By Larry Rohter

THE NEW YORK TIMES: ARTS ABROAD

Published: December 13, 2001

(Editor’s note: Here is another timely article. Although published more than a decade ago, Larry Rohter, who was The New York Times’ South American bureau chief from 1999 to 2007, wrote about the entertainer Carmen Miranda, Brazil’s most famous cultural export, and the musical show, South American Way, which premiered in Rio in 2001. At the time, Carmen was ripe for reevaluation, with most Brazilians expressing curiosity about her image and style. With the 2005 release of journalist Ruy Castro’s masterful book, Carmen – Uma biografia, the real story behind the tutti-frutti façade could now be told about Miranda’s North American exploits. Perhaps in the near future, the Brazilian Bombshell may once again establish a presence on the stage of the Great White Way.)

RIO DE JANEIRO — She may be the most famous person their country has ever produced, but Brazilians have always had mixed feelings about Carmen Miranda. Yes, she made Brazil better known all around the world, but did so by playing scatterbrains and reinforcing every condescending stereotype the Anglo-Saxon world has ever had about Latin Americans.

Her detractors here have always complained that she wasn’t even a ”true” Brazilian, having been born in Portugal, and that a white woman living in a Hollywood mansion had no right to sing a style of music born in black slums.

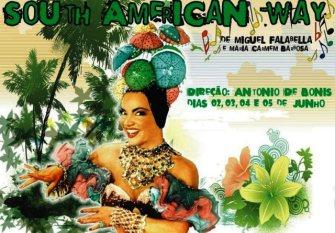

That deep-seated ambivalence is the focus of South American Way: The Carmen Miranda Musical, a hit play here that deliberately reopens those old wounds. While acknowledging all the criticisms Brazilians have traditionally leveled at Miranda, the play takes an ultimately sympathetic view of the life and career of modern Brazil’s first entertainment export.

Miguel Falabella

”We wanted a piece that would entertain, but at the same time be provocative and authentic,” said Maria Carmen Barbosa, who wrote the play with Miguel Falabella. ”We wanted to talk about image and self-image and call attention to the confusion of culture and language that Carmen personified, so that she wouldn’t be seen just as that crazy woman who has inspired a million transvestites.”

South American Way is the most visible manifestation of what can only be called a reassessment of Miranda under way in Brazil. She was a subject of Brazil’s pavilion at the recent Venice Biennial, the singer Ney Matogrosso recently released an album of songs associated with her and her relevance has been the subject of a comic revue.

”Carmen hasn’t been forgotten, but she’s been kind of ignored or neglected in recent years,” said Mr. Falabella, who is also the play’s director. ”But now there’s a whole new generation of people who are curious about her, who have an open mind and want to know who she really was and what she represented.”

South American Way elaborates on the revisionist image first presented in the Brazilian director Helena Solberg’s Bananas Is My Business, a ”fictional documentary” released in the United States in 1995. That film offered a politicized vision of Miranda as a martyr sacrificed on the altar of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy, which sought to inspire amity in Latin America to help the Allies win World War II.

As many Brazilians see it, Miranda was a willing accomplice, denying her Brazilian identity in favor of some nebulous Pan-American composite. In more than a dozen movies that she made in Hollywood, she played characters with names like Rosita, Paquita, Dorita and Chiquita, often speaking a mangled English that wounded Brazil’s image of itself as a rising power different from the rest of Latin America.

”Lots of people here still think she was nothing but a caricature,” Mr. Falabella said. ”She obviously colluded in that, but who wouldn’t have? Who would have said no to Hollywood at that time?”

Ney Matogrosso (alienado.com)

Starting with its title, South American Way [an ersatz rumba written by Al Dubin and Jimmy McHugh] gently mocks the inability of North Americans to tell Brazil from Argentina from Mexico from Cuba — a sensitive topic here even today.

”For all the talk about a globalized world, this continues to be a real problem for us,” Mr. Falabella said in an interview. ”I’ll go online to a chat room and be talking with someone from Iowa who asks me where I’m from, and when I say Rio de Janeiro the answer that comes back is, ‘Where is that?’ ”

The play also addresses the contentious issue of Miranda’s place within Brazilian culture and the authenticity of her music. Though she came to be known abroad as the Brazilian Bombshell, Miranda never became a Brazilian citizen, for reasons that are still the subject of debate and some resentment here.

”Even though Carmen was Portuguese, she assimilated all of Brazil and had a Brazilianess that few Brazilians have,” Ms. Barbosa said. ”She was irreverent, had street smarts, wit, daring and an impressive innate musicality.”

Over the years, Miranda has also been criticized on racial grounds, first by those who thought it déclassé for her to embrace the samba, black Brazil’s main form of expression, and more recently by black militants who accuse her of expropriating their culture. The famously elaborate headdresses she wore, for example, can be seen either as homage to or a camp parody of those worn by black women in Bahia, Brazil’s most Africanized state.

South American Way (temmais.com)

Her admirers today prefer to see Miranda as the Brazilian equivalent of Elvis Presley, ”a white man who sings black music and takes it to a larger audience,” Ms. Solberg said, adding: ”Yes, she was a European with green eyes who sang black music, but that is one of the reasons the upper classes attacked her. We had a very colonialized mentality at that time, and samba was seen as being a thing from the slums, for and by blacks and not proper.”

Miranda’s friendships with black and mulatto songwriters, which is portrayed in ”South American Way,” was so unusual that when she arrived in Hollywood, ”the darker members of the Bando da Lua were gradually eliminated,” Ms. Solberg noted. She said studio executives preferred that Miranda appear with ”a group that had what they considered to be a typical Latin appearance, sort of Mexican-looking.”

This being Brazil, the land of carnival, serious subject matter is wrapped in seductive music, including most of the songs associated with Miranda, as well as lavish spectacle – ”delirious kitsch,” to use Mr. Falabella’s phrase.

South American Way features a cast of nineteen, innumerable costume changes and stars Soraya Ravenle as the buoyant, striving young Carmen, and Stella Miranda, no relation, as the depressed and isolated older Carmen.

Stella Miranda as Carmen

The debate over cultural confusion that is central to the play extends even to its structure. Depending on which critic you read here, it is either odd or only fitting that Miranda’s story be told in musical theater, typically a North American genre.

”But the content is totally Brazilian,” Ms. Barbosa said.

Indeed, South American Way includes some cultural references that may need to be explained to outsiders. The theater where the play is being performed, for instance, has been redecorated to evoke the Urca Casino, a Rio nightclub where in 1940 she was met with stony silence when she took the stage in what she had hoped would be a triumphant performance for a hometown crowd after returning from Hollywood.

The incident was so painful that she fled back to the United States and did not return to Brazil for fifteen years, until shortly before her death at age 46. Her funeral was ”the best attended in the history of Rio,” noted Cássio Barsante, her biographer, but she soon became almost irrelevant.

To the generation that came of age in the 1960′s and now dominates Brazilian culture, ”Carmen was more an absence than a reference in conversations about popular music in post-Bossa Nova Brazil,” the composer Caetano Veloso wrote in his autobiography. Her Hollywood success, he added, ”made her into a figure of caricature that we grew up feeling somewhat ashamed of” because she projected the image of ”a sexually exposed, exaggeratedly colorful and fruity Brazil.”

But that is precisely one of the images that the new play embraces.

”Brazil will only be able to truly be Brazil and achieve greatness when it accepts its tropical exuberance,” Mr. Falabella said. ”It’s time we stopped having an inferiority complex about that and regained our self-esteem.”

Copyright © 2001 by The New York Times