Book review by Chris Hopkins.

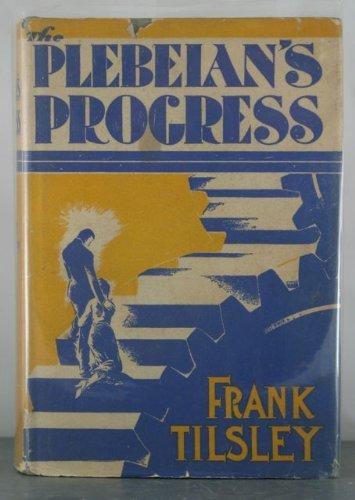

Dust-wrapper of the US edition, published by Covici Friede in 1933 – it’s metaphoric image shows Allen and Jane being carried towards their destruction by the cogs of industrial capitalism (I have been unable to find an image of the first British edition)

Dust-wrapper of the US edition, published by Covici Friede in 1933 – it’s metaphoric image shows Allen and Jane being carried towards their destruction by the cogs of industrial capitalism (I have been unable to find an image of the first British edition)

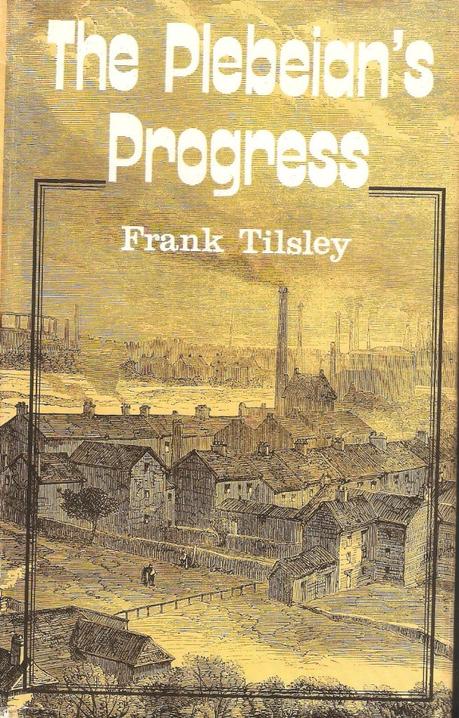

This is the Severn House 1976 reprint edition which I read. It uses an unidentified image of nineteenth-century Manchester, with its mills and chimneys.

This is the Severn House 1976 reprint edition which I read. It uses an unidentified image of nineteenth-century Manchester, with its mills and chimneys.

This is a novel about the representative (though as we shall see not all reviewers were convinced about that) lives of Allen and Jane Barclay, starting in Manchester before the First World War, but then mainly set in the twenties and thirties. They both come from very poor circumstances, but make great efforts to progress, and Allen becomes a reliable clerk. When things are good and Allen is earning £5 a week, they even manage to rent a decent house and buy some furniture, which gives them great and shared satisfaction. Allen is ‘let go’ when the small family firm he works for runs into trouble as the economy declines. He is forced to borrow money to pay the rent, and then steals money from his next employer to tide himself and Jane over, leading eventually to discovery and dismissal. He tries selling door-to-door (several different products), but completely fails to make a living (like many of the other door-to-door salesmen he meets). His last-ditch attempt to make money as a shoe-shine is equally a failure.

At this point, Jane has a miscarriage and never really gets over this. They move into a very poor single room and they begin to starve, as there are simply are no jobs in Manchester in the early thirties. Eventually, they become desperate, and Allen kills Jane to end it all, and is sentenced to death for her murder and hanged – the end which by this point he wants. The structure of the novel is based broadly on the eight scenes of Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (1732-34, engraved 1734, published as prints 1735). However, unlike Hogarth’s anti-hero Tom Rakewell, Allen inherits nothing and is born into debt and poverty. He does do things which are wrong and are petty crimes, but he feels he has little choice and no alternatives. Tilsley’s narrative is in this sense consciously different from Hogarth’s morality tale; like Greenwood’s Love on the Dole the novel shows that you need some economic security to make conventionally moral or even sensible choices. While Tom Rakewell ends his life in Bedlam, Allen ends his life on the gallows in Strangeways Prison. The final page gives something of the bitter texture of Tilsley’s story, setting the inner story of a life which the reader has followed for nearly three hundred pages against the indifferent ‘larger perspectives’ of newspapers and politicians which do not register that individual experience of life at all:

Newsboy called ‘Lunch Edition’ and displayed the contents bills of the two evening papers: ‘Viscount Snowden sees the King’ and ‘Manchester Wife Murderer Executed’. The Snowden poster survived the later editions.

In one paper, at the bottom of a page flaunting the headlines ‘No danger of Premature Return to the Gold Standard,’ was a short story under the placard caption.

‘ . . . Allen Barclay, who last September murdered his wife at their house in Agden Street and may be remembered as the third successive murderer to plead ‘Guilty’ at the last Manchester Assizes, was this morning executed in Strangeways Prison . . .

In the other paper a similar paragraph was sandwiched between an expensive double-column-spread advertisement, ‘Guinness is Good for You’, and the tail-end of a long interview with a famous statesman who was overcome with admiration at the magnificent way Britain had recovered from the crisis of the previous autumn … We had set an example to every country in the world, and could look forward to the future with the uttermost confidence. (pp 287-8)

The novel was generally positively reviewed, as it was for example by Richard King in the Tatler, even though he had what he saw as the misfortune to be sent the novel during a hot summer holiday season!

And all the novels I have read have been the kind of novels which go best with peace-under-a-tree, or pyjamas, and even less, worn at an open window. All except Mr. Frank Tilsley’s The Plebeian’s Progress‘ (Gollancz. 7s. 6d.), which, although a first novel apparently, deals with a sad reality of modern times, and deals with it sincerely, poignantly, convincingly, with little of the hesitation of a literary novice. A Common Tragedy. A pity, however, that the culminating disaster of Allen Barclay’s life tends to make it the tragedy of an isolated instance, and not, as it had been up to then, a typical misfortune of the modern world. However, this is easily forgiven, because the popular conception of tragedy is something dramatic and not the slow accumulation of gnawing little things which, alas is tragedy hardest of all to bear. Allen Barclay belonged to the poor. He was ambitious, however, and he was a worker. … Then came the Great Slump and his tragedy began . . . And so we follow him step by step into the abyss of poverty, bitterness, and heart break. The author, however, is himself seldom bitter. His understanding, in fact, makes this typical tragedy of a decent man’s downfall through no fault of his own extremely moving, without apportioning blame to anyone (28 June 1933, p.12).

I chose to read The Plebeian’s Progress partly because I knew that it was published in the same year as Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole, and that the two novels were compared at the time. Indeed, a review of the play version of Greenwood’s novel saw them as very close in style: ‘Love on the Dole and Frank Tilsey’s book might easily have been written by the same hand’ (unsigned column, ‘From Day to Day’, Nottingham Journal, 17 April, 1935, p.6.). Similarly, the critic Roger Pippett linked the two (as well as a German and an American novels) in his annual Daily Herald column on ‘Books of the Year’:

No best seller emerged from the scores of competent tales that were published, and the challenge of the crisis still went largely unanswered. Hans Fallada’s Little Man What Now and Catherine Brody’s Nobody Starves showed us how that challenge could be met—from the German and American angles. Both these books, which staged the cumulative effect of worklessness on men and women, achieved universal significance. Among our own authors Frank Tilsley and Walter Greenwood were almost alone in their attempt to exploit the social situation. The closing chapters of The Plebeian’s Progress saw Mr. Tilsley surrendering to melodrama, and I thought Mr. Greenwood’s Love on the Dole the better story—though both were sincere and disturbing efforts. (26 December, 1933, p.13).

Pippett clearly disliked the despairing murder and execution ending of Tilsely’s novel (an extremity which Richard King also saw in his review above as turning the novel’s focus from ‘a typical misfortune’ to ‘an isolated instance’). Greenwood’s novel and the subsequent play he co-wrote with Ronald Gow were frequently called ‘grim’, but The Plebeian’s Progress certainly takes grimness one step further, depicting lives which were not just distorted and impoverished but seen by one of the victims as not worth living at all.

At some stage, Frank Tilsley and Walter Greenwood got to know each other personally, for Tilsley wrote a piece for the Daily Herald in 1938 (12 July, p.8) about the Humanist Christening he had devised for his daughter after concluding that the Church was doing too little to oppose war and thus failing what he saw as the fundamental pacifism of the New Testament. Walter Greenwood was one of the godfathers in this ceremony – the other was James Lansdale Hobson – author of another depression novel, Harvest of the North, which was also adapted into a successful play (1934, 1935).

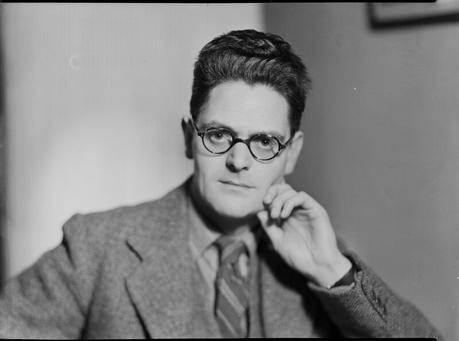

Tilsley (1904- 1957) went on to write a further eighteen books, the majority novels; he became a war reporter in the RAF during World War Two, and also worked for the BBC (see his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Tilsley ).

Frank Tilsley by Howard Coster; half-plate film negative; 1938; NPGx93213; copyright National Portrait Gallery and reproduced here with their kind permission under a Creative Commons Licence.

Frank Tilsley by Howard Coster; half-plate film negative; 1938; NPGx93213; copyright National Portrait Gallery and reproduced here with their kind permission under a Creative Commons Licence.