Global head of voice technology at Nodes, Maarten Lens-FitzGerald, takes us through the colourful history of voice tech and says we have nothing to fear. Sort of.

The first piece of voice technology was created by a hoaxer. In 1769, Wolfgang von Kempelen worked as a scientific advisor to the Empress of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Maria Theresa. Quite the overachiever, Wolfgang spoke eight languages, was a philosopher, lawyer, and self-taught engineer. He was also an inventor. And two of his strangest inventions changed the world forever.

That year, Empress Maria Theresa invited Wolfgang to a show. This was no ordinary performance. A French illusionist wowed the Viennese crowd with a series of baffling tricks and sleight of hand. After the show, the Empress asked her trusty advisor to explain how the tricks worked. Wolfgang broke each one down easily. The truth was, he hadn’t been impressed. He knew he could do better. On the spot, he made the Empress a promise to build a machine that would surpass anything they had seen that night. A true work of genius. Maria Theresa was intrigued and gave him six months to build it.

A royal hoax

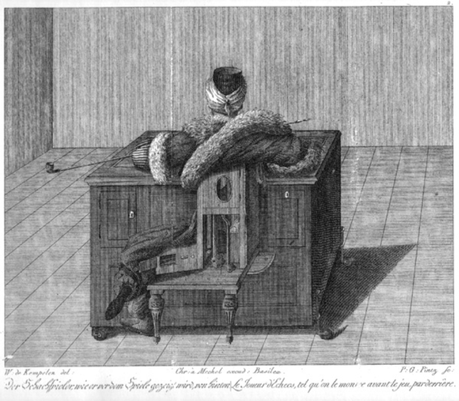

Wolfgang kept his word, and when the time came, he presented his invention. Footmen dressed in livery wheeled the contraption in, much to the surprise of the gathered royals. It looked like a wooden chest with a chessboard mounted on top. Attached to it was a human figure dressed in a robe and turban: the 18th-century, European idea of an exotic conjurer. It came to be known as the Mechanical Turk. Von Kempelen claimed it could beat any human being at chess. A contender volunteered and placed his chair in front of the automaton. When the Mechanical Turk made its first move, there was uproar. Shrieks of disbelief filled the halls of the palace. No one had seen anything like it. When the game was over, the contender got up from his seat in shock. The machine had trounced him.

The Mechanical Turk was a sensation. It traveled the world going head-to-head with some of the era’s greatest minds, including Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon, a man with more than a passing knowledge of strategy. Napoleon tried to trick the machine by making an illegal move. It responded by extending an arm and sweeping all the pieces onto the floor. The crowd gasped. They played again. Napoleon lost. Nobody could figure it out.

It wasn’t until many years after Kempelen’s death that the secret was revealed. The explanation was simple, albeit anticlimactic. Using a system of mirrors, Kempelen had hidden a compartment inside the chest, where an accomplice sat, making all of the moves. Though the whole thing was a hoax, it raised pertinent questions about technology, and introduced the possibility that, perhaps one day, a real machine could outwit a human. It wasn’t until IBM’s Deep Blue many years later that it finally happened.

The second invention

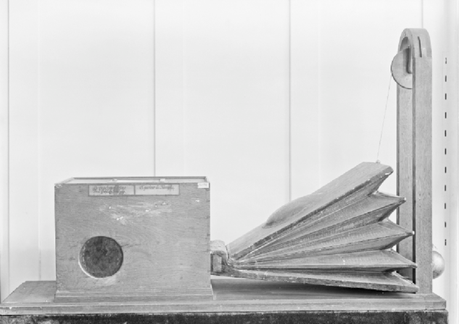

His second invention was not as outrageous. In fact, it was downright ridiculous. But Kempelen was devoted to it. He spent years researching and building prototypes. Fascinated as he was by almost everything, he studied human anatomy in order to build the world’s first speaking machine. A contraption which could mimic the physical structure of the human vocal tract. The finished product is unimpressive. You can see a working replica on YouTube right now. It looks like a pair of bellows jammed into a wooden birdhouse. By manipulating the bellows, and a reed in the wooden box, you can get the thing to speak. A few years earlier, a German-Danish scientist called Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein had built a similar contraption which could recreate vowel sounds. But Kempelen’s machine was different. He added elements that mimicked the function of the lips and tongue, allowing for consonants. The resulting voice sounds like a mix between a crying baby and a duck call. It’s absurd, disturbing, and eerily human.

Though Klempen’s speaking machine was nowhere near as provocative as the Mechanical Turk, the two had much in common. Both strove to recreate something vitally human. In the case of the speaking machine, the most impactful – and most human – technological advance in our history: speech.

“We humans have been talking for 50,000 years. It’s part of what makes us human and part of why we build amazing things.” Maarten Lens-Fitzgerald is what you might call a voice technology advocate. He’s also the global head of voice technology at Nodes. So, his enthusiasm for the subject is understandable. “If you think about computers and technology, conversation is the key to everything.”

Though we humans have been chatting to each other for 50 millennia, Maarten agrees that Klempen’s crude speech machine was one of the first real attempts at working voice technology. The next significant step, however, would not come for almost two hundred years.

The big leap

“The first machines,” says Maarten, “were made in the 50s and 60s.” He’s referring to, amongst others, the pattern playback device designed by Dr Franklin S. Cooper, which could read visual patterns representing the sound of a voice, and recreate them in audio. The voice sounds much as you might imagine: tinny, robotic, and creepy. A far cry from the voice technology of today.

“The voice as we know it today was born with Siri 12 years ago. That was the big leap,” says Maarten. “It was made by Dag Kittlaus and his partners. When they came up with this platform – which they launched as an app – Apple bought it within several months. Steve Jobs literally invited them to his house and the deal was done pretty quickly.” The story of Siri’s acquisition is remarkable. The type of deal young Silicon Valley developers dream about. Kittlaus, a 34-year-old Norwegian, and former executive at Motorola, sold Siri to Apple for a rumoured $200 million. An astronomical amount. Jobs invited Kittlaus to join the Apple team and help develop the software. The two of them worked together until Jobs died the day after Siri launched. “One of the rumours is that Steve Jobs knew that this was the next evolution after mobile, and this was his last acquisition before he died. So, he rushed it through.”

As groundbreaking as Siri was, Apple failed to capitalise on its potential. “Unfortunately, the next CEO, Tim Cook, was very good at ERP (enterprise resource planning) but not at innovation,” says Maarten. “So, it got lower on the list of priorities.” This is a sentiment shared by some Apple employees. One stated that, since Jobs’s death, Apple was lacking “a big picture”. For a while, it seemed that Siri had lost its way. But Maarten remains optimistic. Despite its failing, he believes the platform is immensely important. “Even though it doesn’t always work the way we want it to, it’s still the biggest platform out there. And in all the languages, even Finnish!”

Voice goes corporate

The next big step in voice technology came when Amazon threw their hat in the ring. Their entrance surprised everyone. Sure, it made sense that Apple – a tech company, after all – would be interested in voice tech, but a retail company? That was new. “It was really random,” agrees Maarten. “They started five years ago with the smart speaker business. Nobody had ever done that. Now they have over a 100 million of these devices out there. They’ve been that successful.”

Amazon Echo Dot speakers sold out earlier this year. Successful, by any measure, but not the full story. They’ve also got over 150 Alexa-equipped products on sale. Plus, Alexa works on over 28,000 more. “They’re on their fourth generation of devices,” says Maarten. “Usage is up. They have the most skills of all the players out there.”

But who are the other key players? And how do they fit into the recent history of voice tech? “Four years ago, Google got on board with their resistance platform, and now Samsung is coming online with Bixby,” says Maarten. “Bixby is interesting, because the second version, which was announced in November, is made by the original Siri guys.”

That would include our old friend Dag Kittlaus, who, in 2016, presented Viv, their new intelligent personal assistant software, to the world. Viv comes from a Latin root, meaning, life. And Kittlaus claimed they were going to “breathe life into the inanimate objects of our life through conversation”. Poetic, but the true goal was to create the first all-purpose assistant capable of working across all devices. Many were interested, including Samsung. They acquired Viv for their Bixby platform and whipped out the chequebook, landing Kittlaus his second $200-million deal.

This enormous payout brings us, fittingly, to today’s landscape. Several mega-companies investing hundreds of millions of dollars in voice tech, as it slowly starts to proliferate all the devices around us. We’ve come a long way from Kempelen’s creepy duck-baby. Which begs the question: what next?

Emerging trends

“Why do we need to type and swipe and pinch when the computer can now talk?” This is the question that drives Maarten to do what he does. You’d be forgiven for assuming that he had some sort of background in linguistics. His real background is in technology. For years, he has delved into emerging tech, learning everything he can about it, then using his knowledge to spot trends and developments, and figure out how to use these to create value through communication.

“This is my fifth new medium,” he says. “My first was web in 1994, then email in 2001, mobile in 2006, and augmented reality in 2008. I had a very large company called Layar, which was an AR platform with 45 million global installs.” After a stint investigating the future of work, he found himself looking around for a new technological development to get excited about. Literally. “I was literally sitting at home thinking, ‘What should I do?’, when I saw my speaker. I was in the first Beta round for Amazon, and that was the only device I had at home that I was using daily, from the moment I got it.”

And it wasn’t just him. He got the whole family involved. “I have videos of my twin girls fighting over turning the lights on and off. So I was like, ‘You know what? I’m going to pick that up because I know it’s coming, and I have a sense for this.’” Whether or not this is a sixth sense remains to be seen, but Maarten’s track record suggests a spooky ability to predict trends. He’s adamant, however, that he is not a technological soothsayer. “I want to be an evangelist for this technology, I do that well.”

Spreading the word

When he took up voice tech, his initial idea was to create a business. “Two years ago, I started an event called Open Voice Series. I wrote newsletters and even made a podcast. Then Nodes came along, and I realised I didn’t necessarily want to build a business.” Instead, a different role presented itself. Maarten decided he wanted to introduce businesses to the technology and its potential, to spark a curiosity and an understanding about its uses and benefits. He’s good at it, too. A naturally warm and charismatic speaker, Maarten spends much of his day-to-day on missionary work.

He describes a recent session with a large consultancy firm: “I was at their AI expert knowledge event and I did two introductory workshops on voice design, where 30 people in groups created their own voice service. I helped them design their first dialog ever. It was a really fun exercise. Then they tried it out on each other. It always fails. But this is how they learn. It isn’t easy to create natural dialog. If you accept that, you learn much faster.”

Maarten does a lot of stage work and workshops with companies, talking about practical ways they can implement voice tech. The end goal is always the customer. But dealing with customers means dealing with data. Personal, sensitive data. Which raises some uncomfortable questions.

Privacy: paranoia or legitimate worry?

Are we right to be blindly optimistic about voice technology? Can it be appropriated for sinister means? Should we be paranoid? With recent events, we’d be forgiven for thinking our deepest fears are becoming reality. It’s natural to feel surveilled. After all, some of these platforms record and store voice commands. What the hell do companies like Google want with our voices? Are we in for more Cambridge Analytica shenanigans? Maarten insists there’s no reason to panic. Yet.

“There’s GDPR here in Europe, so they can’t do anything. Amazon and Google won’t do stupid stuff because they have too much to lose.”

“There’s GDPR here in Europe, so they can’t do anything. Amazon and Google won’t do stupid stuff because they have too much to lose. So even though there’s a fear, they won’t go full Cambridge Analytica. They know they’ll be shooting themselves in the foot.”

Reassuring words. But don’t get too comfortable. There’s a scenario you probably haven’t even thought of. “If I look deeper, there is one risk,” says Maarten, ominously. “After a few minutes of talking to someone, you get an idea of who they are, and you have a feel for how you should communicate with them to make them say certain things. A computer will be able to do that, too. The computer will understand how to get someone to say yes or no.” Sound terrifying? Wait, there’s more. “Say I miss my mom a lot. What if the voice talks like my mum? It might make me feel even more comfortable, so it’s easier for me to be manipulated. The raw data for my voice is like psychometric data. If you know my archetype, you know what gets me going and what doesn’t. So the computer can a better ROI if it mimics the things that are meaningful to me.”

Suppress, for the moment, the sound of your mother’s disembodied voice coming at you from a smart speaker in your house. The technology isn’t there yet. But that doesn’t mean it won’t be soon. And when it is, how do we avoid ending up in some sort of Black-Mirror nightmare? The answer, Maarten thinks, lies in legislation. “We need to create a legal framework to make sure that you and I are protected. This is the good thing about GDPR. These companies should delete our data; they shouldn’t be able to do whatever they want with our voice analysis. There’s a fine line between what the machine learning needs to make sure it works and manipulation.”

And where exactly is that line? “We don’t know! It’s not defined. But this is what I love to do, to figure out with the rest of the world where that line is and to make sure we stick to the right side of it.”

The barriers to ubiquity

Privacy concerns aside, there are three other obstacles impeding us from fully embracing voice tech. One of them is a technological barrier. There’s no getting away from it, for many years, voice tech has been crappy. Maarten agrees but isn’t fazed. Technologically speaking, we’ve hit a tipping point in machine learning. “Computers can discern and understand different types of images, and that algorithm works similarly for voice. This has accelerated everything. But it’s machine learning, so it needs input. If you take, for instance, voice tech in the Dutch language, it sucks. The databases are still too small. Not so in English. And companies are pouring more resources into it. Amazon has 10,000 people working on it, and Apple still has 2,000 working on it.”

The second obstacle is human. As children, many of us watched shows like Knight Rider, mesmerised by KITT the talking car. But though David Hasslehoff made it look cool, the reality of talking to a computer is a lot more banal. And awkward. Even after years of familiarity with software like Siri, it’s tricky not to feel dumb when you’re in the street asking your phone to help you buy toilet paper. Maarten agrees. “Just yesterday, I walked into a store with my ear buds and I sheepishly said, “Hey, Siri, pause.” And the sales guy laughed at me. But with this kind of thing, I love looking back in time. I have a Dutch video where I interviewed people in the street and asked them whether they thought they would be shopping using voice tech soon. And they were all like, ‘No way! Screw that!’ And then I cut away to a video from 1998 where people in Amsterdam were interviewed about mobile, and they said things like ‘No! I already have a phone, I’ll just stop at a bar and use the phone there!’ Things will change. And I think that in five to ten years, it will be normal.”

The third obstacle has a lot to do with age. “My parents got an ATM card in the mid-eighties. It took them ten years to trust getting money from an ATM. Now, a lot of people are scared to have a speaker in their house. They needs to make space to accept that in their lives. Young people will do this quicker, and older people will be sceptical. Actually, the people in their 30s and 40s are the most resistant.”

“Gradually, the more people use it, the more the machine will learn, and the further it will expand. In the end, the thing that will mostly hold us back is legal. The laws have not kept up with developments like Google Duplex, which can call a restaurant and make a reservation in your name. It’s understandable that people ask: How do we deal with this? What if it’s a robocall? There’s lots of stuff that legal people will identify as a risk, especially in Europe, which is a tough market for a Google-like company. But it will happen.”

The human touch

We all know Google wants to collect data, Amazon wants to make money, but what about the more humanistic uses for voice tech? Maarten thinks that, these days, commercial and humanistic concerns go hand in hand. “Just switching on my lights or turning on my vacuum cleaner is, in a way, humanistic to me. It makes my life easier. It’s the ultimate customer-centric channel. It’s not like mobile. where you open your phone and end up getting so distracted that you forget what you originally wanted to do. It’s the cleanest way to communicate, so companies using it are forced to be more customer-focused. And if they’re not, they’re gone. And that is the humanistic angle, because it’s not about them, it’s about us.”

If we think back to Wolgang von Kempelen, we realize that it was always about us. Yes, we like technology because it makes our lives easier and more convenient. But there’s something else at play. Something profound. A question about what it means to be human.

Both of his inventions were built to satisfy a deep curiosity about who we are. A mysterious force impels us to replicate the very things that make us human, to look into the eyes of an automaton and see ourselves; to hear something, a word, a recognisable phrase, in a voice that sounds like ours. Maarten truly believes that, whether you embrace it or stubbornly resist it, voice technology is here to stay. And it’s going to start playing a bigger role in our lives. That voice that sounds like us – we’re going to be hearing a lot more of it: “Any company, in the next five years, much in the way they have a website, or an app, will have a voice service. The way you and I talk every day, that’s how we want to be able to talk with anything.”

Indlægget The past, present, and future of voice technology And why we’ll all be using it in five years blev først udgivet på Nodes UK.