Nature writing is such an intriguing genre. It’s so quiet and unassuming in its PR that you might not expect it to have such an honorable and long-standing history (Thoreau, Peter Matthiesson, Nan Shephard, Barry Lopez, J. A. Baker) or the capacity to produce extraordinary narratives like Pilgrim at Tinkers Creek by Annie Dillard and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. To this day, it’s a powerful form of storytelling still, with contemporary superstars like Robert Macfarlane and Roger Deakin. And yet unlike just about every other storytelling medium – film, television, news media and books – it eschews sensationalism and melodrama. Given that our environment is in the midst of one of the toughest of wars with mankind ever, it could be forgiven for ramping up the drama content, but no, the books I read continue to speak in the most serene of voices. Perhaps that’s precisely the charm.

Nature writing is such an intriguing genre. It’s so quiet and unassuming in its PR that you might not expect it to have such an honorable and long-standing history (Thoreau, Peter Matthiesson, Nan Shephard, Barry Lopez, J. A. Baker) or the capacity to produce extraordinary narratives like Pilgrim at Tinkers Creek by Annie Dillard and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. To this day, it’s a powerful form of storytelling still, with contemporary superstars like Robert Macfarlane and Roger Deakin. And yet unlike just about every other storytelling medium – film, television, news media and books – it eschews sensationalism and melodrama. Given that our environment is in the midst of one of the toughest of wars with mankind ever, it could be forgiven for ramping up the drama content, but no, the books I read continue to speak in the most serene of voices. Perhaps that’s precisely the charm.

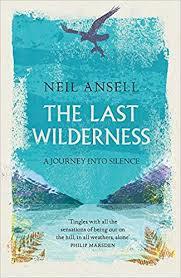

Neil Ansell is the author who got me into nature writing, and so a new book of his is always an event. I know absolutely nothing about nature. I can identify a horse chestnut tree, a willow, a silver birch and probably an oak. I can point out a blackbird and a robin and a pigeon. I have a back garden with some plants in it. That’s it for me. So I never thought I would fall head over heels for the nature genre; but then I read Neil Ansell’s account of living alone in the Welsh countryside for five years, Deep Country, and was bowled over. This is what reading is all about: the invitation into an unknown world made real and vivid and inhabitable by the skill of the writing. When his second book came out, Deer Island, I made sure to secure a review copy and absorbed it in the same kind of trance as before. And now with his third, The Last Wilderness, I tried to hold back a little and understand what it is about his writing that is unique to him, and why I find it so affecting. It’s really hard to put my finger on, but over the course of this review, I’ll try.

The Last Wilderness concerns five visits taken over the course of a single year to the Rough Bounds in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland, one of the few places in the British Isles to contain truly ancient wild land, almost untouched by human society. Ansell traveled there first as a young man, just embarking on many years of rootless wandering, and he decided to revisit it now that those years may be coming to an end due to failing health. With each trip he explores a different part of the region, endures the changing seasons, battles his own body and allows the present moment to trigger a rich web of memories drawn from other travels in other times and places. What matters to him throughout his wanderings is the quality of experience.

I can see an animal in a zoo, up close and personal, and yet it feels as if it barely even counts, I can watch a television documentary, and gain an intimate insight into the private life of an animal, and yet it is no substitute for the real thing. Nothing can compare to the joy inspired by even a brief encounter with a scarce and beautiful wild animal in its natural element. It is not about what I have seen, it is about forging a momentary connection with the wild and finding a place in the world for my own wild heart.’

And forging a connection is something he continually does, often with unexpected results:

As I walked the path one scorching hot day, the air flexing in the rising heat, I saw a crow walking the path ahead of me. I kept expecting it to flush as I approached, but it never did; instead it hopped up and perched on top of my head. I felt strangely proud as I continued my way towards the harbor with my animated headdress. And then it drove its beak into the very top of my skull as if it was trying to crack a nut.’

There’s an exquisite attentiveness throughout the narrative , not just to animals but to landscape too:

An individual wood can have some intangible quality that makes it stand apart from all the other woods. This one somehow felt different from the other birch woods I had traveled through. The birch is part of a natural succession. It is quick to take hold, and it will usually be the first tree to grow on neglected land, before finally giving way to oak or whatever other tree forms the climax vegetation of the locality. Here, it was a permanent fixture. Nothing else would ever take its place; it was as though it had finally been able to step out of the shadows, out of its role as supporting act, and fulfill its true potential.’

And I also appreciated the attentiveness Ansell pays to his own authentic nature as it is shaped by his environment; the nomadic times in which ‘the shock of the new gives me an intensity of experience, a sudden depth of focus that will perhaps never be replicated’, and the settled times in which extended periods in one place allow him to ‘become gradually aware of how things are more subtle and complex than they first appeared, of how malleable and mutable is the world’. And as a person who can be entirely self-sufficient, there’s an insightful meditation on what it is to be solitary: ‘Empathy is not a zero sum game; caring about nature does not mean you care less about other people.’ The benefits of solitude are to be found in a kind of emptying out of the social ego, leading to a heightened state of sensory arousal, in which the relationship to the external world can strengthen and deepen.

If I quote extensively here, it’s because the voice feels so unusual to me in a clamouring, chattering world of rapid and mostly superficial thought. The Last Wilderness charts all manner of loss – loss of the virgin earth, untrodden and unspoiled by mankind, loss of so many species of animals, loss of Ansell’s hearing and loss of his confidence in his personal strength as he begins to suffer from an undiagnosed heart condition. But to my mind, the loss that is most striking, but which is noticeable in this book precisely because it contains so much of it, is loss of a certain state of mind. Ansell is an unusual man. He is solitary and contemplative, accepting and philosophical, non-competitive and non-materialistic, keen on simplicity but not on what is simplistic, and deeply respectful of the land and all it contains. He conjures up so much time in this book, slows down the reader’s mind, and shows us what can be accomplished with a mind that is wide open to everything in the vicinity. That state of mind is as much an endangered species as the mountain gorilla and the Siberian Tiger. Perhaps that’s why inhabiting it in a book feels very precious.

Advertisements &b; &b;