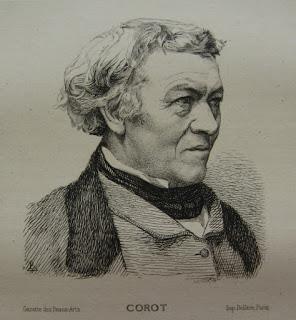

Félix Bracquemond, Corot

Félix Bracquemond, CorotEtching, 1861

Corot's own training was rooted in Neoclassicism. The aesthetic of his teachers Achille Etna Michallon and Jean-Victor Bertin links Corot to artists such as David and Ingres, Lorrain and Poussin, and explains the nymphs that tend to pop up in otherwise realistic landscapes by Corot, especially in his earlier phases. It was his discovery of the English landscapists J.M.W. Turner and John Constable that freed Corot from the tired formalities of Neoclassicism. Turner and Constable inspired both the Barbizon artists and the Impressionists - just not their own countrymen.

Camille Corot, Souvenir de Toscane

Etching, 1845

Delteil 1 (iv/iv), Melot 1 (iv/iv)

Besides his oil paintings and drawings, Camille Corot was also a printmaker, and in his printmaking practice he very nearly approaches Impressionism. He created 14 stunning etchings, of which I have a copy of the first, Souvenir de Toscane, dating from 1845. The magnificent freedom, the wildness, of this Italian landscape puts the viewer right on the spot, feeling the wind on your face. 1845 was the year Corot was hailed by Charles Baudelaire as the leader of "the modern school of landscape painting." This proto-Impressionist memory of Tuscany was the first etching Corot ever made. Twenty years later Félix Bracquemond found the unbitten plate in a box of nails, and convinced Corot to rework and print it. The first proofs were pulled in 1865, but it was not editioned until 1875.

Camille Corot, Souvenir de Basse-Bréau

Camille Corot, Souvenir de Basse-BréauCliché-verre, 1858

Delteil 73 (i/i), Melot 73 (i/i)

Corot also gleefully experimented with a new technique, the cliché-verre, invented by his friend Constant Dutilleux, Dutilleux's son-in-law Charles Desavary, the drawing professor Louis Grandguillaume, and Adalbert Cuvelier, an industrialist and paint manufacturer. By this means a drawing made on a prepared glass plate could be printed onto light-sensitive paper, very much in the manner of the "photogram" technique later invented by Max Ernst and Man Ray. Corot made 66 clichés-verre, and encouraged other Barbizon artists such as Daubigny, Millet, and Rousseau to try the technique too. He liked the freedom it gave to make images direct from nature that could then be printed back in the studio. Corot typically made only one or two prints from each cliché-verre, but many of the original plates survived in the collection of Eugène Cuvelier, and in 1921 Maurice le Garrec (successor of the gallerist Emond Sagot) published 15 of them in an edition of 150 copies in the portfolio Quarante clichés-verre. This also contained 16 plates by Charles-François Daubigny, 2 by Jean-François Millet, 2 by Théodore Rousseau, and 1 by Eugène Delacroix. One of Corot's plates has five subjects on one plate, hence there were really 36 rather than 40 clichés-verre in total. I am lucky to have acquired one of the Corots, Souvenir de Basse-Bréau, made in 1858.

Walter Sickert, The Boatman

Etching and aquatint after Camille Corot, 1890

Besides these original prints, Corot was happy for his work to be interpreted by other etchers. Some of those who made interpretative etchings after Corot are significant artists in their own right, such as Walter Sickert, Henri Guérard, Marcel Roux, and Félix Bracquemond. On a quick count, I have 19th-century etchings after Camille Corot by at least 30 artists, showing just how popular Corot's art became.

Étienne Gabriel Bocourt, Camille Corot

Étienne Gabriel Bocourt, Camille CorotEtching, 1882

Camille Corot himself seems to have been an equally popular figure. Often known affectionately as Père Corot, he was a hugely generous and encouraging man, confident in his own art but quite humble and modest in his attitude to it. I like his response to a friend who questioned him on his views on the afterlife. "Well, at any rate," Corot said, "I hope we shall go on painting up there."