He rose before six that morning, same as usual, and donned his sweatshirt and went for a jog — three miles now, in a slight concession to age, rather than four.

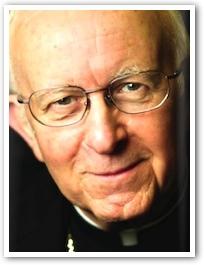

The Most Reverend John George Vlasny

Then a shower and coffee and an hour of private prayer in his home chapel. It was Ash Wednesday. A light day for appointments he says — everyone assumes you’re in church all day, which you are not, although I was celebrating a lunchtime Mass at the chancery, and the evening Mass in the cathedral. It was also his seventy-fifth birthday. An Archbishop of the Holy Roman Catholic Church, by canon law, must tender his resignation, by letter, to His Holiness the Pope by the close of business on his seventy-fifth birthday. The mail is picked up at four in the afternoon at the chancery on Burnside Street. So His Excellency John George Vlazny, Tenth Archbishop of Portland in Oregon, the second-oldest archdiocese in America (behind only Baltimore), had some seven hours, after his arrival in his office on Burnside Street at nine in the morning on Ash Wednesday of this year, to write the letter that would close his career as not only Oregon’s pastor, but first among the Catholic bishops of Oregon, Idaho, and Montana.

I figured I would tackle it as soon as I got settled in the office, he says. No sense putting it off. No, I didn’t worry about what to say. I knew what I was supposed to say but I also know what I wanted to say. I dictated the letter, as I usually do. I told the Holy Father that I was filled with the deepest appreciation for having received the call to be a bishop three times from His Holiness John Paul the Second, and that I was offering my resignation, and that I would await further information. The letter goes to the papal nuncio in Washington, and then he reports my resignation to the Congregatio pro Episcopis, the Congregation for Bishops, in the Vatican. In turn they report my news to His Holiness, and then the process starts. I am eventually asked to recommend a terna, three men I think would be excellent candidates to succeed me. The three names can be anyone in the world — I could even suggest you, which he can, we would have to see about your ordination.

I wasn’t sad or regretful, no. To be honest there was almost a little glee, after 29 years as a bishop. When I was finished dictating the letter, I left the tape in a box by the door. My assistant Rozeanne retrieved it. Our habit is that she types up letters and gives them to me to look over and sign. In this case she waited until the afternoon to get to it.

I stared at the tape all morning but I just couldn’t do it, she says. I just couldn’t bring myself to do it. I knew that I should but I just couldn’t. Finally after lunch the Archbishop said I think you better get that letter done, Rozeanne, so I did. I gave it to him at about two o’clock. He made some tinkers and I made him a clean copy and he signed that and gave it back to me. We didn’t say anything. I put it in the envelope and stamped it. I remember that the stamp had a ship on it. I walked it down to the mailroom. Outgoing mail goes in a large white bin. A postman comes for the bin. Our mail goes to the main city post office on Hoyt Street. The letter goes to Washington, and then I think it goes into the papal nuncio’s diplomatic pouch for transmission to Rome.

You know what I would like to do when I am retired? says the Archbishop. I’d like to sit by the Sea of Galilee for a couple of months. Or maybe in the hills of Assisi. Just sit quietly and think and pray. It’s been a long road from being Johnny Vlazny in the streets of Chicago to that letter. Fifty years as a priest, thirty as a bishop. Then I’d like to come home to Portland and just be on call. Visit schools, retreats, maybe teach a little. The archdiocese is in good health now. We’re out of bankruptcy, no parishes closed, the schools are all protected. The parishes are independent. I am the member of 124 parish corporations, you know. Vocations are up, Hispanics are better served, our children are protected against heinous crimes. We’re in good shape. I know that my time will always be remembered for the bankruptcy. I don’t like that, but I know how history will read.

Archbishop, I say, there are an awful lot of people who think your honesty and humility and integrity dealing with crimes not committed on your watch is what will be remembered. You said you would protect our children, and be responsible to victims, and never lie, and you kept your promises, when many other men did not.

There was a moment, says the archbishop suddenly, when I was about to sign off on the bankruptcy, which would be the first ever in the American church, but which I felt we must do, to be fair to all victims and to protect parishes and schools from closure, and I hesitated for a moment, thinking that this might well cause me to lose my job; but then I realized that if you are not willing to let go, you are not doing your job. I suppose I would like to be remembered as a man who did his job with all his heart. I never wanted to be an authority. I only wanted to be a good priest and a good man, and a teacher of the greatest lesson I know.

Right about then the Archbishop’s next appointment is announced and the Archbishop and I shake hands and I look around his office, the last time I will ever see him here, and I note three things in particular: a shepherd’s crook, carved for him by a parishioner; a walking-stick owned by his predecessor Archbishop Alexander Christie, who founded the University of Portland in 1901; and a drawing by a child. This last is positioned so that he could see it all day, every day. Every day, he saw a lovely drawing by a miracle. Every single day.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Brian Doyle. “the Letter.” Portland Magazine (Autumn, 2012).

Reprinted with permission from the author and Portland Magazine.

Portland Magazine cannot offer subscriptions; but the magazine is mailed to all donors to the University, so your gift to the University of Portland earns you the magazine twice named best in America. To make a Rise Campaign gift of any size to help the University’s hundred efforts to help and heal kids, see rise.up.edu.

THE AUTHOR

Brian Doyle is the editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland, in Oregon — the best university magazine in America, according to Newsweek and the author most recently of The Wet Engine, about “the muddle & mangle & miracle & music & miracle of hearts”. Doyle is the author of thirteen books in all: six collections of essays, two nonfiction books (The Grail, about a year in an Oregon vineyard, and The Wet Engine), two collections of “proems,” most recently Thirsty for the Joy: Australian & American Voices, the short story collection Bin Laden’s Bald Spot, the novella Cat’s Foot, and the sprawling novel Mink River. He is also the editor of several anthologies.

Copyright © 2012 Portland Magazine