers a few hours, during which the Artemis takes aggressive action against the Italian ships. Each of its chapters is headed by a phrase from the Captain’s official report on the incident – for instance ‘At 1205 smoke was sighted’, or ‘Action was taken in response to orders previously issued.’ The chapter then shows the reality behind the laconic, conventional phrasing; so that, for example, the phrase ‘a hit started a small fire’ introduces a chapter that details the devastation fire can cause on a small ship:

The heat of the explosion was like the heat of an oxy-acetylene flame, like the heat of an electric furnace. The paint on the bulkheads of the wardroom was only the thinnest possible layer – kept thin with this particular emergency in view – but it burst into raging flames, as if the very plating had caught fire. The scant covering of linoleum on the deck burst into flames. The padding of the chairs caught fire. The bulkhead forward, dividing the wardroom from its stores, had been torn open, and the stores caught fire, all the sparse pitiful little things which brought some amenity into the lives of the officers: tablecloths and table-napkins, newspapers and spirits, the very bread and sugar, all blazed together.

Most chapters introduce us to at least one new member of the crew. There are six hundred men on board, and we meet a representative sample of them, and learn something of their characters, as well as what each contributes to the efficiency of the ship in action. Inevitably, many of the characters are to some degree stereotypes (the officer afraid of showing his fear, the old sweat, the technician obsessed by his work, and so one) but Forester is a skillful enough writer to keep us interested in them. Above all, he wants to show how they work together, as a team in which every member is crucial.

Forester’s previous naval books (Brown on Resolution and the Hornblower series) had focused on individuals – Hornblower lonely in command and Brown stranded by himself, using his initiative – but this is very much a group portrait. The Captain has some of Hornblower’s qualities (especially the gambler’s instinct to push his ship as far as it will go, and the Nelson decisiveness that keeps him taking the offensive against the odds) but he is only one of those whose actions and steadfastness are crucial to the success of the operation.

Forester stresses the Artemis’s flimsiness in the face of the enemy’s superior strength:

It was her duty to smite, even though to smite she must expose those eggshell sides of hers to the sledgehammer blows of the enemy, and run the gauntlet of one-ton shells hurled with the velocity of a meteor, with an accuracy which could hit a tennis court from ten miles distance.

The novel very graphically brings home the dangers and terrors of life at sea. Its original readers would have been very aware of the desperate situation of Malta in 1942, and would have read news stories celebrating the success of Operation Pedestal, the crucial convoy that made it through to the island in August 1942.

The novel is very much a ‘People’s War’ book. It hammers home its morale-building message that the Artemis’s success was a team effort, not only by its very deliberate inclusion of the whole ship’s company in the account, but in a long bravura sequence that traces the life-story of the crucial six-inch shell whose explosion will change the course of the battle in favour of a British victory (and so change the course of the war). It begins in the factory, paying homage to the civilians:

For the correct apportionment of the credit the history of that shell and the charge which sent it on its way should be traced back to their origins. There were, somewhere in England, women whose skin was stained yellow by the picric acid which entered into the composition of the bursting charge, who sacrificed strength and beauty in the munitions factory that filled that shell; their hair was bound under caps and their feet encased in felt slippers lest the treacherous material they handled should explode prematurely. There were women at the precision lathes who turned that shell until it fitted exactly, to the thousandth of an inch, into the rifling of the gun that fired it. There were the men that mined the iron and the coal, and the slaving foundry workers who helped to cast the shell. There were the devoted sailors of the Mercantile Marine, who manned the ship that bore the nickel that hardened the steel from Canada to England, in the teeth of the fiercest blockade Germany could maintain. There were the metallurgists who devised the formula for the steel, and there were the chemists who worked upon the explosive. There were the railwaymen and the dockyard workers who handled the deadly thing under the attack of the whole strength of the Nazi air power.

And so on, until the shell reaches the ship, where its progress from the magazine to the gun on this crucial afternoon is traced, with acknowledgement given to every man who did his duty, as he’d been trained to, to ensure that it has its chance to make its mark.

The Artemis was based on HMS Penelope, to whose ‘Officers and Ship’s Company’ the book is dedicated. Based at Malta, the Penelope endured so much damage from bomb fragments that she was nicknamed ‘HMS Pepperpot’.

I was enthralled while reading this book, but I should confess that it is not a novel I can review very objectively. From 1940 to 1942, my father was stationed in Malta, in command of the minesweeper Abingdon. German bombers did for the ship in April 1942, shortly before the events of this novel. Forester was a favorite author of his, and I remember him taking The Ship from our local library more than once. I don’t know why I haven’t read the book before.