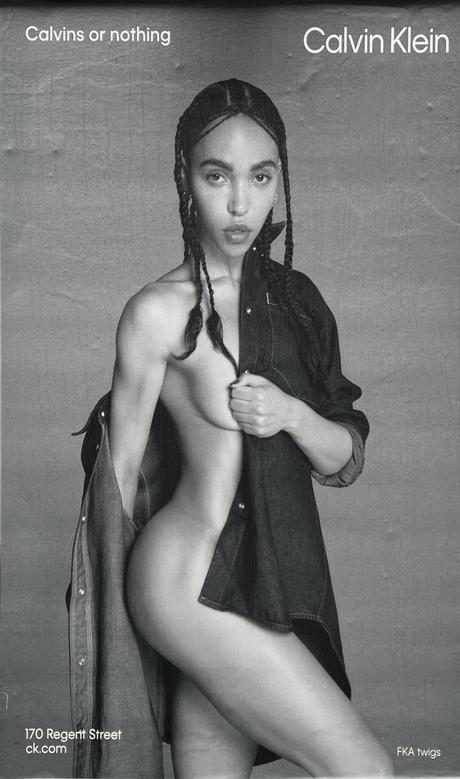

In the week that Calvin Klein went viral with its latest underwear ad, featuring The Bear's Jeremy Allen White, showing off a side of his striking abs, another campaign made news for very different reasons. The brand's 2023 image of singer FKA Twigs wearing a denim shirt with the long-standing slogan 'Calvins or Nothing' has been banned in Britain.

Twigs' ad was deemed 'likely to be offensive' by a watchdog after two complaints. The ASA said that "the composition of the image placed viewers' attention on the model's body rather than the clothing being advertised", calling it "overly sexualised". Refuting the campaign's negative labeling, Twigs has praised esteemed photographers Mert and Marcus for "I see a beautiful, strong woman of color whose incredible body has overcome more pain than you can imagine," she wrote in a statement on Instagram, which she shared alongside the banned image. She added: "I don't want to have my story changed."

There is no irony lost in the fact that Allen White's images are still the object of the Internet's affection, called "a shareable feast" by the New Yorker for fans of the on-screen chef and his Iron claw-sharpened body. The photos remind us that sex sells, as long as it's served in a way the internet finds palatable.

Double standards aside, it's no surprise that Calvin Klein's ads have gone viral or been banned for their overtly sexy compositions. Pushing buttons by making their models undo them has been the backbone of the brand since 1980, for better or for worse. Brooke Shields, then just 15, famously uttered the same refrain featured in Twigs' ad for a CK jeans commercial ("You want to know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing"), which got her banned by two networks were taken off the air in the US.

But of course, Calvin Klein and his group of photographers didn't invent the provocative ad. Innuendo, eroticism and blatant nudity have been used to sell luxury fashion and beauty products for decades. As Alice Farmiloe, a luxury brand strategist, reminds us: "PT Barnum once said, 'There is no such thing as bad publicity.' Bold advertising is intended to spark debate. It must always try to push the boundaries of what considered 'safe' and 'acceptable'." But adds that, crucially, only: " as it feels true to the brand's agenda. Brands that want to carve out a place in culture must share their POV with the world."

The story continues

Holding a mirror up to a moment in culture, often through attitudes toward nudity and sexuality, is a strategy long employed by the world's most recognized designers and photographers. Many of them have become known over the years as master provocateurs. Yves Saint Laurent started a series of remarkable nude advertisements when he himself was captured in 1971 (a decade in which the feminine Page 3 was inaugurated) by Jeanloup Sieff (a decade in which the feminine Page 3 was inaugurated) for his eponymous Pour Home fragrance. Later it was made into a jeans advertisement.

Then who could forget Wonderbra's uplifting 'Hello Boys' ads from the 1990s starring Eva Herzigova? Apparently they have led to traffic jams and, according to some, even accidents. Tom Ford has never been afraid to be subversive or downright sexual in his advertising - see his 2003 Gucci ad with Carine Roitfeld, which featured a model on their knees unbuttoning someone else's underwear to reveal pubic hair in the shape of the iconic G of the brand. was the era of the heyday of the Brazilians and Sex and the City.

Unfortunately, some provocative behind-the-scenes advertising speaks to a darker story. When pushing boundaries, there have been campaigns that have caused damage. Kate Moss starred topless opposite Mark Wahlberg in a 1992 Calvin Klein ad at the age of 17. She has since spoken on an episode of Desert Island Discs about how she has "not very fond memories" of the underwear campaign, which made her so anxious made her have to take Valium leading up to it. Moss agreed with host Lauren Laverne that she felt objectified, saying she was "vulnerable and scared."

The 2000s created a major storm with the spread of nude fashion. When Sophie Dahl posed nude for Yves Saint Laurent's Opium, it received almost 1,000 ASA complaints, with some calling it "degrading". Although it didn't stop the brand from launching another full-frontal campaign for the men's fragrance M7 two years later. In a decade when women's bodies were under fire in the media, it's no surprise that clothing in some campaigns was secondary to the highly sexualized bodies of mostly female models. Especially when disgraced men like Dov Charney headed the then hugely popular American Apparel and Terry Richardson then shot campaigns for luxury fashion giants (both of whom deny the sexual assault allegations against them). The fact that American Apparel was selling spandex leggings, stockings and basic T-shirts probably passed many people by because it was the model's akimbo poses that started the conversation.

Of course, it's not just semi- or full frontal nudity that causes fashion brands to receive criticism for their marketing. Take Sisley's "Fashion Junkie" ad, in which two models stretch out over a white dress, which was banned in the 1990s for glorifying cocaine. While political issues ranging from the death penalty to the treatment of AIDS victims in the 1990s were conveyed in advertisements by the United Colors of Benetton brand, which became known during this time for its ability to shock with billboards.

And fast forward to the 2010s, when women's bodies were the subject of furore in clothes this time, as models including Kiki Willems, then 18, were chosen for Hedi Slimane's Saint Laurent spring 2015 ads. In a clear nod to Slimane's rock 'n' roll aesthetic, Willem's petite body appeared collapsed on the ground, with her chest and ribs visible in the low-cut dress. Out of concerns about body image, the ad was banned because the ASA made it look "unhealthily thin".

In the age of social media, brands are still willing to walk the line between virality and backlash. As fashion photographer Louis Bever argues, the allure of social media fame can only fuel the desire to court controversy. "Brands like Benneton used 'controversial' images to provoke audiences and stand out from the competition. However, when the response gained attention, it resulted in increased sales. Brands still do this today for similar reasons. out, and adding a provocative image or message behind it means it will spread like wildfire in an age of 'viral' culture."

Controversy is a powerful marketing tool. People criticize FKA Twig's ad for not having a 'story', but not all ads need that.

It may seem surprising that bold ads have endured even in the age of cancel culture, though not a season goes by without the site Diet Prada-who have become the unofficial watchdogs of the fashion world-posting an ill-conceived or, frankly, tone-deaf campaign that was set up to stand out. Few have matched the scandal and disgust caused by Balenciaga's so-called 'bondage beer' campaign featuring two young girls from late 2022. The appeal of provocation remains for the same reason it always has: to make people feel something." Numerous studies have shown that creating an emotional response in an audience is the best way to build salience and be remembered," says Farmiloe. "Controversy is a powerful marketing tool. People criticize the FKA Twig ad for not having a 'story,' but I don't think all ads need that."

What content has the power to provoke people can change as quickly as the latest TikTok craze, but as long as they have the resources, brands won't stop looking for the sweet spot of shock and awe. And as Twigs has proven, even after the ads are banned, they will live on in the Internet age.