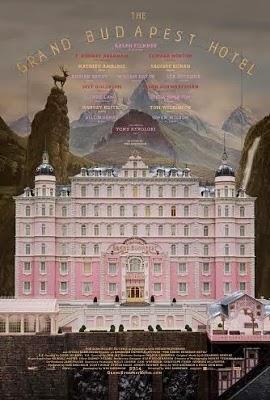

Wes Anderson’s latest, The Grand Budapest Hotel, has bowed to reviews that link the occasionally staggering scale of its production design to the director’s meticulously ordered stop-motion film, The Fantastic Mr. Fox. Certainly the two stand as the most thoroughly crafted works in the oeuvre of a man whose trademark is his fussy attention to detail; in The Grand Budapest Hotel, hotel lobbies, prisons, even Alpine monasteries are created in such lavishly minute precision that the logistics of each impeccably straightened sign, every spotless carpet threaten to divert all attention away from the narrative at hand. In execution, however, the film belongs more with its immediate predecessor, Moonrise Kingdom, as both an unmistakable continuation of its maker’s singular style and an increasingly sophisticated breakdown of it.

Wes Anderson’s latest, The Grand Budapest Hotel, has bowed to reviews that link the occasionally staggering scale of its production design to the director’s meticulously ordered stop-motion film, The Fantastic Mr. Fox. Certainly the two stand as the most thoroughly crafted works in the oeuvre of a man whose trademark is his fussy attention to detail; in The Grand Budapest Hotel, hotel lobbies, prisons, even Alpine monasteries are created in such lavishly minute precision that the logistics of each impeccably straightened sign, every spotless carpet threaten to divert all attention away from the narrative at hand. In execution, however, the film belongs more with its immediate predecessor, Moonrise Kingdom, as both an unmistakable continuation of its maker’s singular style and an increasingly sophisticated breakdown of it.From a narrative standpoint, no Wes Anderson film has ever been this convoluted. Typically, the director’s films spend more time merely introducing the characters and their strictly regimented habits than they do detailing what those people get up to. That is not to say that there is not conflict or drive in Anderson’s movies, but that said conflict typically arises from the intrusion of reality and lived, experienced wisdom upon the myopic headspace of stunted wunderkinder, a forceful denial and eventual acceptance of how ignorant these self-perceived geniuses truly are. But The Grand Budapest Hotel is the first of Anderson’s films in which the outside sources of awakening do not come as a natural course of maturation but from the direct imposition of actively hostile forces. Set primarily during WWII, the film presents a series of nested narratives involving characters whose pluck, intelligence and wit is slowly revealed to be utterly inadequate a defense against forces hellbent on eradicating the old way of things. Anderson routinely presents a sense of style and fashion far removed from the present; The Grand Budapest Hotel hones in on the last moment such modes were considered contemporary and proper before being violently stomped out.

Boasting the densest cast of Anderson’s career, The Grand Budapest Hotel, principally concerns the exploits of Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes), the concierge of the hotel as war looms, and Zero (Tony Revolori), his new lobby boy and protégé. As usual, Anderson establishes these characters with their thoroughly practiced routine, a montage of rushing tracking shots that show Gustave giving or withholding his seal of approval to hotel business and Zero fitting in so quickly it is as if he’d worked at the Budapest forever. The frenzied pace never slows, barreling right ahead into a series of mishaps and adventures that befall the pair, all triggered by Gustave’s predilection for sleeping with the rich, old noblewomen who stay at the hotel. When one of his withered paramours (Tilda Swinton) dies and leaves him a priceless painting her petty family refuses to allow out of their clutches, Gustave and Zero find themselves increasingly at odds with authorities, themselves growing ever more hostile and uncompromising as fascist army regiments take over local law enforcement.

Anderson subsequently launches a series of divertissements, each new subplot offset by its own title card and nestled within earlier plots. The intricate structural order is more than matched by rigorous formal control. This is already a common trait of Anderson’s films, with the camera staring perpendicular at a wall, tracking laterally or along the z-axis and occasionally craning up and down in precise movements. But The Grand Budapest Hotel makes movies like The Royal Tenebaums and The Darjeeling Limited look relatively loose. The characters themselves walk exclusively in motions parallel and perpendicular to the camera; shots of locations echo either in direct matching shots or in long-separated ones that highlight the discrepancies of changing regimes and the natural wear of time; and even pre-existing buildings scouted for the production are given cross-sections that make everything look built specifically for the film. About the only diagonals in the movie are the “ZZ” patterns that clearly stand in for SS banners, but the z’s themselves are rendered in wobbly typeface, as if it took physical effort to push the resistant middle lines of the letters out of a right angle.

This rigid composition not only creates a subtle, aestheticized history of 20th century Europe and its “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” turnovers of leadership, it wryly implicates Anderson’s own penchant for thorough command with fascism’s (and, in some shots of the Budapest in the ‘80s, Eastern Bloc communism) own thought control in the form of approved aesthetics. Yet the film makes a clear distinction between the loving fussiness of people like Gustave, which can be irritating but remains benign, and the anti-beauty outlook of fascists, who seek to control the look of everything to prevent the kind of knowledge and passion that Gustave’s brand of pedantry can ignite. In other words, Gustave values order for its ability to free the mind for other pursuits, while the fascists value it for its ability to seal off the mind.

In one of the film’s best and subtlest jokes, the true moral worth of Dmitri (Adrien Brody), the elder son of Swinton’s dead countess and Gustave’s sworn foe, is revealed less by the ZZ stripe on his coat than how long it takes him to realize that months ago, Gustave already stole the painting Dmitri refused to let him have and replaced it with a pornographic painting. Early on, Gustave notes the painting’s priceless monetary value, but he considers the gift a testament to the countess’s love for him and considers its inheritance a deep honor, but Dmitri simply wants the status of keeping it in the family’s possession, even if he’ll never treat it as anything other than a means of filling up wall space.

The film’s framing device primarily adds just one more level of remove from which to view the action in the form of an unnamed writer played in the scarcely seen present by Tom Wilkinson and in the flashback that begets all the other flashbacks by Jude Law. The writer is a historian of the arcane and aesthetic, piecing together the turbulent 20th-century history of a constantly besieged state through the anecdotal evidence of a long-forgotten institution. This in effect takes Anderson’s filmography to its logical conclusion by making the hotel itself the central character of the film as opposed to any human who walks its halls, but perversely this helps humanize the film. Where movies like Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game (from which Anderson cribs liberally) use their elegant, classical backdrops as illustrations of the cloistered mentality of the dying aristocracy who reside within them, The Grand Budapest Hotel sees in the hotel’s forced modernization a tragedy of lost innocence and change that is imposed, not organic. The film begins with the writer’s younger self arriving at the resort post-communism, but only when it returns to this time period at the end of the film is the erasure of the hotel’s baroque interiors in favor of drab, de-intellectualized “décor” fully felt.

And if the hotel functions as the film’s most obvious symbol of human oppression, its actual characters get their chance to stand out as fascinating, often endearing people. Newcomer Revolori never fails to keep pace with the film’s speed, and as the orphan Zero he brings some of the same bracing energy that Jared Gilman did as Sam in Moonrise Kingdom, occasionally puncturing the other characters’ bubbles of privilege in such a way that their belief in always being right falters. Even smaller, more one-note parts hit their marks, especially Mathieu Amalric’s skittish witness Serge X and Willem Dafoe’s enforcer Jopling, armed with bulldog teeth and a methodical penchant for violence that makes him not so much the live-action rendering of Dafoe’s rat character from Fantastic Mr. Fox but Wes Anderson’s own Bobby Peru.

Naturally, though, it is Fiennes who steals the show with his meatiest role since his mid-’90s emergence, bringing back the acidic edge he displayed in In Bruges but burying it underneath a veneer of ingratiating charm and class. Fiennes’ clipped, terse delivery is perfect for Gustave, official but also capable of great warmth when it slows down to linger on every syllable. The actor’s ferocity has typically been applied in villainous roles of late, but if the main character of the film is the hotel that gives it its title, Gustave’s dropped courtesies and violent displays come out in the defense of his friends (of whom he seems to consider everyone who is not outwardly vile) mark him as one of the few unambiguously heroic characters in Anderson’s oeuvre. Catching up with the old Zero (F. Murray Abraham) reminiscing about Gustave from the hotel he now runs in the man’s memory, the lobby boy’s enduring loyalty stands as a testament less to that of the noble servant but of a man who came from nothing and will never forget the man who treated him, a nameless immigrant child, as an equal. True to the film’s archness, it is this old Zero who tells us, rather than having the film show, the ultimate fate of people like Gustave and his childhood love Agatha (Saoirse Ronan), yet no less indicative of the film’s capacity for humanity is how devastating these calmly related summaries are.