Three’s Company, One’s a Crowd

Unfinished portrait of Mozart by Josef Lange (1789)

Mozart, Verdi, and Wagner – of the three composers discussed so far, the most difficult for the average Joe to swallow in one gulp (if at all) is undeniably Wagner. Certainly his philosophy of life, radical politics, spurious religious musings, and overtly racist tendencies (especially where it concerned the Jewish population of his time), are what give most folks the jitters.

I dare say that for me personally, those issues were not what kept me from appreciating opera’s most demanding genius, as author William Berger liked to phrase it. Specifically, his exacting music and the expansive length of his works were what prevented me initially from enjoying this entirely self-absorbed of individuals.

Once I paid closer attention to his output, however – whether in live radio broadcasts, in the theater in live performances, or on LP records and/or cassettes – while following along with a German libretto and a semi-decent English translation of the same, I finally “got it,” as it were, with respect to Wagner’s dramatic sensibilities. Even as complex a work as Parsifal, which can turn off any number of novices, can seem like child’s play given repeated exposure to the composer’s musical vocabulary and insightful aesthetic.

Some readers may find the following admission surprising but of the three artists mentioned above, Mozart has always been the most challenging for me to grab hold of. At first glance, he may appear to be the easiest to comprehend and to like. Verdi’s music grows on you quickly, as does Puccini’s, who we’ll discuss below. Both these fine composers captivated me from the moment I first heard them. Wagner took a bit of doing, of course, although I was familiar with his concert pieces (including overtures, preludes, interludes, the Siegfried Idyll, and such) from early youth. But Mozart! Oh, how I suffered with trying to get to know him better.

Why was that? Why did Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart cause me so much grief where the others did not? I can’t put my finger on it, except to say that Mozart can be deceptively simple to uninitiated ears. He was, after all, a classically trained and inclined composer (he was good friends with Joseph Haydn), as well as a masterful musician and orchestrator – which basically meant he followed the established musical order of the day, albeit with pre-Romantic era notions.

His works all bear a certain complexity, a breadth, a scope, a chromatic harmonization, along with a predisposition toward symmetry that lesser composers failed to achieve. Yet Mozart’s music is approachable – sublime, according to most scholars, sophisticated and cultured, but always approachable. This seeming dichotomy took a while for me to resolve. In fact, I had the darnedest time overcoming this barrier, a barrier most people come to reconcile with after listening intently to his works on a regular basis.

Most assuredly, after seeing Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus on stage, and then in a successful film version, I was totally swept up in Wolfie’s world. It wasn’t so much playwright Shaffer’s childlike depiction of the Salzburg born composer that so captured my imagination, but the way Mozart’s works came across with such power and conviction – especially Don Giovanni, The Magic Flute, and the Requiem Mass. Thank Mr. Shaffer and his play, and director Milos Forman and his film, for redirecting my focus toward Wolfgang, whom I had previously avoided.

Most listeners new to Mozart soon develop their favorites. There are many operas to choose from, for Wolfgang Amadeus was a prolific purveyor of the different styles of the form – from tragic to comic, from the fanciful to the whimsical. The tragedies (or, if you will, the histories), which in their time were referred to as opera seria (“serious opera”), included such works as Mitridate, Re di Ponto (“Mithridates, King of Pontus”), Il Sogno di Scipione (“Scipio’s Dream”), Lucio Silla, Idomeneo, Re di Creta (“Idomeneus, King of Crete”), and La Clemenza di Tito (“The Clemency of Titus”).

The comedies – with some of them being the most inspired inventions penned by man – featured the charming Bastien und Bastienne, La Finta Semplice (“The Feigned Simpleton”), La Finta Giardinera (“The Pretend Garden Maid”), The Abduction from the Seraglio, his first big hit, and the one-act The Impresario.

Lorenzo Da Ponte (by Pekino) eugeneopera.wordpress.com

For most fans, though, the works that will be forever associated with him are the ones Mozart collaborated on with Venetian-born librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte, i.e., The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi fan tutte (“Women Are Like That”). Da Ponte, an amazingly versatile talent (and an inveterate womanizer) who knew the infamous Casanova personally, as well as spoke several languages fluently, was a genuine Renaissance man. Among the numerous posts he held during a richly varied career, he eventually wound up teaching Italian literature at Columbia College in New York.

Notwithstanding the above association, Mozart’s last opera, The Magic Flute, co-written with impresario, theater owner, and fellow Freemason Emanuel Schikaneder, who provided the story and structure, managed to straddle both the comic and dramatic in fairly equal proportions, in this, his final statement on the subject. The richness of his musical language and the profoundness of his observations about the human condition lead one to conclude, without the slightest exaggeration, that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was indeed the Shakespeare of the operatic stage.

There’s No Business like Show Business

The last, but certainly not the least, of our operatic hit-makers is one of the most beloved. Giacomo Puccini was no doubt destined for operatic greatness. By the time of his birth in December 1858, there had been five previous generations of Puccinis, all of them composers and/or musicians of one sort or another. Sadly, little Giacomo turned out to be the last of that distinguished line.

In his later years, Puccini wrote of a dream he once had as a youngster, where after traveling some distance to see a production of Verdi’s Aida, he collapsed in his hotel room from sheer exhaustion. In his dream, God came down from heaven and touched him lightly on the shoulder, promising him great success if he wrote for the theater. “Mind,” the composer said, recalling the Almighty’s admonition, “Write only for the theater!” Needless to say, Puccini took the Lord at His word: he became a dutiful man of the theater.

Giacomo Puccini (gramophone.co.uk)

Solidly middle class, the Puccini clan lived in a remote region of northern Italy where hunting and fishing were the main activities, but it was close enough to the principal city of Milan that he could enjoy music and theater, in addition to (ahem) other entertainment. Yes, dear readers: Puccini was another one of those incorrigible ladies’ men – and it was a good thing, too! For no other Italian composer of his era was as attuned to the feminine mystique as he was.

A quick perusal of Puccini’s complement of female heroines tells the tale: the worldly, free-loving Manon Lescaut; the tubercular seamstress Mimi from La Bohème; the quintessential opera diva Floria Tosca; the former geisha-turned-loving mother Cio-Cio-San from Madama Butterfly; the cloistered, suicidal nun Sister Angelica; the spoiled-rotten daughter Giannetta from Gianni Schicchi; and the loyal slave girl Liu from Turandot.

All of them have tugged at our collective heart strings: we smile at their generosity of spirit, we laugh at their comically exaggerated antics, we frown at their willful ways, and we cry at their tragic fate — while applauding them wildly at the final curtain. They were all the creation of one man: Giacomo Puccini, from first to last an artist of considerable genius.

When he was a young music student, Puccini and several of his colleagues, among them the future composer of Pagliacci, Ruggero Leoncavallo, lived the proverbial bohemian life. Their struggles for survival, their battles with hunger and the elements, with having to find enough money to pay the overdue rent and other innumerable privations, were immortalized in his timeless classic of young love, La Bohème.

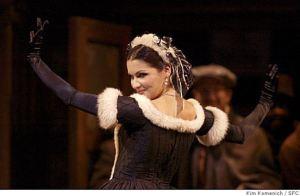

Here is Musetta’s Waltz from Act Two of the opera. It’s a marvelous tune, one that’s attracted an infinite number of beauty-pageant contestants from time immemorial. But don’t let that stop you from enjoying Musetta’s Waltz, sung by the Russian soprano Anna Netrebko: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NQ_1N8j4bJ0

Anna Netrebko as Musetta (sfgate.com)http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NQ_1N8j4bJ0

Puccini’s other great passion – smoking cigarettes – inevitably cost him his life. He developed cancer of the throat, and bravely endured experimental treatments in Belgium to combat it, all the while busying himself with trying to complete what would turn out to be his final work for the stage, the opera Turandot, one of the grandest of grand operas.

Unfortunately, time ran out for the composer. Puccini passed away in Brussels of a heart attack on November 29, 1924, at the age of 65. His body was transported back to Italy for burial at his estate near Milan. On April 26, 1926, his unfinished Turandot had its world premiere at the Teatro alla Scala.

Another composer had been assigned the unenviable task of completing it. However, at about the halfway mark in Act Three – the exact spot where Puccini stopped composing – the conductor of the event, the formidable Arturo Toscanini, one of Puccini’s oldest and dearest friends, put down his baton, turned to the audience and announced, in a voice choked with emotion, “It was here that the Master laid down his pen,” whereupon Toscanini abruptly left the podium. The press later reported that the crowd had filed out of the theater in absolute silence.

Puccini in his later years (gluxus.com)

With Puccini’s passing, opera itself began to draw its own last dying breath. Certainly after him, no other Italian composer – and very few foreigners of any nationality – would be able to regale their fans in the same way as the Fab Four of Opera had.

It would be left to Broadway’s Great White Way to take musical theater down a completely different path. But that’s fuel for another story…

(End of Part Four)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes