In 1946 four relatively recent American films inspired Italian-born French film critic Nino Frank to pen an article for the August 1946 issue of the newly launched film periodical L’écran française (The French Screen). Titled “A New Kind of Police Drama: the Criminal Adventure,” the article pointed out that these films - The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity, Laura and Murder, My Sweet - seemed more concerned with psychological motivations and undercurrents than crime solving. In his piece, Frank used the term film noir and, ever since, he has generally been credited with coining the expression. However…

Years later the research of Charles O’Brien, a film studies professor at Canada’s Carleton University, and others would show that the termfilm noir was already being used in print in France by the late ‘30s in reviews and articles about particular French films that were emerging at the time.

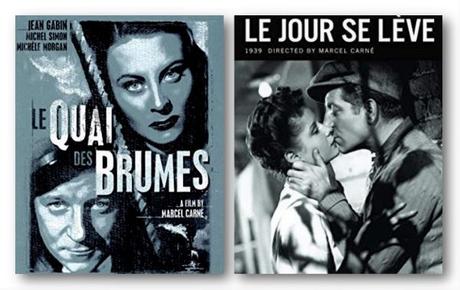

Marcel Carné

Director Marcel Carné (1900 – 1990) was one of the handful of French filmmakers who were making these movies, films of a style that came to be called “poetic realism.” These moody films, awash in light and shadow, fused some of the poignancy of romanticism with a good dose of the fatalism of street-life. Their stories often followed the destinies of tormented characters who, yearning to break out of dead-end lives, fall into tangled love affairs, concoct fanciful schemes, suffer and often die. Today, poetic realist films have come to be considered proto-noir. Marcel Carné would direct two of the best of the genre, Le quai des brumes/Port of Shadows (1938) and Le jour se lève/Daybreak(1939), with French screen legend Jean Gabin (1904 – 1976) starring in both films.When he and Carné began their first film in 1938, Jean Gabin was still in the early years of his stardom. He’d shot to fame in 1935 in Julien Duvivier’s La bandera and had just recently starred in two remarkable films of the poetic realist style, Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko (1937), re-tooled by Hollywood in 1938 as Algiers with Charles Boyer, and Jean Renoir’s classic anti-war film, La Grande Illusion/Grand Illusion (1937).Gabin on the screen is a charismatic everyman,an archetypal Gallic anti-hero. Through most of this era he would portray petty criminals, legionnaires and laborers whose lives have taken a nasty twist or turn and find themselves in a corner, at the mercy of fate.

By the time Le quai des brumes was set to shoot, Carné had gathered the group of creative artists that would form his seminal production team: screenwriter Jacques Prévert, production designer/art director/set decorator Alexandre Trauner (future Oscar winner for The Apartment) and composer Maurice Jaubert. Prévert, a surrealist poet as well as a screenwriter, is credited with complementing Carné’s talent for meticulous composition and staging with his own witty and lyrical way with words, adding “poetry” to Carné’s stylized “realism.” With the arrival of Jean Gabin, this cinematic dream team would be complete.

Michele Morgan and Jean Gabin in Le quai des brumes (1938)

In Le quai des brumesGabin portrays Jean, a deserter from the French colonial army who makes his way to the mist-shrouded port city of Le Havre headed for Venezuela and a fresh start. Adopted by a stray dog en route, Jean waits on the foggy waterfront, commiserating with other disaffected misfits in a rundown bar and meeting beautiful and troubled young Nelly (Michele Morgan). Life in this dreary milieu becomes even more complicated for Jean; he’s fallen in love with Nelly and been drawn into her dangerous world. And so, after finally boarding his ship to freedom, Jean comes back to say one last goodbye. In the end, his parting words to her will be, “Kiss me. Quick. We have no time.” The film’s murky fatalism was not appreciated by the French authorities. The government would later claim that if France lost the war with Germany, Le quai des brumes could take the blame. To this, Carnéwould respond, “you do not blame a barometer for a storm.”In Le quai des brumes the protagonist's fate unfolds gradually, as the tale progresses, but in Le jour se lève the hero's future can be predicted from the outset. The film opens with the sound of a gunshot and the sight of its victim toppling down a stairwell. It is through a series of flashbacks that we learn how Francois (Gabin) came to be a killer and ends up barricaded in his cramped room at the top of the stairs, under siege by the police. Francois is a foundry worker with no prospects, but he is a good-hearted, straightforward man. And then he meets and falls for Francoise (Jacqueline Laurent), an innocent-seeming girl who has dreams of a finer life. When she attracts and responds to the attentions of a slick old seducer (Jules Berry), Francois will be driven to the crime of passion that seals his fate.

Jean Gabin and Arletty in Le jour se lève (1939)

As with Le quai des brumes, this film’s melancholy atmosphere, downbeat storyline and grim ending are powerfully affecting. Gabin’s “beautiful loser” persona provides a resonant core around which Carne’s carefully constructed world without hope can spin. With his sad, knowing eyes, low growl of a voice and world-weary face, impassive and expressive at the same time, Gabin could articulate the state of his character’s heart, soul and mind with a handful of words or none at all.Le jour se lève was released in June 1939, but when World War II began in September French military censors would pronounce it “demoralizing” and the film would be banned.

Time would pass before filmmaking in France could recover from the shattering impact of World War II and the Occupation. When it did, what the war wrought on the country’s psyche would be reflected onscreen. The influence of cinematic trends from around the world would also make an impression, notably American noir and Italian neorealism. From the late ‘40s, the crime films coming out of France would take on a real-world, hardboiled quality epitomized by noirish thrillers like Jacques Becker’s Touchez pas au grisbi/Hands Off the Loot (1954), Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le Flambeur/Bob the Gambler (1955) and expatriate American Jules Dassin’s 1955 film Rififi (slang for “brawl”).

Lino Ventura, Jean Gabin and Jeanne Moreau in Touchez pas au grisbi (1954)

The careers of both Carné and Gabin plateaued in the post-war years. Their final two films together would be La Marie du port/Marie of the Port (1950) and the underappreciated L’air de Paris/The Air of Paris (1954), a boxing story also starring Arletty. Gabin would make two films in 1954; L’air de Paris was the second. The first was Becker’s Touchez pas au grisbi and its huge success would revitalize his career. Gabin would win the Best Actor Award at the Venice Film Festival that year for his performances in both films. And he would go on to make many more movies over the next 20+ years, appearing as George Simenon’s Inspector Maigret in three films of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, and co-starring with Alain Delon and Lino Ventura in The Sicilian Clan in 1969. Gabin would remain a star to the very end, heading the cast in his final film in 1976, his final year, in the befitting role of a "master thief."Marcel Carné’s later years were not so spectacular. There would be no comeback for him. In fact, the director would find himself a target of scorn from certain young critics at Cahiers du Cinema, the influential French film magazine that spawned more than one filmmaker of the French New Wave. Carné would live to the age of 90, but his work past age 45 received little attention. His reputation would rest upon those brooding, evocative films he made from the 1930s to the mid-1940s, starting with Le quai des brumes and climaxing with Les enfants du paradis/Children of Paradise (1945), his masterpiece and the most popular and widely acclaimed French film of all time.

Note: A previous version of this article appeared in the Nov./Dec. 2018 issue of The Dark Pages, the film noir newsletter.

Click here for more entries in the Viva la France! blogathon