Ray is a middle-aged guy with a history of dicey, failed business schemes. Now he’s on the road pitching a super milk-shake machine to restaurants, promising it will boost their sales. Nobody’s interested. (And when eating at these joints, he hates the lousy service and food.)

Ray is a middle-aged guy with a history of dicey, failed business schemes. Now he’s on the road pitching a super milk-shake machine to restaurants, promising it will boost their sales. Nobody’s interested. (And when eating at these joints, he hates the lousy service and food.)

Then he learns that a San Bernardino eatery has ordered eight machines! Curiosity impels him to drive across the country just to see it. There’s a long line outside. “Don’t worry,” he’s told, “it moves fast.” At the window he gives his order. Seconds later he’s handed a paper bag. “What’s this? he asks.

“Your meal.”

“But I just ordered.”

“Right.”

Disoriented, Ray sits on a bench, and bites into his burger. It’s the best he’s ever tasted.

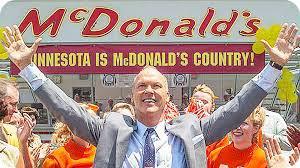

Ray is Ray Kroc. The year: 1954. The restaurant: a solitary local establishment named McDonald’s.

The rest, as they say, is history; told in the movie, The Founder, with Michael Keaton as Ray.

The restaurant’s owners, two brothers named McDonald, give Ray a tour, explaining how, with scientific attention to detail, they’ve created a unique system for delivering food both fast and good. Blown away, Ray hits on the idea of franchising it. The McDonalds say they’d already tried that, and failed, because they couldn’t master quality control from afar. Ray thinks he can, and persuades them to join with him.

The settlement includes removing the McDonald’s brand name from their own restaurant. Eventually, the brothers are driven out of business altogether . . . by competition from a nearby McDonald’s. A text screen at film’s end also notes Ray’s dishonoring a handshake promise of 1% of future earnings.

Hollywood is dominated by people on the political left, with anti-capitalist, anti-corporate bents. Its films reflect this. Maybe strange, since after all they are produced by corporate types making lots of money working for big businesses. Yet they do portray business in a relentlessly negative light.

The Founder is, unusually, a more balanced and mostly positive portrayal of business. Ray is chiefly a sympathetic character. Even when he plays hardball with the saintly McDonalds, we see why he’s kind of right to do so (except for that final bit about the percentage). Though aiming to make money, Ray, and the McDonalds, were impassioned primarily by their vision for giving people excellent products and service. That could not be accomplished without the business earning a profit.

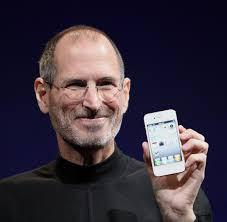

This is the fundamental concept underlying business in general. You profit by giving customers something they value more than what they pay. But that idea gets submerged amid all the anti-capitalist, anti-corporate messaging, infecting even business people themselves

The PBS Newshour recently featured famed glass artist Dale Chihuly and his art-producing “factory.” The interviewer confronted him with criticisms that it is indeed “just” a money-making operation. Chihuly couldn’t answer except by agreeing (only when prompted) that the enterprise, with all its employees, could not continue unless it made money.

Chihuly and creation

He should have said: “What’s created here gives pleasure to people who buy it, own it, view it, and experience it. They value that more than the money they pay (or else they wouldn’t pay it). So yes, we make money, but we make it by making a better world.”

Advertisements &b; &b;