Some of you know that I have an all-year pass to Masterclass, which means I can take any class I want without any restrictions. I’m also immediately informed when new classes are added. Over the last few years, I have taken several of these classes and enjoyed them a great deal. I say “have taken” but mostly, I watch the lesson videos and read the workbook. I haven’t decided yet to which one I’d like to fully commit, meaning doing the exercises and possibly submitting them and engage in a discussion with fellow writers. When you actively take the classes, you have the chance of receiving feedback from the teacher. This chance is especially high when a new class is uploaded.

Masterclass offers a wide range of classes for a very reasonable price. Some are writing classes, but not all of them. I’ll probably write another, more detailed post this month to tell you about some of the great content I discovered.

Last year, many new writing classes were uploaded, one of which was the courseReading and Writing Poetry by Billy Collins. Billy Collins was the poet laureate of the U.S. from 2001-2003 and the poet laureate of New York State from 2004 and 2006. I must admit, I wasn’t familiar with him but started the course out of curiosity and was immediately smitten. He’s such a lovely person and the way he teaches is very engaging and inspiring. You can see some of that in the intro I attached below.

In the course he reads many of his poems, explains the way he works, where to find inspiration. But he also talks about other poets and their work, since the course isn’t only about writing but also about reading poetry.

Discovering his poems was a joy. I like how so many of them have very mundane themes but with a surprising twist.

One of the poems he analyses is his ownElk Water Falls. Since this was my introduction to his poetry, I’m sharing it here.

Elk Water Falls

is where the Elk River falls

from a rocky and considerable height,

turning pale with trepidation at the lip

(it seemed from where I stood below)

before it is unbuckled from itself

and plummets, shredded, through the air

into the shadows of a frigid pool,

so calm around the edges, a place

for water to recover from the shock

of falling apart and coming back together

before it picks up its song again,

goes sliding around the massive rocks

and past some islands overgrown with weeds

then flattens out and slips around a bend

and continues on its winding course,

according to this camper’s guide,

then joins the Clearwater at its northern fork,

which must in time find the sea

where this and every other stream

mistakes the monster for itself,

sings its name one final time

then feels the sudden sting of salt.

Another one he speaks of in the course is this:

The Lanyard

The other day I was ricocheting slowly off the blue walls of this room, moving as if underwater from typewriter to piano, from bookshelf to an envelope lying on the floor, when I found myself in the L section of the dictionary where my eyes fell upon the word lanyard. No cookie nibbled by a French novelist could send one into the past more suddenly— a past where I sat at a workbench at a camp by a deep Adirondack lake learning how to braid long thin plastic strips into a lanyard, a gift for my mother. I had never seen anyone use a lanyard or wear one, if that’s what you did with them, but that did not keep me from crossing strand over strand again and again until I had made a boxy red and white lanyard for my mother. She gave me life and milk from her breasts, and I gave her a lanyard. She nursed me in many a sick room, lifted spoons of medicine to my lips, laid cold face-cloths on my forehead, and then led me out into the airy light and taught me to walk and swim, and I, in turn, presented her with a lanyard. Here are thousands of meals, she said, and here is clothing and a good education. And here is your lanyard, I replied, which I made with a little help from a counselor. Here is a breathing body and a beating heart, strong legs, bones and teeth, and two clear eyes to read the world, she whispered, and here, I said, is the lanyard I made at camp. And here, I wish to say to her now, is a smaller gift—not the worn truth that you can never repay your mother, but the rueful admission that when she took the two-tone lanyard from my hand, I was as sure as a boy could be that this useless, worthless thing I wove out of boredom would be enough to make us even.

And here’s another one I like a lot:

Central Park

It’s hard to describe how that day in the park

was altered when I stopped to read

an official sign I came across near the great carousel,

my lips moving silently like the lips of Saint Ambrose.As the carousel turned in the background,

all pinions and mirrors and the heads of horses

rising to the steam-blown notes of a calliope,

I was learning how the huge thing

was first designed to be powered

by a blind mule, as it turned out,

strapped to the oar of a wheel in an earthen

room directly below the merry turning of the carousel.The sky did not darken with this news

nor did a general silence fall on the strollers

or the ball players on the green fields.

No one even paused to look my way,

though I must have looked terrible

as I stood there filling with sympathy

not so much for the harnessed beast

tediously making its rounds,

but instead of the blind mule within me

always circling in the dark —

the mule who makes me turn when my name is called

or causes me to nod with a wooden gaze

or sit doing nothing on a bench in the shape of a swan.Somewhere, there must still be a door

to that underground room,

the lock rusted shut, the iron key misplaced,

last year’s leaves piled up against the sill,

and inside, a trance of straw on the floor,

a whiff of manure, and maybe a forgotten bit

or a bridle hanging from a hook in the dark.Poor blind beast, I sang softly as I left the park.

poor blind me, poor blind earth turning blindly on its side.

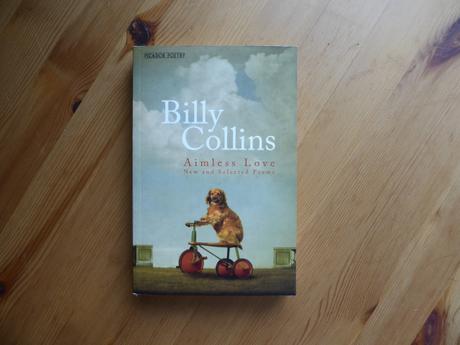

The Billy Collins collection I’ve got, Aimless Love – New and Selected Poems contains poems taken from four collections and about fifty new ones. All the poems I quoted here, can be found in Aimless Love.

I like the narrative quality of his poetry and that he takes something very mundane for his beginnings and then often moves to a bigger thought. The poem A Boy Shooting at a Statue is an excellent example for this.

Boy Shootig at a Statue

It was late afternoon,

the beginning of winter, a light snow,

and I was the only one in the small park

to witness the lone boy running

in circles around the base of a bronze statue.

I could not read the carved name

of the statesman who loomed above,

one hand on his cold hip,

but as the boy ran, head down

he would point a finger at the statue

and pull an imaginary trigger

imitating the sounds of rapid gunfire.

Evening thickened, the mercury sank,

but the boy kept running in the circle

of his footprints in the snow

shooting blindly into the air.

History will never find a way to end,

I thought, as I left the park by the north gate

and walked slowly home

returning to the station of my desk

where the sheets of paper I wrote on

were like pieces of glass

through which I could see

hundreds of dark birds circling in the sky below.

Maybe, unlike me, you already knew Billy Collins. If not, I hope I made you discover a new poet that you will like as much as I did. And maybe you’re even tempted to take his Masterclass.