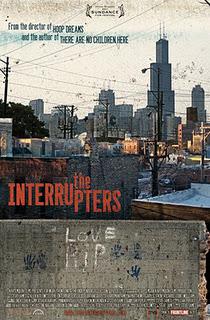

Too many shots of curbside shrines litter Steve James' new documentary, The Interrupters. Too many goddamn shots of goddamn patches of decorated dirt with names and final ages fading up over the soggy teddy bears and perfunctory "R.I.P." scrawls on taped-up cards. James captures so many ambulances racing down Chicago streets to the next act of violence that the vehicles become a sort of active transition, a Kurosawa screen wipe between scenes. With such chaos raging on American streets, it's no wonder so many in the film compare urban Chicago to a war zone, and oddly fitting that the founder of a program to address the uncontrollable waves of brutality is an epidemiologist by trade.

Too many shots of curbside shrines litter Steve James' new documentary, The Interrupters. Too many goddamn shots of goddamn patches of decorated dirt with names and final ages fading up over the soggy teddy bears and perfunctory "R.I.P." scrawls on taped-up cards. James captures so many ambulances racing down Chicago streets to the next act of violence that the vehicles become a sort of active transition, a Kurosawa screen wipe between scenes. With such chaos raging on American streets, it's no wonder so many in the film compare urban Chicago to a war zone, and oddly fitting that the founder of a program to address the uncontrollable waves of brutality is an epidemiologist by trade.Gary Slutkin speaks of the titular Interrupters, a sub-category of his original Cease Fire program, in such technical terms, referring to them as the "initial interruption of transmission." Not, as you may have noticed, the "cure." James is not so presumptuous as to suggest a clear path to more peaceful streets, and his subjects are too battle-scarred to even speculate about such a lofty goal. But it is precisely that temporary aberration, that minor impediment to the unmitigated outbreaks, that sets the stage for a cure. James has always been a filmmaker with a fair hand but a clear point of view, but here he finds a topic without an opposing side. Viewers can form their own opinions about the two basketball prodigies and their families, as well as whether Stevie's crimes should be handled with empathy and study or swiftly condemned and punished for their vile nature. But no one can honestly take a position against CeaseFire, which looks out upon a community where few poor minorities live past 30 and says this cannot continue.

That gives The Interrupters more of a "preaching to the choir" feel than the documentarian's other work, the choir here being practically everyone. Yet James, as ever, makes compelling, intimate drama of social quagmires. If Hoop Dreams is all about the country's misplaced and commercialized values system and Stevie probes the issue of crime and whether one can ever truly reach that crime instead of merely handling each criminal, The Interrupters can only worry about effecting an armistice. It cannot ask similarly high-minded questions because bullets are still flying, and unless the assembly of reformed gangbangers looking to prevent future incarnations of their mistakes can stop them, there won't be anyone left to answer any queries.

As a documentary filmmaker, James excels at finding intensely dramatic stories, and this subject is so immediate that the Interrupters literally have to break up a potential stabbing right outside their office, a situation that spiraled out of control from someone merely talking smack. At a youth transition home, a nearly lethal fight breaks out over a matter of five dollars. Some question Cease Fire using ex-cons and enforcers from the same streets, but one look at how quickly horror can escalate, it soon becomes painfully apparent that only such people can mediate the street war. Even children in the area are so jaded by violence that they need someone who has survived this world to be believable. One interrupter comes to a school designed to help traumatized kids recover and tells them to confide in him. Beside him, a chirpy teacher awkwardly seconds that and says they can talk to her too, but the kids barely even turn their attention to her, looking to unload their secrets and horrors to someone who actually knows. At one point, the director of CeaseFire, Tio Hardiman, meets with some representatives from South Africa to talk about the program, and they express open hesitation about the lack of cooperation between the program and cops, even when Hardiman explains how important it is that the members remain neutral to keep the peace. I couldn't help but find it strange that such trepidation came from citizens of a country that has fresher memories than most of the hostility that can exist between the people and the authorities.

Watching the Interrupters work is akin to witnessing bomb disposal. The altercations that lead to so many deaths in Chicago are often spontaneous and driven by uncontrollable tempers, and to insert oneself into such scenarios takes guts. A recurring "subplot" involves a volatile man who calls himself Flamo, a man driven insensible by his desire for revenge for a slight, willing to die or go to jail and to leave his family without a child and a father. One interrupter, Cobe Williams, deals with Flamo's volcanic rage, clipping the right wires to calm him down without setting off the explosion. Too see Cobe, and the others, placing themselves into such perilous situations is as inspiring as it is suspenseful. Like every free throw shot in Hoop Dreams, every intervention here carries all the more weight for being real.Knowing that every time the Interrupters fail to mediate a feud, someone dies, hits home with brutal drama, Likewise, each success feels all the more joyous for having literally saved a life, maybe even more, as violence begets more violence within mere hours in Chicago, like bacteria multiplying on a petri dish.

But no one commands the audience's attention like Ameena Matthews. The daughter of one of Chicago's most notorious gang leaders, Matthews cleaned up her act and steals the show as the most forceful personality in CeaseFire. On the surface, she looks like she'd be helpless in this line of work, with her short frame and al-amira-covered head. Yet she speaks with a blunt honesty, a wit and righteous fury, that makes her perhaps the most effective member of the Interrupters. Her combination of toughness, harder than the most steely male she confronts, and maternal care makes her trusted by practically everyone, and when she stomps fearlessly into the middle of a group of rough-looking men to admonish them with a boy's obituary, any instinctive fear one might have for such a suicide mission abates when she cows them into shame; James even catches one kid wiping tears from his eyes as she speaks. Ameena is one of those people who will remain in the same neighborhood until she dies, whose impact may never reach beyond that community's borders, yet who articulates and acts upon such a simple goodness that she gives the impression of being able to save the world.

As with James' other films, The Interrupters offers no easy answers, either for the personal stories of constant struggle or the societal issues they embody. With Chicago politicians so desperate to get their districts under control that they beg for the National Guard to patrol city streets, with children as shellshocked with PTSD as returning veterans, barely any hope survives. But some does, and the bittersweet epilogue shows how the actions of these dedicated, reformed criminals, however small, can have demonstrable consequences. Even if they only help one person break the chain of aggression and vengeance, lives will be saved. Chicago will see too many more of those wrenching shrines before the problem is solved, but who could argue that there being fewer of them is anything less than a step in the right direction?