I love books, and there is a small cluster of core books that accompany me on my journey to painterly enlightenment which I would heartily recommend to other painters. These are the books I turn to again and again: reference books, philosophical books, history books and diaries which have profoundly shaped my learning and my views on art. If you need to be your own teacher for the moment, there are some wise dudes you can depend on for guidance.

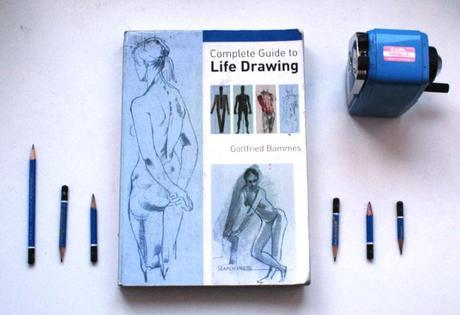

Gottfried Bammes: Complete guide to life drawing

This book has consumed me since I first met it, and travels the world with me. Herr Bammes, who taught in Dresden, has a clear way of describing the human body in simplified volumes and muscle groups that help one think structurally about the body. Rather than overwhelming yourself by starting out with hard-core anatomy, working through Bammes’s guide will help you ease into more complex anatomical study by giving you a broader understanding upon which to hang such knowledge. He begins with exercises on proportion and movement, setting a firm foundation of both accuracy and expressive liveliness. From here, he explains the parts of the body in greater detail, with many of his own examples reducing the forms to blocks in perspective. His diagrams on knees and feet in particular are works of teacherly genius. Bammes diagrammatically explains the mechanics of the bones and muscle groups, as well as reducing their construction to simple linear frames. Right from the beginning he gives the student a firm way of indicating a solid foot, which when rehearsed and developed only serves to cement the structural understanding.

Says Bammes (2010: 222), ‘If skull drawing is not practised as if it were architecture, with a perpetual ordering of primary and secondary aspects—if it is not done with awareness—it will degenerate into nothing more than clever copying and will not provide any gain in knowledge or vision.’ Yet he (2010: 10) never loses sight of why we demand so much of ourselves: ‘When we draw people, we are growing towards others and ourselves and we reveal things that were lost before to our fleeting glances and inaccessible to our experience.’

The margins of the book are peppered with a fine selection of master drawings, including those of many lesser-known German draughtsmen, while all examples are drawn by the elegant and controlled hand of Bammes himself. I cannot recommend this book enough. I’m still working slowly through it, using it as a companion to all further anatomy study, and revisiting earlier chapters again and again.

Bammes, Gottfried. 2010. Complete guide to life drawing [Menschen zeichnen Grundlagen zum Aktzeichnen]. Trans. Cicero Translations. Search: Kent.

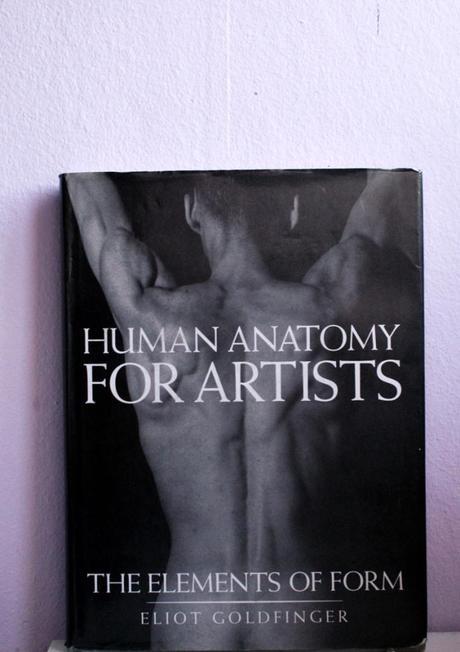

Eliot Goldfinger: Human anatomy for the artist

This book is an investment, but a good anatomy book is a necessary tool in your belt if you’ve any real interest in the figure. The delightfully named Goldfinger turns his Midas touch to one bone, one muscle at a time, displaying many angles and overlaps and cross-sections. The text explains function, origin and insertion and many other enlightening aspects of each part, but clear drawings illustrate most of the information. These drawings are accompanied by some photographs of an extremely ripped model, to help locate things under the often-obfuscatory surface of flesh. And several straight-lined diagrams explain difficult-to-conceptualise mechanics or simplifications to help remember the main features of a part.

Goldfinger (1991:. 64) encourages a deep understanding of the figure, not just a grasping after surface variations:

‘During complex actions, note the sequence of the contraction and relaxation of the numerous muscles that are functioning. Observe the action, visualise the skeleton deep in the body and what changes are taking place at its joints, then determine which muscles are working.’

This book is an artist’s dictionary. It will also make you sound clever at parties because you will learn a lot of scientific words.

Goldfinger, Eliot. 1991. Human anatomy for artists: The elements of form. Oxford University: Oxford.

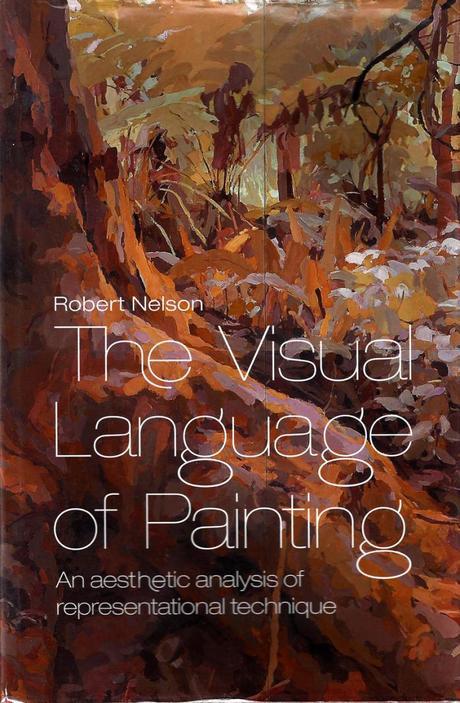

Robert Nelson: The Visual Language of Painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique

This book has affected me deeply. It made me appreciate how genuinely scholarly painting and drawing could be, while never losing sight of how physical and sensual it is. Nelson’s (2010: 27-28) project is an admirable one of finding a way to unite the studio and academic practice:

‘I would like to see a philosophy of technique which positions technique as the necessary correlate of poetic vision and the basis of visual language, a philosophy which is non-instrumental and anti-mechanistic. I would like to cultivate a discourse which deals with the motivation, the aesthetic benefits, the almost physiological processes of perception, but also the wilful staging, the theatricality of expressing what happens in the mind, the eye and the hand. … The project, if it could be pursued as I hope to demonstrate, would bring studio technique into the heartland of scholarship in the humanities.’

Nelson writes knowledgeably and generously on delightfully mundane topics, validating painterly excitement at painterly preoccupations: on drawing, on composition, on edges, on shadow. Yet he is able to articulate better than most artists what it is that is so thrilling and relevant about these topics: that painting, not merely writing, may be ‘a vehicle for discourse’ (2010: 10); that ‘drawing, in short, is a deliberateness in seeing which declares itself and argues what it wants to define’ (2010: 55), that it ‘manifests your will to possess intellectually’ (2010: 54).

Every time I pick this book up I am filled afresh with new thoughts directly related to the practice of painting, and intellectually energised as well. We can speak clearly, intelligently and unashamedly about the physical and visual aspects of our work, not just about concepts and symbols and statements. For our work does make investigations by means other than words and symbols, and we would do well to argue for the standing of our visual language.

Salvador Dali: Diary of a genius, an autobiography

The diaries of artists are pure gold. Sometimes they divulge their painting secrets, or elaborate on what, specifically, drives them wild about Rubens, or, as in the case of Dali, bestow an entire philosophy upon you. ‘The uniform is essential in order to conquer,’ Dali (1966: 53) proclaims (Dali only makes proclamations. This is in itself a lesson). ‘Throughout my life, the occasions are very rare when I have abased myself to civilian clothes. I am always dressed in the uniform of Dali.’ And to a young man who is willing to accept the sort of despicable, filthy, poverty-stricken life an artist is expected to lead he admonishes with devilish wisdom (1966: 53-4):

‘If you want to eat beans and bread every day, it will be very expensive. You must earn it by working very hard. On the other hand, if you can get used to living on caviar and champagne, it doesn’t cost a thing.’

He smiles stupidly and thinks I am joking. …

‘Caviar and champagne are things that are offered you free by certain very distinguished ladies, wonderfully perfumed and surrounded by the most beautiful furniture in the world. But to get them, you must be quite different from the you who comes to see Dali with dirty fingernails, while I have received you in uniform.’

Dali, Salvador. 1966 [1964]. Diary of a genius, an autobiography. Trans. Michel Déon. Picador: London.

Ernst H. Gombrich: The story of art

When you find this ubiquitous book for a couple of quid in a charity shop, buy it immediately. The Viennese-born, Oxford-dwelling, self-professed non-art-historian wrote this book as honestly and clearly as he could, intending it to avoid the hormonal scorn of the teenage audience for whom it was written, and to whom the book intends to introduce art. The premise of this book is that ‘there really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists’ (1972: 4) and that a history of artists thus reveals a saga of cosmically different aims and forces. Gombrich trips lightly and eagerly over his words, ever able to see merit in the visual works of humankind. It’s impossible not to get caught up in his enthusiasm for and appreciation of our varied collective efforts. Everything has its place–and time, rather than linearly measuring our progress, merely greets us with different demands. Learn to truly appreciate art, to discover the joy of paintings and sculpture and architecture, and instantly become ten times smarter.

Gombrich, E. H. 1972 [1950]. The story of art. Twelfth ed. Phaidon: Oxford.

John Dewey: Art as experience

This surprising book throws heavy punches. It clearly expresses the things about art that make you angry and explains why they should go away. It could only hurt your foes more if you socked them in the face with it.

First of all, Dewey discusses the mysteriousness of art—its detachment from life, its artificial isolation in museums, its role of showcasing imperial conquests. Rather than being removed from our experience, he argues, art should be in the thick of it: it should be the very substance of our lives. ‘The times when select and distinguished objects are closely connected with the products of usual vocations,’ he argues (1934: 6), ‘are the times when appreciation of the former is most rife and most keen. When, because of their remoteness, the objects acknowledged by the cultivated to be works of fine art seem anemic to the mass of people, esthetic hunger is likely to seek the cheap and the vulgar.’ If we live in a world of cheap thrills and throwaway entertainment, it is because we have been told we can’t have nice things, locking them away as mysterious artefacts of Art.

Dewey also addresses the strange introspective tendencies of contemporary artists. Not only has art been excluded from ordinary experience, but ‘because of changes in industrial conditions the artist has been pushed to one side from the main streams of active interest’ (1934: 9). The non-integrated modern artist is forced to turn to ‘a peculiar esthetic “individualism”’—relying on ever more obscure ‘self-expression’ (1934: 9). Art becomes even more foreign to ordinary experience. Seriously, is anyone reading this book?

And in case you were willing to defend art’s reincarnation as ‘self-expression,’ Dewey has a few sucker-punches lined up for thoughtless paint-spilling, which he considers little more than ‘discharge’ (1934: 62):

‘To discharge is to get rid of, to dismiss; to express is to stay by, to carry forward in development, to work out to completion. A gush of tears may bring relief, a spasm of destruction may give outlet to inward rage. But where there is no administration of objective conditions, no shaping of materials in the interest of embodying the excitement, there is no expression. What is sometimes called an act of self-expression might better be termed one of self-exposure; it discloses character—or lack of character—to others. In itself, it is only a spewing forth.’

Dewey demands serious and honest thought from artists, and sees their intellectual processes as differing only in emphasis from that of the scientist (1934: 15). The main difference between the intelligent artist and the scientist is her medium: rather than working in abstracted symbols, ‘the artist does his thinking in the very qualitative media he works in, and the terms lie so close to the object that he is producing that they merge directly into it’ (1934: 16).

The only question left to ask is, how did art fester into the hideous mess presently molesting our eyes while this book has been kicking around for eighty years?

Dewey, John. 1934. Art as experience. Minton, Malch & Company: New York.

David Galensen: Old masters and young geniuses: The two life cycles of artistic creativity

If you are discouraged at not yet being famous, this soberly-written book ought to give you a good dose of optimism and dispel a lot of silly ideas about creativity and inspiration. Instead of resorting to wild speculation, Galenson has spent years doing research into the way artists work and describes two broad approaches. He calls them the ‘conceptual’ (or deductive) and the ‘experimental’ (inductive). In identifying whether you are good at quickly synthesising ideas and conceiving entirely new ones out of them, or whether you are consumed by a single idea which drives all your investigations, or rather somewhere along this spectrum, you will free yourself from expectations and judgements that don’t actually apply to you. And that means you can just get down to work instead of taping brazen Picasso quotes to your wall.

‘Aptitude and ambition are more important factors in allowing people to make contributions to a chosen discipline than the ability to think and work in any particular way, either deductively or inductively.’ (2006: 166).

Galensen, David W. 2006. Old masters and young geniuses: The two life cycles of artistic creativity. Princeton University Press: Princeton.

Kenneth Clark: The nude: A study of ideal art

I am steadily drawing my way through this book. Not all nudes were created alike, and as you progress through this book you will gain an appreciation for the subtleties of purpose that the bared human form has risen to meet. ‘The English language, with its elaborate generosity,’ Clark (1985: 1) gushes at the outset, ‘distinguishes between the naked and the nude.’ From the outset, he is at pains to emphasize that the nude, rather than being the very essence of art, is ‘an art form invented by the Greeks in the 5th century B.C., just as opera is an art form invented in 17th-century Italy’ (1985: 3).

Our artistic tradition is heavily shaped by the elegant foundation laid by the Greeks, and not just through their mythology. I have been amazed, however, at how the gods and goddesses effortlessly step from one role into another—with lion-skin-wearing Hercules transforming into the honey-eating-from-inside-the-lion Samson, with Apollo and David interchangeable youthful heroes in the mind of Michelangelo. But beneath the stories themselves lies the earthy Greek philosophy which embodies every idea and passion in human form (1985: 20; 21):

‘The Greeks attached great importance to their nakedness. … It implies the conquest of an inhibition which oppresses all but the most backward people; it is like a denial of original sin.’

Of course, the other half of our heritage is the Judeo-Christian tradition, and the nude suffers painfully under the Christian worldview, disrupted though never entirely abandoned (1985: 203): ‘While the Greek nude began with the heroic body proudly displaying itself on the palestra, the Christian nude began with the huddled body cowering in consciousness of sin.’ The awkwardness of our artistic tradition seems to rest on this unhappy marriage of earthy and heavenly philosophies.

Don’t expect a dry historical account of statues, though. Clark winds back and forth, attending in turn to Apollo and Venus, energy and pathos, ecstasy and the grotesque. The book is full of pictures to copy in the absence of life models, and will open your eyes when you return to the gallery to dutifully copy from the antique.

Clark, Kenneth. 1985 [1956]. The nude: A study of ideal art. Penguin: London.

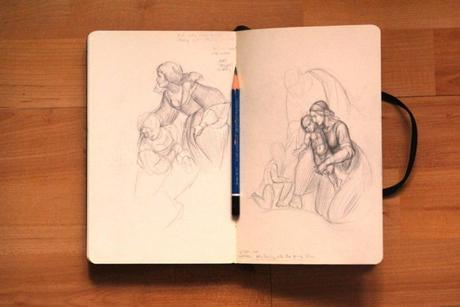

Sketchbook

Words, words, words. Time to draw.