Confessions © Samantha Groenestyn

I’ve been chewing over the role of a ‘conceptual rationale’ in art. Firstly, let it be recognised that I am not against concepts in art. Paintings should move us, and when they do they are more than mere decoration. But I am not interested in the types of concepts that only resonate in words, and that are swallowed whole in little capsules of artists’ statements, no chewing required. The real punch, the real power of art, is that it can make us sense something, consider something, meditate on something, and even feel something, just by channelling carefully composed signals through our eyes. I want to argue that while many a painting lacks a punch line, or fails to explain itself in words, it may still be about something, still built on an idea, and it may still speak softly to us, and perhaps even resonate fiercely with us as our history with it deepens. In Delacroix’s (p. 41) words, ‘What moves men of genius, or rather, what inspires their work, is not new ideas, but their obsession with the idea that what has already been said is still not enough.’

A humble painting of an interior sits shyly beside an unlovely outburst of so-called modern conceptual art. Without being punched in the face by unpleasant truths and by the sheer disgustingness of waste in our culture, the modern art viewer can find no meaning to lock on to when confronted with a work of art. Our time certainly is not one for subtlety, and images that demand too much of us are bound to be dismissed. Perhaps we feel an attraction to a still life scene, but sense that it would be too much work to justify this attraction—and, further, perhaps we feel a certain impatience with the painter for not simply being more clever about it so the painting’s relevance was immediately obvious. Whichever way I look at it, we are faced with a paradox: the painter wants to speak in a language that no one wants to learn. And even when he gets through to us, we cast off his whisperings as meaningless.

Yet, ‘If images don’t do anything in this culture, if they haven’t done anything, then why are we sitting here in the twilight of the twentieth century talking about them?’ art critic Dave Hickey (in Poynor, p. 43) asks. Hickey argues that the power of many images can be traced to beauty, ‘to the iconography of desire,’ but I want to return to beauty shortly. It seems to me that while many paintings certainly are beautiful, they appeal to us in another even simpler way. They permit us to look at ourselves.

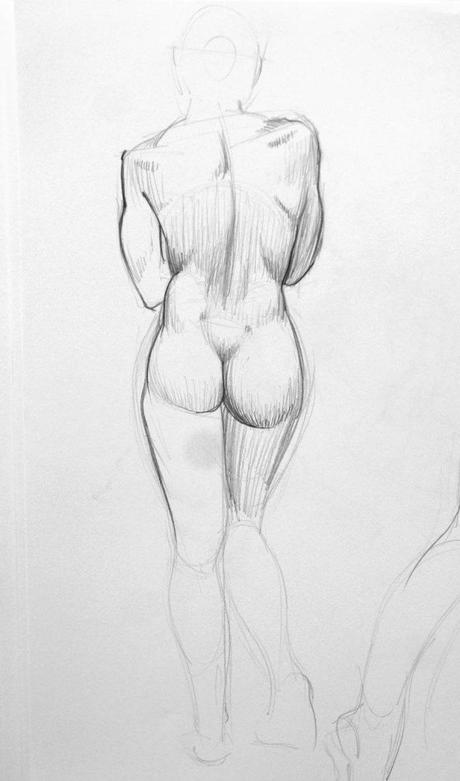

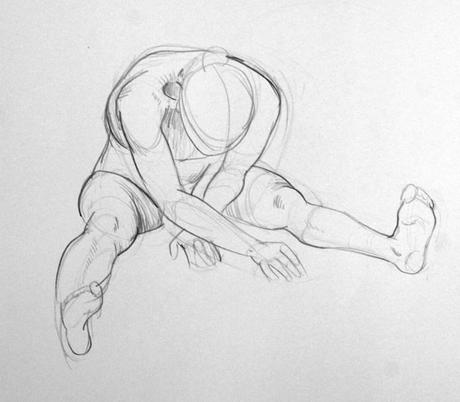

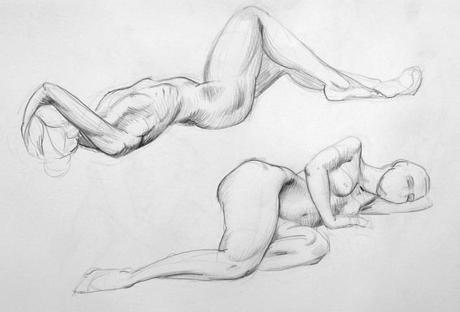

In the words of Jacques Pienaar, ‘If ever art had a job to do, it’s to make humanity look at itself.’ This might be as literal as a portrait of a known individual. It might be a nude—revealing our physical form at its simplest and most honest, unadorned, plump or bony, asymmetric, uniquely proportioned, secret toilet parts included (unlike the false view of ourselves afforded, for example, by much pornography). It might be the warmth of the painter’s home, traces of their life left in the arrangement of their living quarters. It might be a five-hundred-year-old Dutch breakfast, which can fill us with envy as much as the meals at the table next to us in a café today. Whatever else a painter may have intended, when painting from life he or she has done humanity a marvellous service in making a visual record of our temporal intersection with the physical world. Our cumulative knowledge has been recorded by philosophers and scientists; our successive sensory experiences have been recorded by artists—and what a vault of lived human experience remains! And further: no amount of adding to this collection is redundant, for we live in ever changing times and our present experiences are just as valid, as is the recording of them.

Of course, art is not always truthful, but there is also meaning in this. Where a representational painting sweeps some things away and introduces others, or chases a particular light or settles into a particular mood, the painting itself becomes a sort of bridge to the future. We see the world now, but we are also permitted to see a possible future through the vision of the painter. Frank Chimero (p. 68) argues that ‘every time we tell an untruth, we confess that the world is not yet done.’ He cites art historian George Kubler (p. 122): ‘The moment just past is extinguished forever, save for the things made during it,’ adding, ‘All of these creations linger, and they echo across the long line of time and speak to what those people were able to build and what they believed.’

Let us return to Dave Hickey and his efforts to direct our attention ‘to the language of visual affect—to the rhetoric of how things look—to the iconography of desire—in a word, to beauty!’ Wendy Steiner (xxi) analyses the twentieth-century discomfort with beauty, the prevailing suspicion that beauty is the villain—‘a siren or a whore.’ Steiner suggests we might be more comfortable with our experience of beauty, remarking that since we all succumb to it, ‘it would be well if we could recognise the meaning of our succumbing as a valuable response, an opportunity for self-revelation rather than a defeat.’ Given our positive response to a meaningful arrangement of temporary objects, let us dwell a little longer on why these things speak to us, even though they are not clever and satirical and politically charged. Perhaps Anna Karenina doesn’t speak to us because of the incisive political claims made by the main characters—perhaps it’s because of the humanity of the people portrayed, the similarity of their hopes to our own, and the impact of their historical situation on those hopes. We long to feel with each other, and in art, we can.

Delacroix (p. 66) felt keenly that too many artists were swayed by trends—the market, or popular opinion perhaps, or government demands. ‘A great number of talented artists had never done anything worthwhile because they surrounded themselves with a mass of prejudices, or had them thrust upon them by the fashion of the moment.’ I feel that while much art that is considered ‘classical’ and hence antagonistic to concepts in fact grows up around more slowly-unravelled concepts, perhaps this obsession with concept-above-all-else is the sort of fashion that we must brush aside and simply carry on working. We know that we are not subverting everything that has gone before, but we know that we are building on a meaningful history and connecting with people in inexplicable ways. And Delacroix (p. 43) urges us on:

You who know that there is always something new, show it to others in the things they have hitherto failed to appreciate. Make them feel they have never before heard the song of the nightingale, or been aware of the vastness of the sea—everything that their gross senses can perceive only when someone else takes the trouble to feel it for them. And do not let language trouble you. If you cultivate your soul it will find the means to express itself.

Chimero, Frank. 2012. The Shape of Design. (Self published).

Delacroix, Eugene. 2010 [1822-1863] The journal of Eugene Delacroix. Trans. Lucy Norton. Phaidon: London.

Poynor, Rick. 2006 ‘The beauty part.’ In Looking Closer Five: Critical writings on graphic design. Ed. Michael Bierut, William Drentel and Steven Heller. Allworth: New York.

Steiner, Wendy. 2001. Venus in exile: The rejection of beauty in 20th-Century art. University of Chicago: Chicago.