When Borges wrote his Book of Imaginary Beings he forgot to include a chapter dedicated to soccer goalkeepers. A simple and consistent taxonomy classified them within fixed animal categories: jaguars, lions, tigers, cats, and spiders as well. The greatest of all, Yashin, whose real name was Leo, was known as the Black Spider. He reached the national team by dethroning a goalkeeper, Alexei Khomič, who was in turn nicknamed the Tiger. And a black giant Yashin seemed to Sandro Mazzola, on November 10th, 1963; subjugated by the unusual spider nestling in his net, wrapped in the silky cocoon of his will of ice, Mazzola threw his penalty right where Yashin was diving, annihilated by what he himself called ‘a monster’.

Usually, goalies have something of the street charlatan: they are colorful, flashy, with vulgar and often eccentric movements. Equipped with a kind of mesmerism, they charm the strikers as a flute player the cobra in a basket. Illusionists, they stretch their bodies out of proportion. Thus, the goalkeepers carry with them a gypsy imagery, of wild animals and magics—they are the world’s tallest man, the snake charmer, the tightrope walker, the most circus-like of all players. Yashin, of all this, retained only the hypnotic skill and the ability to magically change his arts.

Despite his name, Lev Yashin had also little to do with the leonine type outlined in the treaties of physiognomy. The fate had assigned him a life that seems the script of a bad B-movie about the Cold War. He was born in Moscow from a working-class family, and was himself a factory worker, when he was not a hockey goalkeeper. He was later awarded the Order of Lenin. His life knew popular tenements, factory bolts (which his colleagues pulled to him to test his sensational reflexes) and lots of vodka—the same vodka that he himself, perhaps teasingly, said he was drinking before the match, and that would bring him the awful retribution of a leg amputation and a death from cancer. A Soviet existence, epitomized by the ugly monument built for him: two steel poles arranged in a pyramid, with him glued at the top leaning toward a ball—a botched cross between the cabin of a poor Nativity, where the angels, their wings chipped, are attacked with a thumbtack, and the funerary monument to Antonio Canova.

And yet, if we use the category of a fellow of citizen of Yashin, Mikhail Bakhtin, who lived and died in Moscow, and we try to understand the true chronotope of Yashin, we realize that it is not the Stalinist Russia of the Fifties and Sixties, but Germany’s early nineteenth century. Yes, Yashin should be in a short story written by Hoffman and Chamisso. Imagine a mysterious Russian arriving in a velvety German spa town: tall, mighty, broad nose and full lips, hair impeccably combed on the right, dressed in black, eyes of ice, the iron grip of the hands, movements both darting and harmonious. (And the stare that subjugates, with a portentous mesmerism.) This was Lev Yashin: a man who would have unleashed the morbid curiosity of young middle-class girls playing whist. From that black monster had to emanate a slightly sulphuric aura. Yashin knew, according to the comrades, how to sense the game before its development; he knew what would happen and, as an enchanter, he could direct the ball where he wanted.

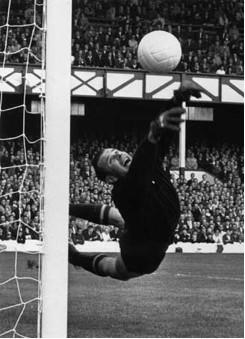

There is an image of a player who, his socks down, starts a counterattack, alone, from his own half. Yashin looks at him, waits for him, still on the line of the small box and does not advance. He challenges him. And at the time of the shooting, he spreads prodigiously, removing the ball from a post shrunk like after a charm from Alice in Wonderland. This makes the difference between a great goalkeeper and a circus acrobat, these two twins. The goalkeeper is a surveyor, a cartographer; he calculates trajectories, curves, wind effects. Everything is both reason and muscular (re)action. The keeper acts prompted by a mysterious sense of time and space, he realized with the whole body where the ball is, without seeing it, as we see in the still image of Yashin’s famous save against Czech Republic. It just so happens, as it did to Gordon Banks, that you make the most beautiful catch in history and then you notice it only because your teammate runs up, and Pelé is looking fiercely at you.

The images of an aged Yashin are often merciless. They sometimes portray him adorned of honors and medals, a saint readied for procession, a bad lay, sometimes is swollen, possibly alongside a Pelé of resin and wax, a conceited saint of himself. Or else he is portrayed engrossed in a conversation with a young goalkeeper who wears a blue jumpsuit, with patches of white in his knees like a child. That goalkeeper is Rinat Dasaev and shares many things with Yashin: the feline nickname of the Cat, the captain’s national armband, the essential movements, the sober and perfect style, and alcohol. Which puts him in a car crash: an accident that injures his hand. For a goalie, maybe only an injury in the eyes would be worse, like what happened to Gordon Banks, who was deprived of sight in one eye, even in this case as a result of an automobile accident. (These are tragic stories, certainly not grotesque as Peter Shilton’s incident, which destroyed the car because, an awkward seducer, he was trying to escape a husband who had surprised him flirting with his wife in the vehicle).

Instead, in the 1982 World Cup, women judged Rinat both as a dark seducer and the perfect family man; when he returned to Russia after the incident, in 1991, the wife and daughter of this perfect father were gone. Carlo Goldoni, after the presentation of his play One of the Last Nights of Carnival, stepped outside the lurid scene of St. Luke, and about to leave for Paris, he spoke to the audience in tears, crying: “It’s not the first time, this, that I leave; and everywhere I have been, I took the name of Venice engraved in my heart… “. Goldoni did not know that, in a few years, there would be no return to Venice, or that Napoleon was to take it away from him. So for Rinat. Off to Seville in 1988, with the consent of the Party and a contract of 180 million pesetas per month (150,000 of which for himself), did not know that he would never again found his Russia, swept away first by Gorbachev and then the Coup. No more CCCP on the jersey worn 91 times.

This was dramatic, even for a Nicodemite Muslim who had to come to terms with his identity on a daily basis; it was difficult even for somebody born in Astrakhan, the city destroyed by Tamerlane, besieged by Ivan the Terrible, fought over by Cossacks, Turks and Persians alike. It could not be a coincidence that the city had also seen the birth of Joseph Deniker, a naturalist and anthropologist who studied a map of the European races divided into ten categories. In this city of Persian and Armenian merchants, a crossroads for the East, a mixture of races from an imaginary caravan had to be palpable.

Dasaev, however, was never a circus-man, like Yashin before him. His amazing sense of position made him arrive with seemingly ridiculous ease everywhere. When needed, his thin legs made him fly to remove impossible balls. Rinat was always trying to pin the ball down the line. He was different from the many great goalkeepers of his generation—Zenga, Preud’homme, Pfaff—because of his Soviet efficiency. Perfect mechanisms allowed him to limit the gestures, and to combine effectiveness with only a minimal indulgence for the show.

Dasaev turned fifty in 2007 and was celebrated in a half-empty stadium where the speaker commenting on the match had a horrible echo effect taken from a military parade. The Cat was no longer himself. With the atmosphere of Goodbye Lenin, one could see him moving slowly and clumsily, although the figure, wrapped in the proverbial gray shirt, which he alternated with the yellow one, had still his elegant style of walking, as on the springs of a mattress. There is a real Götterdämmerung captured on camera, in which an overweight Maradona passes a surprised Dasaev with a free kick low to the ground. The real Maradona would have lifted the angle to the intersection; the real Dasaev, whom they called Iron Curtain, would fly to remove it from there. No God or Cortina, no mysterious power has saved Yashin, Dasaev, Maradona from their hells. Yashin lost a leg as Rimbaud, Maradona is still alive, but dull as Anthony Patch in The Beautiful and Damned. Dasaev, the Cat, after having lost everything, lives one of his lives in the organizing committee for the 2018 World Cup, to be held in Russia. And, perhaps, he’d sing as Bruce Springsteen sings in “Darkness on the Edge of Town”:

I lost my money and I lost my wife / Them things don’t seem to matter much to me now / Tonight I’ll be on that hill ’cause I can’t stop. / I’ll be on that hill with everything I got / Lives on the line where dreams are found and lost / I’ll be there on time and I’ll pay the cost / For wanting things that can only be found / In the darkness on the edge of town. ♦

The original Italian version of this essay is available here.