There's something interesting about looking at the shape of a filmmaker's career, what they were doing at certain points, whether there were overlaps or complementary features to be discerned, or perhaps exploratory forays into entirely different areas. It's educational too to note how the extraordinary can cozy up comfortably next to the ordinary. This is something that struck me while looking at some early work by Jack Arnold. In the same year he made the quite extraordinary It Came from Outer Space, he also directed the much more conventional noir/mystery The Glass Web (1953), although that's not to say this latter title is without interest.

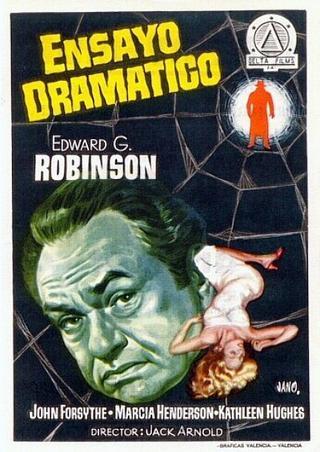

I tend to think of the desert when a Jack Arnold film comes to mind, and The Glass Web opens with a car coming to a stop in just that location. A couple get out and move into the foreground, the wife briefly bemoaning the isolation and discomfort before her husband does away with her and drops her body down an abandoned shaft. Stark and dramatic stuff, but as the camera pulls back it's also apparent that it's a studio set, a mock-up used in the shooting of an episode of a TV show. The actors dust themselves off and the all-important advertising message takes over. The actress who has just been swallowed up by the desert sands is Paula Ranier (Kathleen Hughes), and in some ways this can be seen as a dry run for her eventual fate. Without getting into too many details here, and the consequent risk of spoiling things for those unfamiliar with the film, we're looking at a solid whodunit (although the actual "who" isn't that difficult to work out) with a dark noir heart beating at the center. Everything hinges on a classic triangle involving Ranier, writer Don Newell (John Forsythe) and consultant Henry Hayes (Edward G Robinson), and it's gradually revealed as a complex affair encompassing jealousy, betrayal, blackmail, guilt and humiliation.

As arguably befits a movie concerning itself with entertainment industry figures, the bulk of the action is shot on sets and in the studio, where the characters themselves spent most of their own lives. There are a handful of occasions where events do move outside on location, something I think Jack Arnold usually made good use of, but seeing as the whole story is an insular one centered on a fairly tight group of individuals the internalized feel works quite well. In terms of noir, the movie doesn't break any new ground, focusing on those themes that had become staples of the form by then. I suppose the 3-D shooting was still innovative at the time but I'm not sure it would have brought a lot to proceedings here. Now I've only seen it flat but it doesn't seem like one of those movies where the extra depth would have added much, and the fact there is a short sequence - as Forsythe roams the streets in a despairing mood at the thought of the hole he's dug for himself - where a series of objects are essentially flung at the camera gives the impression the producer felt it necessary to artificially highlight this aspect.

On the other hand, the setting is of interest. The fact TV was very much in competition with, and indeed seen as a threat to, the movies at this stage is of note. Hollywood has always indulged in some inward-looking self-criticism and some of that approach is adopted. There is a particularly cynical view of the role of advertising in TV production - in fact it's rather scornful, with characters commenting how the ads are the most important part of the finished show. Then again, there is also an implied acknowledgment of the power and immediacy of the new medium in the climactic scenes, the culprit carelessly making a confession on a deserted sound stage while the cameras surreptitiously roll and pick it all up. Just as TV in reality could claim to show the viewers events as they happen, so we the audience (and the on screen cops too) get to view this drama unfold via a live feed.

I tend to think of John Forsythe mainly in terms of his television roles, where he was both a familiar face and voice for many years. Having said that, he made a number of memorable big screen appearances too, getting important roles in films by John Sturges and Alfred Hitchcock. His role in The Glass Web has enough complexity to make it satisfyingly unsympathetic and he plays well against the ever impressive Edward G Robinson. By all accounts, Robinson was a cultured man, an trait that often appears at odds with the kind of heavies he was often cast as in the early part of his career, and it's enjoyable to see him as a character with a passion for art and the finer things.

Not for the first time, I find myself writing about a Universal-International movie which remains commercially unavailable, and it pains me particularly to note yet another Jack Arnold title languishing in this fashion. The Glass Web pops up from time to time online, but it's in the usual weak and compromised form. One can only hope that the movie, not to mention a number of others from the same studio, will eventually be afforded a release that allows more people to see it and form their own opinions about its merits.