The United States used to have a fair economy, where productivity increases were shared among all classes. But since the Republicans seized control of our government about 1980, they changed the economic rules. Now the rich hog most of the increase in production -- resulting in massive income increases for the rich, while workers struggle to just stay up with inflation.

Here is part of a recent report on this from the Economic Policy Institute:

Newly available wage data from the Social Security Administration allow us to analyze wage trends for the top 1.0% and other very high earners as well as for the bottom 90% during 2020. The upward distribution of wages from the bottom 90% to the top 1.0% that was evident over the period from 1979 to 2019 was especially strong in the 2020 pandemic year, yielding historically high wage levels and shares of all wages for the top 1.0% and 0.1%. Correspondingly, the share of wages earned by the bottom 95% fell in 2020.

Two features of the pandemic economy distorted wage patterns in 2020 and led to faster wage growth, especially at the top. One feature was that inflation grew at a subdued 1.2% rate, boosting the average real wage (but not affecting distribution). A second feature was that, as employment fell (the number of earners fell by 1.7 million, or 1.6%) and unemployment rose (to 8.1%), the composition of the workforce changed. Specifically, job losses were heaviest for lower wage workers so the mix of jobs shifted toward higher paying ones, artificially boosting average wages (see Gould) and generating faster measured wage growth especially in the bottom half.

For last year, the data show annual wages rising fastest for those in the top 1.0% (up 7.3%) and top 0.1% (up 9.9%) while those in the bottom 90% saw wages grow by just 1.7%.

This continuous growth of wage inequality undercuts wage growth for the bottom 90% and reaffirms the need to place generating robust wage growth for the vast majority and rebuilding worker power at the center of economic policymaking. See Mishel and Bivens (2021) for the evidence that an erosion of worker power due to excessive unemployment, eroded collective bargaining, corporate-driven globalization, weaker labor standards, new employer-mandated agreements (such as noncompetes), and supply-chain dominance explains wage suppression and wage inequality growth.

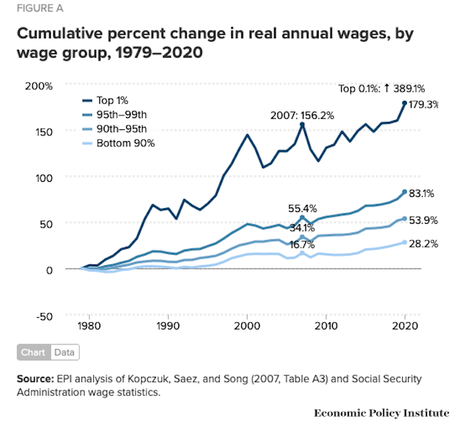

As Figure A shows, the top 1.0% and 0.1% were the clear winners over the 1979–2020 period:

- The top 1.0% saw their wages grow by 179.3%.

- Wages for the top 0.1% grew more than twice as fast, up a spectacular 389.1%.

- The other segments of the top 10% also had faster-than-average wage growth since 1979, up 53.9% and 83.1%, but nowhere near as fast as the wage growth at the top.

- In contrast, those in the bottom 90% had annual wages grow by 28.2% from 1979 to 2020.

This disparity in wage growth reflects a sharp long-term rise in the share of total wages earned by those at the very top: the top 1.0% earned 13.8% of all wages in 2020, up from 7.3% in 1979. That marks the second highest share of earnings for the top 1.0% since the earliest year, 1937, when data became available (matching the tech bubble share of 13.8% in 2000 and below the share of 14.1% in 2007). The share of wages for the bottom 90% fell from 69.8% in 1979 to just 60.2% in 2020.