© Manu Cornet www.bonkersworld.net

I’ve just spent nearly an entire week trying to get my head around ecosystem services (ES).

You’d think that would have been a given based on my experience, my research, my writings and the fact that I’ve just spent the last week with 400 ES specialists from around the world at the 5th international Ecosystem Services Partnership (ESP) Conference in Portland, Oregon, USA.

Well, prior to this week I thought I knew what ES were, but now I think I’m just a little more confused.

Of course, I’m not talking about the concept of ES or what they are (hell, I’ve written enough about them on this blog and in my papers); my problem is understanding how we as society end up valuing them in a practical, sensible and feasible way.

So I’m going to describe the ESP Conference as I saw it, and not necessarily in chronological order.

First up is the term ‘ecosystem services’ itself – horrible name, and something rammed home again after attending the conference. Most people on the planet that are not scientists (that would be nearly everyone) just might have the most tenuous and ethereal of grasps of ‘ecosystem’ in the first place, and I’d bet that 99 % of most undergraduate students couldn’t provide a comprehensive description. This is because ecosystems are mind-bogglingly, chaotically and awesomely complex. Just ask any ecosystem ecologist.

The second part of the term – services – is particularly offensive in its presumption and arrogance. It’s not like you ring up an ecosystem and get it to clean your carpets, or fill your water tank or gas cylinder. No, the natural world did not evolve to pamper humanity; we are merely part of it (and bloody efficient at modifying it, I might add).

So try to sell this ‘incredibly complex thingy’ that is ‘there to do some (intangible) shit for us’ to the public, policy makers and politicians, and you mostly get a dog’s regurgitated breakfast and some blank, slack-jawed stares.

No bloody wonder the ES mob has had such a difficult time. We can barely make carbon trading work, and that’s one of the easiest ones to sell! Bob Costanza (ESP 2012 organiser and ‘value of nature‘ celebrity) stated in his opening talk that at Rio+20 everyone agreed with vigorous nods of the head that ES and ‘natural capital’ are very, very important indeed – unfortunately, no one did a bloody thing about it (i.e., no commitments made).

So we need a new name for starters. I’ve previously introduced ‘biowealth‘ as an alternative to ‘biodiversity’, but that hasn’t yet taken off. However, I think it encapsulates the ‘value’ part of things well for ES. Maybe something like ‘biowealth advantage’ (sounds like a health care insurance policy), ‘biowealth resource’, or some such term. Maybe you can suggest some others.

Bob also said something that rang true with me – monetising ES doesn’t mean privatisation. We should be able to trade public goods without greedy corporations monopolising things like air, water and pollination. Imagine that hell on Earth.

A keynote speaker, Pushpam Kumar of the UN Environment Programme, also said something rather simple, but profound. It’s really only when we don’t have something that we value it (value of rarity), which means in the case of ES that we don’t tend to have the political will to value them until our ecosystems are so degraded that we risk losing them. Not a good starting point. He also stated something about how we shouldn’t think of most ES in terms of their equivalent ‘replacement’ costs (i.e., what it would cost us to replace if we had to do it manually – think millions of farm workers pollinating flowers with a paintbrush). The fact is that most ES cannot be replaced (we won’t be inventing billions of tiny robotic bees to pollinate our crops any time soon), so the concept is rather unhelpful. Kumar’s overall conclusion that because ES are generally rather complex, we need complex approaches to deal with them – dumbing down the concept from a predictive point of view is silly because it won’t work. I took this to mean we need everything from transdisciplinary systems modelling to multi-faceted policy implementation strategies to mainstream ES in our society. Hooray! More maths.

Steve Polasky was another keynote that always gives good talk. He was adamant that we need to get the biophysical side right first – that is, make the explicit link between environmental degradation and the (quantified) decline in ES. In that sense, I’m a proselytising prophet of Steve’s. Whether that be how much the probability (and therefore, costs) of flooding increases as deforestation occurs, or how much carbon is released into the atmosphere after logging, we need solid, quantified relationships. He said if we don’t get the biophysics right, the economics will necessarily be wrong too. I like it when economists tell us that we’re important (most don’t).

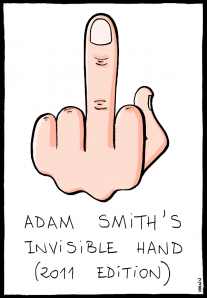

The final keynote particularly worthy of mention was Peter Schoonmaker who spoke during the conference banquet. Although of biology origins, he’s more on the ‘creative’ side of things these days. Regardless, a sharp, funny bloke. He had the crowd giggling constantly as he took the piss out of almost everything academics do. He also passed along some titbits of wisdom (one of which was the problem of the terminology mentioned above). He stated that perhaps the market isn’t the best vehicle for many ES simply because its ‘invisible hand‘ (sensu Adam Smith) doesn’t really make logical decisions, hasn’t really worked that well in practice and cannot possibly lead to a fair and balanced valuation of important public goods like ES. For our sake, don’t let the market (or neo-classical ‘infinite planet’ economists) drive ES trading, or we’ll be proper f*c&@d.

Now to the format of the conference itself. We mere plebeian attendees (i.e., not keynote speakers) were limited to 5-min talks (I gave one on our iREDD concept). Bob explained to me that it was to give everyone a chance to speak without having 20 concurrent sessions and most of the conference reduced to a talkfest (not a do-fest that it was intended to be – see below).

The other component was that two full days were taken up by different ‘workshops’ that participants signed up for on day 2.

Now, it might have been because I hadn’t attended any ESP conferences before, or that I’m not a dyed-in-the-wool ES researcher, or because I didn’t choose the best workshop for my interests, but I don’t think either the talks or workshops achieved their desired goals. While understanding the rationale, 5 minutes isn’t enough to get across anything really important. My view is that we should have had the option to do a longer talk IF we didn’t want to be part of the workshop component.

The workshops also seemed a bit too organic; in other words, I’m not sure 20-40 people per workshop thrown together at the last minute actually achieved much of any use. My view is that pre-determined, hand-picked aims and participants should have been sorted months ago (à la ACEAS, for example), such that a few days could have produced some solid products (like new analyses leading to papers).

One participant I met complained that there were far too many academics there and too few policy makers/social scientists. Sure, if implementation strategy is your aim, he is correct. If getting the ‘biophysics’ right was the aim, then I don’t think there were enough academics. We all like to waffle on about ‘crossdisciplinarity’ and ‘transdisciplinarity’, but let’s face it, that’s bloody tricky, especially over only a few days. In the case of ES, we have huge gaps on both the scientific and policy sides of the fence, so mixing it up too much too early might lead to nothing at all.

My overall conclusion then is a mixed one – I certainly got a lot out of it in that I learnt heaps, but I’m not sure the conference was as effective as it could have been. The next one, scheduled for Bali next year, will be even bigger, so getting the right formula is key. Good luck, organisers.

CJA Bradshaw

-34.917731 138.603034