A woman’s suffering face appears above a pair of tortured hands. Birds twitter…her distraught voice whispers…

All I want to do is save the children not destroy them. More than anything I love children. More than anything they need affection, love, someone who will belong to them and to whom they will belong.

And then a man’s voice is heard, “Do you have an imagination?” he asks, and the scene shifts to a well-appointed office where an elegant gentleman is addressing the young woman whose face we have already seen. She is now sitting in a chair and speaks animatedly with him as he continues asking questions and explaining the situation he offers.

Deborah Kerr and Michael Redgrave

These are the first moments of director Jack Clayton’s masterful 1961 film, The Innocents, and they set the stage and tone for a chilling and absorbing tale of bewitchment. Deborah Kerr stars as Miss Giddens, an anxious, fragile-seeming young woman who begins her first position as governess for two orphaned children on a remote estate. Michael Redgrave briefly portrays the gentleman, Miss Giddens’ employer, whose questions and revelations prime and unsettle her before she ever sets foot in the stately home where events will unfold.The story intensifies when Miss Giddens arrives at Bly, a magnificent manor that far exceeds her expectations in its grandeur and beauty. She is “very excited, indeed” to be there and her two “angelic” and precocious charges, Miles and Flora, easily charm her. An earthy housekeeper, Mrs. Grose (Megs Jenkins), serves to ground the excitable governess whose journey proceeds from enchantment to confusion to torment.

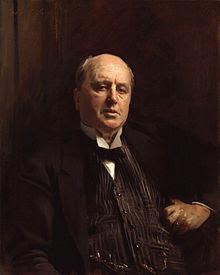

Portrait of Henry James by John Singer Sargent

American novelist Henry James wrote The Turn of the Screw, the source material for this film, in 1898 while living in England in a large rambling mansion. James recorded that the story was suggested to him by an anecdote he heard from the Archbishop of Canterbury. This scrap of a tale concerned young children haunted by the malevolent ghosts of a pair of servants who tried, again and again, to lure them to their deaths.The James novella tells the story of a young governess on her first assignment, the care of two children living in a grand mansion on a sprawling estate. The plot deepens when the young woman, daughter of a vicar, begins to suspect the presence of the malevolent spirits of two deceased servants.

It was several years after the book was published before critics began to wrangle in earnest over interpretation of the story. By the 1920s several had proposed that The Turn of the Screw was less a ghost story and more the tale of inexperienced and high-strung governess who succumbed to hallucinations and madness. A 1934 essay by prominent critic Edmund Wilson dramatically advanced this view. Henry James himself was equivocal about his intentions, and statements he made on the subject have been cited to support both apparitionistand non-apparitionist views.

Fascination with The Turn of the Screw did not wane over the years and it would be adapted from the page to other formats, including opera, the stage and TV as well as film. In February 1950, Peter Cookson’s production of William Archibald’s stage adaption of the James novella debuted on Broadway as The Innocents; Beatrice Straight (Network) starred as the governess.

Jack Clayton and Deborah Kerr on the set

Eleven years later the play would be brought to the screen by British director Jack Clayton (Room at the Top, The Great Gatsby). Though William Archibald was involved, it was Truman Capote who was primarily responsible for the polished screenplay. Capote endeavored to maintain the story’s ambiguity as he felt Henry James had originally conceived it by artfully dodging the central question: Are the ghosts real or are they the fantasies of an unstable governess?Taking the modern view, it’s not difficult to interpret The Innocents as an imaginatively staged depiction of an unsteady young woman’s descent into madness: the film closely follows the increasingly erratic behavior and visible deterioration of Miss Giddens; no one but she actually “sees” the ghosts she claims are present; by the film’s end, even the sensible and supportive housekeeper is at odds with the hysterical governess. And there are many visual clues that the young woman may be projecting her own delusions onto her surroundings. It is no stretch these days to believe that a deranged governess would be capable of utterly terrifying an already frightened child.

But, viewed from another perspective, the tale can also be read as the story of an innocent and inexperienced but well-meaning young woman confronted with the supernatural in the form of malicious spirits. Her fervid determination to save the children in her care from possession could explain her unorthodox behavior. And that is what most people believed when The Turn of the Screw was first published.

Jack Clayton's conjuring of The Innocents leaves viewers to their own conclusions.

Of course, it is Deborah Kerr's finely tempered portrayal of the tortured governess that is the linchpin of this film. With nuanced gesture and bearing, with her expressive voice and bright eyes she breathes her character into skittish-but-determined being. It is Kerr's luminous tour de force performance that makes credible this strange, ghostly tale.

Kerr's portrayal, the supporting cast (with a deep bow to child actors Martin Stephens and Pamela Franklin), Freddie Francis’s atmospheric cinematography, the script of Archibald and Capote, and Georges Auric’s original music all mesh under Jack Clayton’s sure hand to create the acknowledged masterpiece among the several adaptations of The Turn of the Screw.

This is my contribution to the Deborah Kerr blogathon hosted by Maddy Loves Her Classic Films. Click here to learn more.