It’s war. It’s something in a uniform. It’s a different shade from mine.

War movies fall into two broad categories: those which could be described as the “Boys’ Own” variety, where heroics are celebrated and high adventure is the order of the day; and then there’s the anti-war type, films which use the horrific aspects of war as a kind of backdrop to raise questions about our sense of humanity. I think both have their place and are worthy of consideration. The latter category is frequently more interesting though, in cinematic and artistic terms, as the character of war (and I do think it’s reasonable to refer to it as such since the conflict portrayed can be legitimately viewed as a character itself in the drama) necessarily hones in on the very essence of humanity. It’s sometimes claimed that crisis and adversity bring out both the best and worst in people, and surely warfare can be viewed as the ultimate example of this. The tragedy inherent in this rawest expression of human conflict is that it divides and unites in equal measure; there’s that sense of national and international solidarity, perhaps even nobility, in the defense of an ideal, while there’s the simultaneous schism created by different interpretations of said ideal. And on an even more fundamental level, we are drawn together by common feelings regarding what is right and torn apart at the same time by the way we define it. The Long and the Short and the Tall (1961) does exactly this – it looks into the hearts of a handful of men who are bound together and also separated by their views on right and wrong.

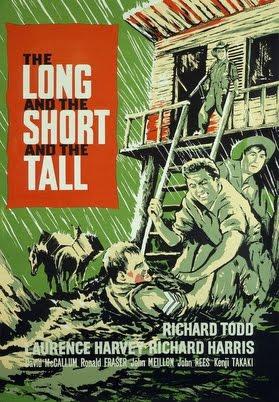

As the opening credits roll, accompanied by the First World War song Bless ‘Em All (although I certainly remember hearing an old drunk offering up a lusty rendition of this with the word bless replaced by a more colorful four letter variant when I was a youngster) and images of plants and animals locked in mortal combat, the message seems clear: the struggle for survival is truly universal and not just an affectation adopted by our own species. The setting is the jungles of Burma in WWII, and a British patrol are taking part in an exercise, one which seems almost juvenile under the circumstances. The half-dozen men under the command of Sergeant Mitchem (Richard Todd) are experimenting with “sonic warfare” – using recordings as a kind of decoy to wrong foot the enemy. Nobody likes the detail, Corporal Johnstone (Richard Harris) wants to get back to base camp and Private Bamforth (Laurence Harvey), a Londoner with nothing but contempt for the army, wants anything but his current circumstances and companions. Even in the early stages there’s friction between the members of the patrol, Johnstone needling Mitchem over his loss of a previous patrol and subsequent demotion, and Bamforth taking a pop at everyone, even the mules, mainly because they don’t hail from London. Still, this is all of little consequence, no more than the natural ribbing that arises when a disparate group of individuals have spent longer than is desirable in close proximity. The first sign of genuine danger comes when the nervy radio operator (David McCallum) tunes into a Japanese transmission which suggests the patrol might be more isolated than expected. And then an enemy soldier strays into their temporary camp. These are the two key elements influencing all that follows; Mitchem has the responsibility for seeing his patrol safely back to base but there’s also the matter of their newly acquired POW and how to treat him. If there was a touch of antagonism before, the moral dilemma now presented – survival vs humane and ethical conduct – threatens to tear the fragile unity of this group apart.

The Long and the Short and the Tall was adapted from a stage play by Willis Hall (screenplay by Wolf Mankowitz) and the theatrical origins do show in the film. Some of the early scenes do have a very stagey quality to them, accentuated by some of the acting and dialogue, but that aspect becomes less pronounced, or at least less important, as the story progresses. The whole thing, with the exception of a bit of stock footage, is shot on studio sets, which I feel actually adds to the claustrophobic feel of the piece. Erwin Hillier’s photography is sweatily atmospheric and director Leslie Norman ensures the focus remains on the men and not on the jungle set. For me, the main thrust of the film is the way pressure and extreme circumstances can change men, how their true characters are revealed by unexpected developments. The early scenes invite us to form an opinion about the patrol and even to pigeonhole the members. However, as the situation changes, as their survival is threatened, those perceptions are altered. The characteristics we might initially have thought of as strengths are shown to be flaws and weaknesses, hypocrisy and prejudice rear their ugly twin heads, and decency and honor manifest themselves from the least likely source.

Richard Todd has the leading role as the veteran sergeant, a man whose capability is never really in doubt, despite the insinuations of his subordinate. One of the more notable features of the film is the shift in character, and therefore in audience sympathy, which takes place over the course of the story. Perhaps it’s not quite as radical in the case of Todd, a hardening of attitude is seen for the most part. On the other hand, both Richard Harris and Laurence Harvey depart significantly from the expectations the audience are initially encouraged to foster. If I wanted to be critical, I could say both men lay the performances on a little thick at times, especially Harvey at the beginning. With the latter there’s a definite theatricality to his playing at first, although that’s at least partially down to the writing, but this improves as the plot develops. By the time the final act comes around the roles have been reversed, and both Harris and Harvey deserve credit for achieving this effect credibly. When a cast is small then the contributions of all the members become more important, and I was favorably impressed by the work of David McCallum, Ronald Fraser, John Meillon, John Rees and Kenji Takaki.

To my knowledge, The Long and the Short and the Tall has only been released on DVD in the UK so far. That disc presents the film full frame, which is clearly not how a movie coming out in 1961 would have been shot. IMDb suggest 1.85:1 as the correct ratio and that sounds correct to me. Aside from that, the film looks pretty good with nice contrast and little or no distracting damage visible. Sadly, there are no extra features whatsoever offered. I suppose some might complain about the studio-bound setting but I can’t say I found it problematic, the story is of the intimate, powder-keg variety so it works well enough. Personally, I find war films a fine vehicle for raising ethical conundrums and a means of focusing attention on our view of fellow men. In terms of setting and moral complexity The Long and the Short and the Tall shares some features with Hammer’s Yesterday’s Enemy, and both movies would make for an interesting double feature.