Thus far in his slim corpus, each Terrence Malick film has solidified and purified Malick’s transcendentalist belief in the connection of man and nature, even when he shows horrible, destructive acts. The murder spree in Badlands fits with uncomfortable harmony with the flat plains and scattered, gnarled grass lining the sides of Midwestern country roads. Days of Heaven moved deeper into that territory to bask in the glow of our amber waves of grain, yet the mangled love triangle and plot to steal the farmer’s wealth contrasts to the invasion of locusts naturally laying waste to the area. The Thin Red Line builds further on this contrast, presenting even the monstrous environmental and human cost of war as an exaggerated of the destruction inherent in an ecosystem even as it pushed gently and spiritually for an end to such horrors.

Thus far in his slim corpus, each Terrence Malick film has solidified and purified Malick’s transcendentalist belief in the connection of man and nature, even when he shows horrible, destructive acts. The murder spree in Badlands fits with uncomfortable harmony with the flat plains and scattered, gnarled grass lining the sides of Midwestern country roads. Days of Heaven moved deeper into that territory to bask in the glow of our amber waves of grain, yet the mangled love triangle and plot to steal the farmer’s wealth contrasts to the invasion of locusts naturally laying waste to the area. The Thin Red Line builds further on this contrast, presenting even the monstrous environmental and human cost of war as an exaggerated of the destruction inherent in an ecosystem even as it pushed gently and spiritually for an end to such horrors.Malick’s films, like Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poetry, make me want to walk in a field, palms outstretched, letting leaves and blades of foliage brush against my fingertips. When I experience their work, I feel that I can go outside and be jolted by the current running through nature, running through us as well if we’d stop breaking the circuit. Their conceptions of the universe are heady, allegorical and concerned less with what’s before their transparent eyeball than its spiritual essence (even the romance between Smith and Pocahontas feels like an encapsulation of the pure love of nature for those who can tap into its grace). Yet they also are some of the most tactile artists to ever live, offering intoxicating panoramas of nature and the past, present and future it contains. Unlike Emerson, however, Malick lacks the self-absorbed narrow-mindedness that undercuts his own idealism. Malick seeks to capture it all, even when he leaves out one side entirely (as he did in The Thin Red Line). His view of destruction as but one facet within nature is but one example of his more universal belief in the force that connects us.

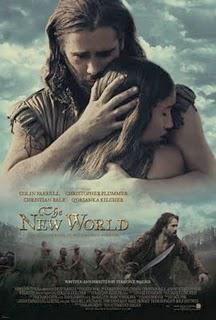

That Malick would make a film about Native Americans seems so obvious it’s a wonder he didn’t find the inspiration to do it about 30 years before he released The New World in 2005. Perhaps it was for the best, though: by building off the moral, philosophical and natural themes he’d refined to that point, Malick crafted unquestionably the most singular film to chart the English settlement of America and the interaction with the tribes already there. It is not about environmentally indifferent white settler vs. the attuned native, though certainly conflict and discrepancies exist, as do moments of horrific violence that destroy so much that nature csually covers over in a season. Nor is it a Disneyfied version of John Smith’s romance with Pocahontas, a symbolic union of an open-minded Englishman bonding with a purer spirit, though elements of that exist as well.

What The New World is instead is an attempt to come to grips with the awesome power of a new, seemingly limitless region. Relative to the Europeans, the Americas may as well have been a new world entirely, a place totally unaffected by the influence of the world as it was known. Likewise, the Native Americans come into contact with a new people with a wholly different cultural perspective and social ethos (not to mention virulent diseases).

After all, the first shots of wonder belong not to the Englishmen, who view land with a combination of dehydrated delirium and relief, but the Indians, who regard the great ships drifting to coast with stunned curiosity and awed apprehension. The settlers disembark and immediately set about building camp, scarcely stopping to take in their surroundings, the sound of the first felled tree echoing in a nearby field teeming with inspecting Powhatan warriors like the dying screams of a fallen comrade. Only John Smith (Colin Farrell), a mutineer brought to shore in shackles and freed under probation, explores this uncharted land with reverence.

Smith innately understands the future of America, sensing in its vastness the principles of democracy and republicanism that will take root in its fertile soil. As his comrades back at the rudimentary Jamestown squabble over rank and class, Smith finds himself sent to negotiate with the Powhatan king against protests over his low social status, which morphs into tacit enthusiasm as the men consider the likelihood of the natives not pummeling him with a club. Ironically, it is because of their caste system that Smith finds himself thrust into the nature he loves, where he can ruminate “Here the blessings of the earth are beloved by all.” Later, however, Smith comes into some authority, and he immediately imposes dictatorial control over Jamestown when it looks as if he might help the ailing settlement incorporate with the Indians. Malick’s universality flirts with the political here, laying out not only the ideological foundation of America but the contradictions in its actions.

Nevertheless, this preemptive insight into America’s political future factors into the structure of the film, which democratizes the image as much as Godard’s Marxist camera in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her. This is especially true of the extended edition released on DVD and Blu-Ray, surpassing even the original “Italian” cut of the film before Malick trimmed it for “commercial” considerations, relatively speaking. That film was poetic to its core, but this longer cut breaks up the stricter focus on Pocahontas (Q'orianka Kilcher, in a mesmerizing performance that should have translated into a much busier career than it did_ to allow for greater contributions from all its players, not just Smith and Rolfe but supporting figures who drift through Malick’s more ambient tone poem like vague trills, ever quite themes or motifs but always distinctive.

The narration too shifts, moving off more identifying visual accompaniment to borderline free-associative impressionistic collage of sight and sound. It’s never difficult to tell who’s speaking, but the images often move entirely out of the perspective of the narrator into that of another character (or characters), moving beyond even a vaguely political aesthetic into a deeper, more spiritual connection linking everyone.*

That is not to say that the film presents a trite, hippie “We’re all the same deep down” message. Malick, for all his poetic abstraction, has always had a realistic side, and he plainly delineates the two cultures through their interactions with each other. When the Englishmen set down on land, one of Capt. Newport’s (Christopher Plummer) first order is to level trees in the surrounding area to build a fort and to ensure clear vision against any attackers, already exploiting the land for gain. Smith’s time with the Powhatan, learning their customs, their social interactions and their innocence, becomes all the more stunning when he returns to Jamestown and his blissful time with the Indians is thrown in sharp relief against the misery, backstabbing and animalistic savagery within the starving colony.

What Malick finds, however, is a spiritual link binding all these players to each other, as well as to nature. The longer cut contains more microscopic gestures between characters, tiny mirror movements that close circuits to let the current flowing through everything pass between them. Even by Malick’s standards, The New World is a film comprising almost nothing but grace notes, interspersing playful interaction, aching rumination and pillow shots of trees and rivers into each segment until distinguishing between them becomes futile. The narrative takes on a sort of shared consciousness, an impressionistic voyage that ultimately reveals an objective truth about us, an objective truth no one can articulate, not even in Malick’s flagrantly literary internal speech.

Framing that objective connection are the ubiquitous shots placed at such a low-angle that cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki practically has to aim the camera straight up to capture any action. This only exacerbates the film’s unabashedly spiritual and religious nature: some of its first shots are of characters looking up to the sky, Pocahontas beckoning to the cosmos with open arms and Smith, hands shackled in forced penitence, gasping up at rain dripping through his hot brig cell on the ship. Sunlight beams down on these characters, illuminating their attempts at sovereignty and collaboration, and smoke and fog always obscure the more violent battles and atrocities like Adam and Eve trying to hide their sins from the Lord. What Malick seems to be suggesting, however, is not the connection of the Indians and/or the Englishmen to God but that humanity is God.

Malick sets all of his films in the past; his most “recent” pictures take place in or after the WWII era. But all of these films feel current, and temporal states often seem beside the point in Malick’s work. This transcends Emerson’s, well, transcendentalism for omniscience, albeit gained through unification and oneness with the world. The aforementioned hints of politics in Smith’s internal monologues and the film’s structure cast Smith as both the symbol of arriving British colonists and for the future revolutionaries who will make a new nation of these settlements. He experiences the present but represents the future, though his actions and thoughts tie him to that distant time so closely that the split becomes less contrast than contrapuntal. The New World may, even judging from its title, concern immersion in the unfamiliar, but it demonstrates how every person has the whole of Earth’s history and future coded into intermittently and involuntarily accessible places within us.**

A common misconception concerning Malick’s films posits that they juxtapose man with nature. Both The Thin Red Line and this film show warfare, while Badlands and Days of Heaven use their Midwestern amber waves as backdrops to killing sprees and intrigue, respectively. However, Malick positions the brutal actions of humanity as a part, however exaggerated and senseless, of the turbulence inherent in nature. Note the preference of ambient noise over scored music in the extended cut and how natural sound nevertheless proves an adequate soundtrack: when Smith loses his Powhatan guide to the chief early in the film, his on-guard wandering through an overgrown field is punctuated by the shrill buzz of crickets, a natural glissando ratcheting up tension. Nature herself starves out the Englishmen, who only truly set upon themselves and the natives when hunger drives them to desperation.

Everything has its contradictions, which is why The New World is so hard to pin down: it captures so much (too much, for some) of the messiness of life. Charting Pocahontas’ evolution from cherubic, mystical savior through romance and diplomacy and ostracism and, finally, comfortable life as the toast of the English court is interpretive and realistic, a fitting split for a film that combines painstaking historical accuracy with outright myth.

“That fort is not the world,” Smith says at one point, subtly critiquing the Western bent even of films sympathetic to the Indians at the centuries of hardships they would soon endure. It’s a lesson Smith—and, later, Rolfe—forgets, seeking to bask in Pocahontas’ unique energy even as he molds her into someone he can make his own. This is more true of Rolfe than Smith, who does try his best not to let the other Englishmen “contaminate” her with their base, simple needs in their starved madness, but both men see her spiritual power through Western lenses. Each sees in her a chance for a new start: Smith sees her as the path to becoming a new, good man after his pirating days, while Rolfe views her as the only means to heal his broken heart from his English wife's death. Their desires for individual new lives, of course, serve as a microcosm for the second chance America represented to those who could brave the voyage; in that sense, tying together colonial idealism with the romantic longing between the two Johns and Pocahontas is not only artistically valid but logical.

Pocahontas herself learns Smith’s message when she eventually goes to England with John Rolfe (Christian Bale), arriving in an Old World that’s new to her. Malick thus expands on his view in a cyclical fashion, returning to the same shots and motifs with different players, altering the meaning. Reflections of actions, ideas, even of nature mirrored in the waters of the Virginian swampland visually prefigure the cycle of birth, death, separation, reconciliation and exploration that gyrate through the film. The director even subverts visual expectation by not only beginning on a ship arriving but ending on it too, even if the former accompanies birth imagery and the latter death knells. Additionally, ending with another arrival suggests that the story is not done, that a new iteration of the cycle will begin with new players, using our modern awareness of the repeated atrocities of colonial and native exchanges to fill our imaginations as to the outcome. However, if this film is so rooted in what came before, not only in terms of its cyclical movement but in the context of all cinematic depictions of colonialists meeting and battling Native Americans, how is it that everything in it feels as if it’s being viewed for the first time?

This extended cut, adding 22 minutes to the debut Italian cut and nearly 40 to the theatrical version, pushes the film over that hump separating it from loose-narrative romance into the purest embodiment of Malick’s Emersonian ethos, as well as the best response to the ethnocentrism within Emerson’s and Whitman’s supposedly universal view, never shying away from the contradictions in Smith’s ultimately trite interpretation of the magnificent world around him. By incorporating more of the characters and finding the right balance between human and nature (which is not to say that they are evenly split, only that we get a better sense of place within this gorgeous and intimidating world), Malick finds a more holistic view of our connection to nature and the history and future each of us carries inside.

I do not mean to say that the extended cut is “better” than the theatrical: both have their strengths. I find in the theatrical cut a certain thrumming force that vibrates to my frequency and lapses me into a trance. But I have a better idea of what’s being communicated in this longer cut without being sucked out of the experience of Malick’s film, and in fact I feel more connected to its pulses than I was before, more able to get my bearings inside its hypnotic flow and see where I’m going instead of being swept along. I shall be interested to revisit the theatrical version to see just how much the elongated shots and deeper levels of personal interaction alter the meanings, to see nature confounding these people, even those stereotypically placed at one with it. Malick can get seemingly infinite mileage out of this film, his tweaks opening up whole new connections and altering entire perceptions.

One of the tattoos on Smith’s body says “Carpe Diem,” which may be the simple moral at the heart of this story. When the characters surrender not only to the power of nature but of each other, they become one with the present and experience life in all its beautiful chaos. Death is always the least poetic aspect of a Terrence Malick film, a tragically blunt act that disconnects that figure from the force tethering all flora and fauna and leaving those alive to reel at the shockwaves. (This supports the idea that Malick frames his religious reaches around a God of man and nature and not a conventional Judeo-Christian reading). The New World, a film set 400 years in the past, resides more firmly in the present than just about any film I can name,*** and if it hits dead-ends at times and has to reverse out of them, isn’t that a byproduct of living in the moment and following the flow wherever it leads?

*And by filtering its semi-idealized aesthetic through the innocent eroticism of Pocahontas’ mesmerizing effect on all those around her, Malick recalls Whitman as much as Emerson.

**Though I’ve resolutely avoided as much Tree of Life chatter as possible, that film appears to expand on this point even further, moving beyond the planetary scope of this film into the universal.

***Edward Yang’s Yi Yi is all that comes to mind; it too works with a cyclical intimate epic of life and death.