We all know and love London’s plaques – blue or otherwise. They pop up on our London Walks like cultural buttons waiting to be pressed by our London Walks guides.

We all know and love London’s plaques – blue or otherwise. They pop up on our London Walks like cultural buttons waiting to be pressed by our London Walks guides.

Regular Daily Constitutionalists will know that we have already rounded up 100 of ‘em for our Plaque of the Week series (search “Plaque of the Week” in the top left corner of this window).

London Walkers often ask about them. Why are some blue and some green? How do property owners feel about them? How can one “qualify” for a plaque?

Our mission in this, our occasional series, is to extend this conversation… by issuing our own plaques to those who have been left out. You may have a thing or two to say on such matters. As usual, get in touch via email or on Twitter @londonwalks.

David writes…

“Figuring this place out, making connections.” “Getting a read on this endlessly fascinating city, getting it into deep focus.”

Etc.

This job – being a London Walks guide – that’s what you do. You pick up a trail and follow it.

Yesterday I was moseying along through the territory – my mental landscape – moving along a fairly familiar track. A trail crossed it. Hmmm, wonder where that goes?

Broke off what I was doing – where I was going – and followed the trail I’d picked up.

Crossword puzzles. Cryptic crossword puzzles. British crossword puzzles.

Sometimes you just want to find out where the trail goes, what it’s going to lead to.

Especially if it’s going to help you figure this place out.

You get a read on some of these neighbourhoods – get a feel for them – one really strong impression you get is that just about every house in a street could have a blue plaque.

That’s why “blue plaque guiding” – and it’s not guiding by our standards – is laughable. “Blue plaque guiding” compared to what’s there – well, it’s probably the same ratio as the part of the iceberg that’s above water to the part of it that’s beneath the surface. 9/10 of it’s under water.

So, regrouping. Picked up the trail of that most English of cultural phenomena – cryptic crossword puzzles. Where’d that trail lead?

Led to 1926. To the literary critic Edward Powys Mathers landing the job of setting crossword puzzles for The Observer. He’s a literary critic, remember. Knows literature, loves language, understands its possibilities, is very skilled at wielding it.

He begins to seed his crossword puzzles with puns and anagrams and bagatelles of wit.

That’s the beginning. Mathers is the founding father of the cryptic crossword puzzle.

So, sure, wanted to know more about Edward Powys Mathers. There’s a little bit on Wiki. Born 1892. Public school and Oxford educated. Translator and poet as well as critic. Son of a newspaper proprietor. Born in Forest Hill. And that’s pretty much it for Wiki. Thin fare, even unto getting the year of his birth wrong.

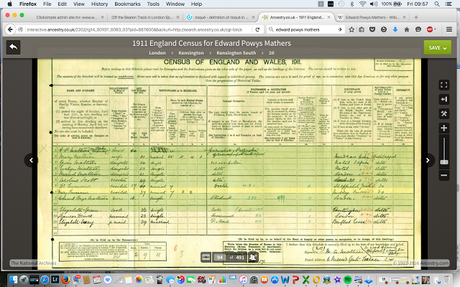

Looked elsewhere. Fetched up this. Edward Powys Mather’s appearance in the 1911 census. Grade A stuff.

In no particular order…

He was 18 at the time of the census. A student.

The family house – 6 Queensgate Terrace in Kensington – had 17 rooms.

There were 11 people – all British – in the family house the day of the census.

Nine females, two males.

Edward, his mother, his three sisters, two visitors – family friends, one assumes, a doctor and his wife – the 36-year-old cook (she was from Huntington), a 23-year-old London-born housemaid, and a 39-year-old parlour maid from [illegible].

The “Head of the House” as the census puts it, Edward’s father, was in Italy at the time.

Edward was born in London. He had three older sisters. There was also a sibling who’d died.

His mother was 51 in 1911. She’d been born in Madras, India. His two older sisters – 24 and 23 at the time of the census – were born in Natal in South Africa. His 21-year-old sister was born in London. (Aside: we know from that that the family weren’t in South Africa during the Boer War. And also that that was quite a bit of childbearing for Edward’s mother – four in five years. One wonders of course when the sibling who died was born.)

There on that one page – indeed, that one life, Edward’s mother’s life – you’ve got a thin but telling crosscut of the British Empire: she was born in Madras, India; she bore two children in Natal, South Africa; and at least one more in London.

And there’s a very strong whiff coming off that census page of how terribly circumscribed the lives of the “help” – the servants – must have been. Certainly in comparison with the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Mather and their offspring.

And let’s just widen the view for a minute. Let’s meet the neighbours.

Next door, No. 4 Queensgate Terrace, is a 12 room house. The Knights live there. Widowed, 55-year-old Francis Alice White is the Head of the Household. She had six children. They’re all alive. Two of them live with her – 31-year-old Ella and 22-year-old Elsie. A third daughter, 25-year-old Alice, is married to 41-year-old Charles Mortimer. They’re on a visit to 4 Queensgate Terrace. The son-in-law, Charles Mortimer, catches the eye. He was a barrister; he’s now an artist, a painter. The parlour maid is 26-year-old Maria Meadows from Lynn in Norfolk. The housemaid, 27-year-old Annie Chesfield was born in Brixton. The cook, 25-year-old Maude Hardy, is from Lambeth. The “between maid” – she assisted both the cook and the housemaid –16-year-old Dorothy Jones, was from Shepherd’s Bush. Finally, there’s 29-year-old Henry Knight. Born in Putney. In the relation or household position box an entry’s been crossed out and something else scribbled in. Ancestry’s gloss is that he was a servant. But with the same surname as the Widow and her daughters? Surely he’s a son and brother. If not, if he is a servant, there’s no question but he’s the wild card under that roof. A 29-year-old male servant in an otherwise entirely female household made up of five young women (not counting the widow) ranging in age from 16 to 31.

Phew! What’d the neighbours make of that if the Ancestry gloss is in fact correct?

And next door in the other direction? At 8 Queensgate Terrace we’ve got 53-year-old Dr. Brinton and his family and servants in an 18 room house. Dr. Brinton and his wife Helen Constance – she’s 47 – have been married 20 years. They’ve got three children, only the youngest of whom, 19-year-old Mary is living at home. Mary’s a student at London University. Dr. Brinton’s sister, 51-year-old Marion lives with them. She works – she’s a “sick nurse.” There are three servants. The parlour maid is 28-year-old Annie Garrett from Windsor. The house maid is 25-year-old Maria Leeder from Norfolk. The cook is 30-year-old Ada Parker from Suffolk.

Further along the street a Retired Admiral, a stockbroker, the Private Secretary to the Lord President of the Council, a chartered accountant, several Colonels (including Colonel Campbell, a Canadian), the Persian Minister in London, an MP (just round the corner) and any number of Household Heads whose occupation was looking after their “Private Means.”

And the size of those houses – 18 – 20 rooms every single one of them. In stark contrast to the 3-room houses the same census taker put in at round behind Queensgate Terrace.

These are the merest snapshots, these census returns. But they’re telling snapshots. They give us a feel for that part of Kensington a century ago. The sort of people who lived there, the circumstances of their domestic arrangements, where they’d come from, where they’d been, the straw in the Lottery of Life that everybody under any one of those given roofs had drawn, etc.

And finally, it’s pure pleasure to be able to point out No. 6 and say, “you know British crossword puzzles – cryptic crossword puzzles – uniquely British and a very different cup of tea from American definitional crossword puzzles? In 1911 an 18-year-old was living here with his parents. His name was Edward Powys Mather. Fifteen years later he took charge of The Observer’s crossword puzzle and changed it out of all recognition. Changed it from definitional to cryptic. You’re standing in front of, you’re looking at, the boyhood home of the father of the British Cryptic Crossword Puzzle, ladies and gentlemen. It’s a 17-room house – at one letter per room that’s enough rooms for two or three words in a crossword puzzle.”

Or words to that effect.

Pretty satisfying to know that. To know some things that other people don’t know.

A London Walk costs £10 – £8 concession. To join a London Walk, simply meet your guide at the designated tube station at the appointed time. Details of all London Walks can be found at www.walks.com.