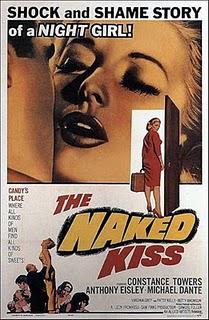

After working in the studio system throughout the 50s and scoring a few hits along the way, Samuel Fuller realized his interests and methods were becoming increasingly incompatible with the conservative, audience-wary executives and elected to align his independent style of filmmaking with an independent style of financing. Together with Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss marked Fuller's move to small-scale studios and microscopic budgets. Fuller's films always looked as if he made them without much money, but he at least had a pick of some well-known stars and could make a color film or two. Now, he was back to black-and-white and unknowns.

After working in the studio system throughout the 50s and scoring a few hits along the way, Samuel Fuller realized his interests and methods were becoming increasingly incompatible with the conservative, audience-wary executives and elected to align his independent style of filmmaking with an independent style of financing. Together with Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss marked Fuller's move to small-scale studios and microscopic budgets. Fuller's films always looked as if he made them without much money, but he at least had a pick of some well-known stars and could make a color film or two. Now, he was back to black-and-white and unknowns.Necessity, though, is the mother of invention, and the stylistic choices Fuller made to sidestep the budget shortcomings led to some of the most impressive direction of his career. A combination of Sirkian melodrama and lascivious noir, The Naked Kiss contains sequences wholly removed from the pulpy realism of the director's early work, even as it still bears his instantly identifiable stamp.

The Naked Kiss opens in a bewildering sequence that alternates POV close-ups with third-person medium shots in a frenzy. We don't even know who these characters are, what they do or why the woman is beating the man with her shoe. When the man grabs her hair and yanks, it all comes off, revealing her to be completely bald. Damn it, Sam, it was weird enough as it was. The woman beats the drunkard unconscious and takes out a wad of cash from his pocket, only keeping "the $75 I got comin' to me." She grabs her wig, straightens it out and the frame freezes to throw up the title. Who the hell couldn't love Sam Fuller?

When the action resumes, we follow the woman, Kelly (Constance Towers) to a small town called Grantville as she leaves the city looking to start over. The local sheriff, Griff, spots her and seems to know her true profession before she says a word, though she plays at being a traveling champagne saleswoman. Griff knows the deal: buy the champagne for $10, and for another $10 you can have the dame to go with it. He takes Kelly back to his place and enjoys her services, then informs her to take her business across state lines. "“If I let you set up shop in this neighborhood," he says, "the people would chop me like a ripe banana.” Griff recommends she get a gig at a bordello across the river disguised as a farcical candy shop. Why, he can even put the good word in, as he's a friend of the madam, Candy, and, it seems, a frequent guest.

Disgusted by the rank hypocrisy and looking for a change of pace anyway, Kelly decides to stay in town and get work as a nurse's aid at a children's hospital caring for handicapped kids. I suppose Fuller had to go out of his way to out-blunt the overused and unsubtle Madonna/whore dichotomy. As we learn late in the film, Kelly cannot have children of her own, and Fuller peppers the film with clear indications of her maternal desire, from the baby carriage visibly in the lower third of the screen as Griff pulls her aside in a park in their first meeting to the smiling faces of the crutch-ridden children who look to her for help and support. She proves a fine nurse, and the head of the ward, Mac (Patsy Kelly, who speaks as if, with every line, she considered using a Scottish accent but said "fuck it" halfway through) sings her praises to Griff, who can barely contain his fury. He accuses Kelly of using the hospital as a front, but she insists she's making a change.

Fuller's wit runs through the film: when Kelly finds a place to live, the landlady tours her through the room and proudly shows of the bed, which Kelly admires. "Do you realize we spend about a third of our lives in bed?" the old woman asks innocently, and the smile freezes on Kelly's face as a light sigh hisses out of her. The landlady also has a creepy, headless dresser's dummy upon which she has fastened a shrine to her late suitor Charlie, who died in WWII and never came home to marry her (the helmet on top of the mannequin has the insignia of the Big Red One on it, the division in which Fuller served). The woman kindly offers to take the thing out of the room, presumably to prevent horrible nightmares, but Kelly doesn't mind and jokes that she'll have someone to talk to. The landlady says that Charlie will always agree with her, with a chuckle that conveys a cracked madness.

Eventually, Kelly finds herself in the mansion of the man who gave the town its namesake, J.L. Grant (Michael Dante). When she arrives, he's returned from Europe and brings gifts for all his friends. Though he did not know of Kelly being invited, Grant has a spare for her, a trinket from Venice, which lights up her eyes. Grant looks like a vampiric Garry Shandling, and his spacious, ornate home feels drafty and frigid. He takes a shine to Kelly, his flattery conveying a predatory mood. "Intellect is seldom a feature of physical beauty," he says when Kelly mentions Byron, "and that makes you a remarkable woman."

Fuller moves between cynicism and unabashed sentimentality so rapidly that the two bleed into each other without clear separation. At the hospital, Kelly can be stern with the children to make them do their exercises, but we also get to see her ad-libbing a story about the children learning to walk again, leading to a dreamlike sequence showing the kids running outside without crutches or braces. Kelly's courtship with Grant is even more stylized: Grant shows Kelly silent video from Venice, and the sofa on which they sit slowly sinks into an abyss surrounded by infinite black as the setting switches back and forth from the Venice seen in the film reels and the sofa. To enhance the mood further, falling leaves drift into both places. These dips into full on cinematic expression show Fuller fully embracing his skills. He even inserts some self-reflexivity: playing at the theater when Kelly rides into town is Shock Corridor, and the book she reads is Fuller's own pulp novel The Black Page.

The more daring aesthetic informs the greater effrontery of the narrative. By this point, Fuller had put his deliberately unsubtle, aggressive writing to issues of American imperialism, racism, Communism and more. Here, he travels into the seedy underbelly of quaint small-town life, predating David Lynch by nearly two decades. Buff, another nurse in the children's ward and Griff's unofficial child after she lost her father in Korea, can no longer bear the sight of kids struggling and considers working as a Bonbon. Candy even gave her a loan as a sort-of default payment. Kelly literally slaps some sense into the girl, who defiantly says she can make major money at the shop. “You’ll hate yourself," Kelly intones, as much to the audience as Buff, "because you’ll become a social problem, a medical problem, a mental problem, and a despicable failure as a woman.” Afterward, Kelly takes the $25 Candy used to buy Buff and shoves it in the madam's mouth. It takes a prostitute to take down another, apparently, as Griff certainly isn't rallying troopers across state lines to bust the place.

And Griff's hypocrisy at the start is nothing compared to the truth behind Grant: Kelly returns to his mansion to show him the wedding dress she bought for their wedding, only to find him with a little girl. Fuller avoids displaying anything lascivious but makes the intent all too clear. Grant collapses at Kelly's feet, begging her to marry him. "You understand my sickness. You've been conditioned to people like me," he says with wild eyes. But not even the prostitute can stomach this, and Kelly grabs a phone receiver and strikes Grant dead. Instantly, the world collapses around her as Griff assembles old enemies from Kelly's dirty past and a vengeful Candy brings in all new foes to keep her in jail.

Though it does not attain the same fever pitch as Shock Corridor's maniacal build-up, the climax of The Naked Kiss brings out the fury of Fuller's aesthetic and writing. The man Kelly beat at the start returns and is revealed to be her pimp and the man who shaved her head, but Griff accepts his excuse that she stole from him. Candy breaks Buff into lying about Kelly's attempt to help her and finds a few more character assassins. Fuller clarifies an earlier moment of hesitation that crossed Kelly's face when Grant kissed her and also explains why he chose his title: Grant gave her "the naked kiss," the sort of liplock that communicates when a man is a pervert. She recognized it instantly but still allowed herself to hope, to aim for the idyllic lifestyle she sees around her despite the ironies piling up before the audience.

Even when Griff finally sees reason and finds the girl who can exonerate Kelly, Fuller does not relent. Griff, having bought Kelly's explanation when Buff later confesses in private, urges Kelly to coax an alibi from the scared girl, even to manipulate the child. At last exonerated, Kelly emerges to find a crowd assembled to praise her, but they look as if they'd gathered earlier that day as a lynch mob and only just learned the truth before Kelly came outside. They spin from outrage to adoration on a dime, and while Kelly desperately seeks their approval, she must also understand how meaningless that approval is.

It's a devastating indictment and goes some way toward explaining why the director, artistically liberated, all too soon found himself without work. After The Naked Kiss, Fuller would only make one theatrical film (Shark!, which he disowned) and spend the rest of his time in television until he rebounded with his most personal yet epic film, The Big Red One. The Naked Kiss may not be the strongest film in the director's canon, but no other movie so nakedly displays his contradictory, meaty, throat-grabbing style in such overwhelming force. No wonder the industry retreated from him after this.