Otto Preminger's career took a strange downfall, from stylish noirs like Laura to large-scale dramas like Anatomy of a Murder to the notorious flops Skidoo and Rosebud. Mostly, the domineering old studio director seemed hopelessly lost amidst the changing trends of New Hollywood. Preminger's final film, The Human Factor (1979), isn't quite a return to form, but it's at least a respectable swansong for its famous director.

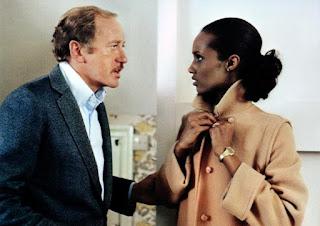

Otto Preminger's career took a strange downfall, from stylish noirs like Laura to large-scale dramas like Anatomy of a Murder to the notorious flops Skidoo and Rosebud. Mostly, the domineering old studio director seemed hopelessly lost amidst the changing trends of New Hollywood. Preminger's final film, The Human Factor (1979), isn't quite a return to form, but it's at least a respectable swansong for its famous director. Maurice Castle (Nicol Williamson) is a mid-level MI6 operative who deciphers intelligence cables from Africa at the behest of his boss Brigadier Tomlinson (John Gielgud). When a routine agency check discovers a security leak, the brass suspect Castle's partner Arthur Davis (Derek Jacobi) and plots an unkind fate for him. The mole is in fact Castle; years ago, he was expelled from South Africa after marrying Black woman Sarah (Iman), and he's disgusted with England's collaboration with their apartheid government. Castle wants out of the double agent game, but when he stumbles across a devious intelligence operation called "Uncle Remus," he's torn between political conscience and family loyalty.

Based on Graham Greene's novel, The Human Factor often resembles the grim literature of John le Carre with its cynical, amoral bureaucrats betraying each other to no clear purpose. Preminger and scenarist Tom Stoppard capture the disconnect between the workaday agents, who nurse dreams of heroism while riding desks, and their commanders who hunt on swanky estates and treat human lives as disposable commodities. In this context patriotism seems effectively meaningless; Castle's aghast that his country not only parlays with apartheid thugs but connives in a scheme to strengthen their power in Africa. Appeals to patriotism and the "Red Menace" ring hollow to Castle; why worry about a government that will disown, or betray you for even perceived failures?

Stoppard's script faithfully adapts Greene's text, yet wrings the story of most of its humor aside from a silly gag about Malteser candies. Factor provides effective moments of ruthless irony, from Castle's superiors casually discussing murder like recounting a football match, to a society matron (Adrienne Corri) who is angrier about a broken statuette than a colleague's death; the sketches of amoral Cold War politics, personified by the odious South African Muller (Joop Doderer), are brief but effectively rendered. But Preminger's direction is rarely more than functional, with unfussy camerawork and deliberate pacing, allowing Castle's dilemma to play out effectively enough, but without truly involving us in his plight.

Nicol Williamson gives a solid performance, making Castle a weary sad sack redeemed by family loyalty and personal morals; it's some of that actor's best work, as Williams dials back his usual scenery-chewing. The supporting cast is largely functional: Richard Attenborough's toothsome counterintelligence and Derek Jacobi's hapless pawn make a good impression, but John Gielgud and Ann Todd's roles are disposable cameos, while Robert Morley's performance consists of waggling his eyebrows at some indignity (or, in one overwrought scene, goggling at a stripper). The weak link in the cast in Iman, the model and future wife of David Bowie, whose stiff deliveries undercut her striking screen presence.

The Human Factor is a perfectly respectable spy film, watchable if never inspired. Perhaps it's unfair to blame Preminger for not fully capturing Greene's novel, which went deeper in its analysis of Castle's character and his uncommon moral dilemmas. Certainly compared to the drek he'd been producing for the past decade-plus, Factor seems like a masterwork in its basic competence. Still, one can't help feeling that a more dynamic director could have turned all of these elements into a great film, instead of one that's merely fine.