As a striker, the mighty and lanky Peter Crouch could very well be cast as the Irish maid in a BBC promenade series. His address would sound like West Sixteenth Street (just six blocks north of Cousin Edna’s and two flights of cozy stairs from his drawing room); he would show no interest other than for wood floors, Turkish rugs scattered around and a real fire crackling on the grate. His mother, a Josephine-type, should have taught him to play scales on the piano and a handful of simple exercises from the Italian sketchbook of Clementi.

At training, Crouch would look exhausted as after a long day of bowing and needlework, retreating to the adjoining room to eat his chop and puree of potatoes, whose unpeeled skin had turned a nasty khaki color. What gives Peter the goal-poacher his fearless, lightly mocking, Irish madam look—he would be a Mary (would that be not his name?)—is that, for a tall man like him, he’s amusingly graceful, unexpectedly polite. Peter the character-actor would use honeysuckle scent: to score, to blush and hurry away. His goals for England, all twenty-two of them, just too patriotic, boisterous and go-ahead for soccer financiers to ignore. In his perennial smile, at the very edge of his face, a look to his sidekick at the Britannia stadium. “Was there anything wrong at the bank? You never tell me.”

But then, no matter how many times he’d bob a curtsy, the striker’s job is so undemocratic that Crouch could no longer impersonate the maid. Forget curtains and drapes, and the straw-seated wood chairs; what would make the boy happy, clearly, is cycling.

To plunge into the rumbling of the city cobblestone or the dull, green iridescence of British country roads would make Peter’s smoky eyes swirl or irony and pleasure—a firm thrusting forward of his shaved jaw. And when he receives a through-ball, like against Blackburn early in January, he’d tilt his head to one side, as if in response to high birdcalls of greeting. His confidence on the back of the net—that he would find it, in the vastness of the football park, like a butterfly drifting into a small-leaved boxwood bush—always appears to be pushing aside the offensive, picturesque banality of failure.

In this, Crouch is not a player in the mold of Inzaghi, but he is almost like Kaká (who once preceded him, in 2007, as the Champions League top scorer): he does not want to succeed in a purely egotistical exercise, like the grains of coffee brewing their way impatiently into the espresso pot, but rather like a Victorian cyclist who, while coordinating for a shot, removes the bicycle clips from his trousers, straightens the plaid leg, and then, only then allows himself to pass a large white handkerchief over his shiny forefront.

Which is a way of saying that both Kaká and Crouch perform a kind of slalom skiing, shaking their torso and contracting their throat into a nasal stammer; or that there is only one way to describe their work, and it has to do with a g i l i t y (a charade of guile, ability and total absence of guilt).

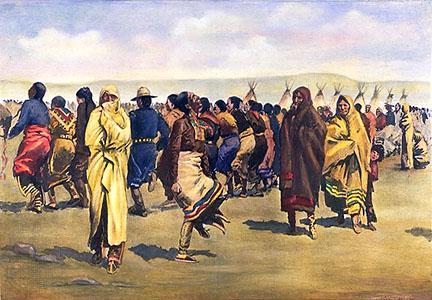

Ultimately, Peter Crouch’s bright, breezy manner comes down to a figure of dance. A hushed, murmuring chorus in front of a full orchestra, or a jazz tune from the jungle period. As a type of striker, with the sunset of David Trezeguet, Crouch has become an unspeakable manufacture himself, leaking through his journey, among other things, a whole history of golf blazers from World War II, money, mud, the English Channel, pennies for a journey to Rome and the episcopal opening in the hands of a priest, a Flemish deathbed scene, and especially an Arapaho ghost dance in 1890s Nebraska that is, perhaps, key to address a Peter Crouch collage in no uncertain terms.

That is the terrifying thing about his craft. The pestiferous swarms of ragged, innocent boys waiting for a new racial dawn. The Irish fought the Italian, and both drank their pints of beer. Something detonated inside the cavern of this mammoth historical body, and now Crouch had grown confused at the edge of the box, as if to ward off a downpour of pebbles, with a great deal of trial and error to score in a contrapposto posture. The umbrage he takes when he misses a chance is a repeated little exercise, know to the Indian tribes during the four days of their circular ghost dance, to establish how much he esteems a goal. ♦