Seeing Bruce Robinson attached to The Rum Diary made me want to see the adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson's novel far more than even Johnny Depp's return as the writer's stand-in. The writer-director made the greatest movie yet made about the bleak (and bleakly comic) effects of spiraling alcoholism, Withnail and I, making him theoretically perfect to bring the early days of Thompson to life. However, not five minutes passed before I instantly realized he was precisely the wrong person for this film, and the rest of the film only proved me right.

Seeing Bruce Robinson attached to The Rum Diary made me want to see the adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson's novel far more than even Johnny Depp's return as the writer's stand-in. The writer-director made the greatest movie yet made about the bleak (and bleakly comic) effects of spiraling alcoholism, Withnail and I, making him theoretically perfect to bring the early days of Thompson to life. However, not five minutes passed before I instantly realized he was precisely the wrong person for this film, and the rest of the film only proved me right.The Rum Diary, Thompson's fictionalized account of his time in Puerto Rico as a struggling writer, itself embodies a sense of emergence in the author. Imperfect as the book is, it shows Thompson on the cusp of finding himself, precisely through the substances that would later derail him. It is in Thompson's most booze-soaked, tongue-loosened moments that The Rum Diary foretells the man who would win infamy by spilling out his chemically rotted brain with each article. But Robinson's depiction of the cult hero's excess carries a sense of foreboding irony that would make him the perfect choice to survey the writer's late career, not the birth of his inspiration.

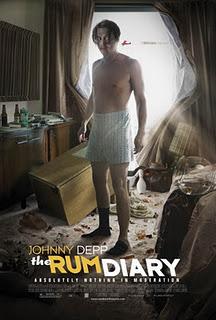

Robinson's Diary opens on the bloodshot eye of Thompson's ersatz self Paul Kemp (Johnny Depp) awakening to his first morning in Puerto Rico, where a circling biplane outside his hotel already spoils his view of the natural beach. We've just started and already it feels like the end of the party, and Paul hasn't even figured out how to get into the room fridge yet for the booze! Thompson hasn't even fully discovered drink, much less drugs, and Robinson is already wringing his hands over where it will lead.

Paul stumbles into work at his new gig at the San Juan Star, an English-language paper for the tourists who come to the American territory and never leave the hotel. The real Thompson was so green at the time that he couldn't even work at this place, and it's hard to imagine him doing so even if he could. Robinson doesn't resort to a montage to get the point across, instead letting a single scene of Paul interviewing a brain-dead bowler so rotund he resembles the cartoon humans of Wall•E and his xenophobic wife speak volumes about the insipid capitalist oblivion being sold to these sheltered white people. Outside hotel walls, Puerto Ricans live in extreme poverty, and the paper's editor (Richard Jenkins) dismisses any attempt to write about that hard truth. He says the paper exists to sell the visitors on the idea that they're living the American Dream, a term he uses so insistently and ironically it comes to resemble Milo's mantra of everyone having "a share" in his syndicate in Catch-22.

That open disdain for corrupting capitalism buoys the film, though its human embodiment, Sanderson (Aaron Eckhart), eventually drags down the narrative. On his own, Sanderson is a brilliant caricature, such a sell-out that his senses bypass normal perception for greed. He looks out over a crisp blue ocean and sees only money, planning to insert hotels and marinas that will soon turn those waters to polluted sludge and prevent the actual natives from ever seeing the ocean again, locked as they'll be behind private property fences.

Tied to his girlfriend Chenault (Amber Heard), however, Sanderson's avarice comes to offend Paul for petty reasons of jealousy rather than political disgust. Sanderson is already everything Thompson hates, so to define him primarily by his relationship to Paul's love interest cheapens the character's impact. Furthermore, the chauvinism Sanderson displays toward Chenault is meaningless considering the sexist light in which Thompson cast her, a problem Robinson fails to rectify.

Thompson's formulating political stances thus softened, it falls to his tentative discovery of the more dangerous side of substance abuse to float the film. But, as has already been said, Robinson's direction is simply too sober for what The Rum Diary needs to be. His dimmed, earthen-toned lighting resembles that of a Hopper painting, communicating a sense of loneliness and despair that clashes with the fiery indignation slowly rising in Thompson/Paul's throat like booze he hasn't yet figured how to keep down. It's the same oaken palette as Withnail and I despite showing a far more colorful location and story, transplanting the open-casket-reception tone of the former into an incongruous situation.

The Rum Diary occasionally works, even within its vaguely moralizing aesthetic premise. Giovanni Ribisi is hilarious as the half-decipherable Moberg, whose slurring shuffle and exaggeratedly bum-like appearance works as a makeshift Ghost of Christmas Future for our good Raoul Duke. Depp's impression is coherent here, revealing the presence of brain cells not yet eradicated by a cocaine- and bourbon-fueled genocide, but Ribisi shadows him with promises of mumbles and mood swings to come. To clarify, Robinson does not disserve the film by hinting at the dark road upon which drugs and alcohol will place Thompson. If anything, this film lacks the power of Withnail and I in demonizing hollow, joyless hedonism. That film ripped off crusted scabs while also finding the humor in its hopelessness; this just feels like a demented after-school special. The Rum Diary is a story that openly builds to the optimism of substance use, and Robinson can't square that with his (admittedly more mature) hindsight. It just doesn't work, robbing an already scattershot work of its flashes of power, insight, and groundwork laying.