What did those words in the Declaration of Independence, the pursuit of happiness, really mean? This is explored in a book with that title by legal scholar Jeffrey Rosen, subtitled How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America — reviewed by Bill Shapiro speaking at the Albany Public Library.

Those men had an understanding of those words different from ours. They were steeped in classical philosophical writings — Adam Smith, David Hume, Montesquieu, John Locke; and ancients like Xenophon, Plutarch, Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius. (Plato not mentioned; we wouldn’t want to live in the sort of polity he idealized.)

We all think we know what happiness means. Yet it’s not so simple.* Happiness in a given moment is something very different from living a happy life. An applicable word from the Greeks was eudaimonia — connoting a life well lived.

Particularly relevant was Cicero’s essay, “What is Happiness?” He equated it with virtue, in turn meaning balance, which means passion moderated by reason. Or, not merely feeling good, but being good. A quest rather than a destination.

That’s all very general. But Benjamin Franklin concretized it into a list of specifics: like temperance, orderliness, resolution, frugality, industry, humility. Toward the end of his life he deemed pride the hardest passion to subdue. And in that regard Franklin was proud of his humility.

All this resonated for me. I too feel passion — moderated by reason. My ego is powerful, but keeping it contained is a key principle of humility of which I too am deeply proud. (No contradiction between feeling and behavior.)

Meantime all this philosophizing provided the subtext when our founding fathers gathered to craft a constitution in 1787. Madison, a sort of protege of Jefferson (away serving as ambassador in France), took a leading role, after purposefully immersing himself in those classical theorists. Leading to two central concepts.

One, derived from Montesquieu, was separation of powers. Actually a quite novel idea at the time, virtually without historical precedent. But a way to resolve the founders’ fears of overweening government — after all, they’d just fought a war against one, with a king they thought tyrannical (and Britain was itself, actually, among the freest of nations). A system of checks and balances would keep government within bounds.

That also would, they hoped, imbue moderation. Deemed needful in promoting general happiness, again following Cicero. Making the personal political.

This all sounds so pure. But of course creating this novel governmental blueprint required balancing a lot of competing and incompatible interests, a messy imperfect process. The founders being, indeed, faulted for a lapse of sincerity in failing to reconcile the high-minded principles of liberty and pursuit of happiness with, in particular, the nasty reality of slavery. Yet that would have expected way too much of mere mortals in an imperfect world. It’s far from clear that there was a better blueprint available to them.

But their counting a slave as three-fifths of a person is widely misunderstood. It wasn’t a judgment on slaves’ human standing. The Southern states wanted them to count fully as population for purposes of apportioning Congressional seats, which would have greatly boosted their power. The 3/5 rule was a compromise on that. Hated even by James Wilson who devised it, Rosen noted.

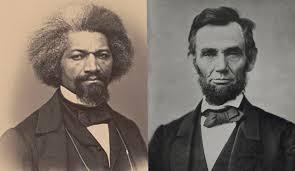

And of course that kludge didn’t stick. The eventual Civil War being seen as America’s “second founding,” really the theme of the Gettysburg address. Shapiro talked in particular about Lincoln’s relationship with Frederick Douglass (both of very limited formal education).

Douglass called out Lincoln’s wishy-washy abolitionism; but Lincoln saw his mission in larger terms; and his second inaugural speech (invoking “the better angels of our nature . . . with malice toward none, with charity for all”) Douglass called “a sacred effort.”

All this history is part of my soul, imbuing a profound appreciation of what America truly represents. Sure we’ve had crimes, what nation hasn’t? But America’s greater story is, through it all, the better angels of our nature battling down the demons every human society harbors. Indeed, uniquely among nations in all the world’s annals, that battle is the heart of America’s story.

But today, with ever fewer people internalizing that story, we’re at a crossroads, beset with passion unmoderated by reason. On the precipice of throwing it all down the toilet. That will break my heart.

* I’ve written about this: https://rationaloptimist.wordpress.com/2018/07/23/what-is-happiness/