(reproduced from The Conversation)

(reproduced from The Conversation)

Of all Australia’s wildlife, one stands out as having an identity crisis: the dingo. But our recent article in the journal Zootaxa argues that dingoes should be regarded as a bona fidespecies on multiple fronts.

This isn’t just an issue of semantics. How someone refers to dingoes may reflect their values and interests, as much as the science.

How scientists refer to dingoes in print reflects their background and place of employment, and the Western Australian government recently made a controversial attempt to classify the dingo as “non-native fauna”.

How we define species – called taxonomy – affects our attitudes, and long-term goals for their conservation.

What is a dog?

Over many years, dingoes have been called many scientific names: Canis lupus dingo (a subspecies of the wolf), Canis familiaris (a domestic dog), and Canis dingo (its own species within the genus Canis). But these names have been applied inconsistently in both academic literature and government policy.

This inconsistency partially reflects the global arguments regarding the naming of canids. For those who adhere to the traditional “biological” species concept (in which a “species” is a group of organisms that can interbreed), one might consider the dingo (and all other canids that can interbreed, like wolves, coyotes, and black-backed jackals) to be part of a single, highly variable and widely distributed species.

But the “biological” species concept used to name species came about long before modern genetic tools, or even before many hybrid species were identified by their DNA (such as the “red wolf,” an ancient hybrid of gray wolves and coyotes found in the southeastern United States).

Few people would really argue that a chihuahua, a wolf, and a coyote are the same species. In reality there are many more comprehensive and logical ways to classify a species. In our latest paper we argue that a holistic approach to defining species is essential in the case of the dingo and other canids.

Our work shows conclusively that dingoes are distinct from wild canids and domestic dogs based on many different criteria.

Truly wild

The first criterion is that dingoes are wild animals, and live completely independent from humans. This is fundamentally different to domestic, feral, or wild dogs, which must live near human settlements and rely on humans for food and water in some way to survive.

Yes, the dingo might have arrived in Australia with humans, and we know that Aboriginal Australians have had a close relationship with dingoes following the latter’s arrival. But neither of these observations excludes dingoes from being wild.

For example, a relationship with humans does not constitute the rigorous definitions of domestication. Consider the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), which was also introduced to Australia by people and are now free-ranging: they are also not considered to be domesticated. Neither are wild animals such as birds that we feed in our backyards domesticated simply because they are sometimes fed by us.

Ecological role

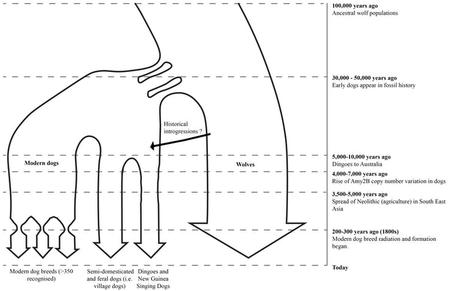

In fact, dingoes have been living wild and independently of humans for a very long time — they have a distinct and unique evolutionary past that diverged some 5 to 10 thousand years ago from other canids. This is more than enough time for the dingo to have evolved into a naturalised predator now integral to maintaining the health of many Australian ecosystems.

Dogs do not have the brain power or body adaptations to survive in the wild, and they cannot play the same ecological role as dingoes. From this ecological perspective alone, the two species are not interchangeable. Dingoes are Australia’s only large (between 15-20 kg), land-based predator, and as such play a vital role in Australia’s environment.

Shape and size

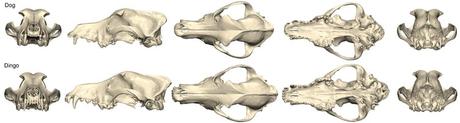

Viewed alone, the overall shape of the body and skull does not easily distinguish wild canids from dogs, mainly because of the sheer diversity among different breeds of domestic dogs.

But there are some important body differences between free-ranging dogs and dingoes, mainly in the skull region (as shown here and here).

Behaviour

Dingoes (and other truly wild canids) have some fundamentally unique behaviours that set them apart from dogs (although like shape, there are often exceptions among the artificial dog breeds). For example, dingoes have significantly different reproductive biology and care-giving strategies.

There are also differences in brain function, such as in the way the two species solve problems, and dingoes and dogs communicate differently with humans.

Genetics

While dingoes and dogs obviously share an ancestral relationship, there is a lot of genetic data to support the distinction between dingoes and dogs.

While dingoes share ancestry with ancient Asian dogs from 10,000 years ago, the dingo has been geographically isolated from all other canids for many thousands of years, and genetic mixing has only been occurring recently, most probably driven by human intervention.

Since the 1990s, genetic markers have been in widespread use by land managers, conservation groups, and researchers to differentiate dingoes from domestic dogs.

What’s at stake?

Even acknowledging the dingo’s uncertain and distant past, lumping dingoes and dogs together is unjustified.

Labelling dingoes as “feral domestic dogs” or some other misnomer ignores their unique, long, and quintessentially wild history in Australia.

Inappropriate naming also has serious implications for their treatment. Any label less than “dingo” can be used to justify their legal persecution.

Further loss of dingoes could have serious, negative ecological consequences, including potentially placing other Australian native animals at increased risk of extinction.

Bradley Smith, CJA Bradshaw, Euan Ritchie, Justin Adams, Kylie Cairns, Mathew Crowther