Once, off the hump of Brazil I saw the ocean so darkened with blood it was black and the sun fainting away over the lip of the sky. We'd put in at Fortaleza, and a few of us had lines out for a bit of idle fishing. It was me had the first strike. A shark it was. Then there was another, and another shark again, 'till all about, the sea was made of sharks and more sharks still, and no water at all. My shark had torn himself from the hook, and the scent, or maybe the stain it was, and him bleeding his life away drove the rest of them mad. Then the beasts took to eating each other. In their frenzy, they ate at themselves. You could feel the lust of murder like a wind stinging your eyes, and you could smell the death, reeking up out of the sea. I never saw anything worse... until this little picnic tonight. And you know, there wasn't one of them sharks in the whole crazy pack that survived.

That little speech that Orson Welles' character just casually produces on a nighttime beach in Acapulco in The Lady from Shanghai (1947) neatly encapsulates the frantic greed and self-destructive instincts at the heart of the story. In a way, I suppose you could say it catches the flavor of film noir itself, that bleak and dark form of cinema which emerged in the years when the world was clawing its way out of the financial abyss it had slid into and was poised to dive into another even more nightmarish period. It must have seemed that a humanity drunk on blood lust was bent on tearing itself to pieces. Yet for all its nihilism, film noir was also an ideal vehicle for experimentation, and there were few better qualified than Welles, that natural-born envelope pusher, to try to extend the boundaries a bit further.

The tale told begins in a deceptively simple manner with Michael O'Hara (Orson Welles) chancing upon the titular lady from Shanghai, Elsa (Rita Hayworth), as he saunters through Central Park of an evening. There's a foreshadowing of sorts of the Grand Guignol drama and chicanery to come when Elsa speaks of her White Russian background and spells as a professional gambler in Shanghai and Macao, while O'Hara spins equally beguiling yarns about his opinion of jails around the globe and his having killed a man in Spain. A bit of convenient chivalry and heroics grabs Elsa's attention and leads to her lawyer husband, Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane), offering O'Hara a job. That job is sailing their yacht around the coast, via the Panama Canal, to the west and San Francisco. It's as this odd party makes its way south, towards the tropics, that the emotional temperature rises correspondingly and approaches feverish proportions off Mexico. As the atmosphere grows increasingly rarefied and O'Hara finds himself falling under the spell of the enigmatic Elsa, he is approached by Bannister's partner Grisby (Glenn Anders) with an unusual proposition - he wants O'Hara to kill him. A scenario that has been strange and off-center up to this point now spirals down into a positively surreal vortex of cross and double-cross, where motives and desires become hopelessly entangled.

Welles took a twisty, convoluted but not especially remarkable noir story, If I Die Before I Wake by Sherwood King, and ran with its outrageous central premise, that of a man seeking out another who will be willing to take responsibility for killing him. While the essence of the plot is retained by Welles, he opens it out and brings his own characteristic style to bear. Although the scope and geography of the source novel is expanded the vicious intimacy of the amoral group at the heart of it all remains. The shooting style favored by the director and his casting choices mean that the distinctly odd characters of the book are transformed into a veritable gallery of camp grotesques, His real masterstroke was the climax, fitting in a dramatic escape from custody, a chase through Chinatown and that famous final confrontation in the abandoned amusement park, culminating in the hall of mirrors shootout. None of that appeared in King's novel, which is effectively suspenseful but not really cinematic in any way. Even if what we have today is only an approximation of Welles' vision, due to studio imposed cuts, it still provides a lesson in how to successfully adapt a piece of literature for the screen - keep important details of the plot intact, and the attendant tension, but have the courage and self belief to add the kind of visually audacious touches needed to create a cinema experience.

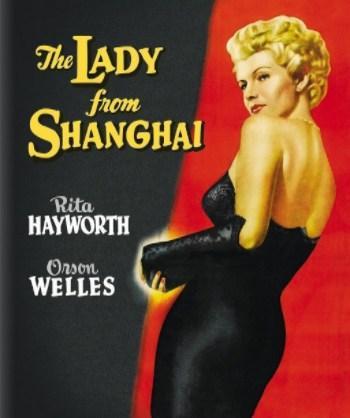

I started this post by mulling over some characteristics of film noir, and I'd like to run with that a little further here. As a style of moviemaking or storytelling it can be viewed as a collision of opposite sensibilities: the soft-hearted vs the hard-headed, romanticism vs pragmatism, the idealistic vs the materialistic. And The Lady from Shanghai carries that through in its casting. On the one hand, we have Welles himself, all affected blarney and bemused infatuation. While on the other hand, there's the venal self-absorption of everyone else. A bleached blonde Rita Hayworth is at the center of it all in a role which sees her beauty exploited to the full as she seeks to beguile Welles on screen and, by all accounts, off it too. Everett Sloane moves jerkily through the tale, his twisted leg defining his physical and psychological weaknesses but, curiously, losing some of the bitterness and regret his character in the book suffered from. Instead we see a more sardonic side to him, and his playing off Glenn Anders' comically creepy law partner is among the highlights of the picture. Add in a rat-like and oily Ted de Corsia and we have a full house of larger than life performances to enjoy.

The new dual format Blu-ray/DVD from Indicator in the UK is another of their typically stellar presentations. While I don't have any of the previous US Hi-Def releases of the movie to compare, I'd be surprised if this version has been bettered. The transfer of the film is based on the 2012 Sony 4K restoration and looks terrific. This is a dark film and the deep blacks draw you into the depths of its shadows. It's been said that high-definition offers a more immersive experience and that's a term I feel is particularly appropriate in this case. As usual, the supplements are both extensive and attractive. There's a commentary track by Peter Bogdanovich as well as a twenty-minute video "discussion" - carried over from the old DVD - by him. There's another 20+ minute filmed feature with Simon Callow along with a short extract of a 1970 interview Rita Hayworth did for French TV. Additionally, we get a brief trailer commentary from Joe Dante and an image gallery. The booklet is up to the label's usual high standards - 40 informative pages with an essay by Samm Deighan, and extract from associate producer William Castle's memoirs, detailing his experiences in the making of the film, a reproduction of the 9 page memo Welles sent to Harry Cohn regarding the changes made to his work. And all of that is rounded out by some comments by the restoration team on the challenges they faced.

The Lady from Shanghai is a movie whose reputation has grown over the years after its initial poor box-office performance. What we have today isn't quite what Welles wanted but it's by no means a poor film - there are flaws to be sure but the flair, inventiveness and sheer passion for filmmaking of its director is apparent in every frame. If you like film noir or Welles, or just absorbing cinema, then it's a must see. And the new package, transfer and extras, put together for this release is as good as anyone could wish for.