Laptops had been around and fairly common since the early 1990s. The nature of computing technology was such that laptops were somewhat more expensive than a desktop or tower model of equivalent power. But by the mid-2000s laptops had become cheap enough that even I could afford a nice one. I opted for a 15 inch Apple PowerBook G4. Given that I had two decades of work sunk into the Macintosh platform I had little choice but to continue down that line, though I’d used Windows machines, both laptops and desktops, in various consulting and professional gigs.

I had several reasons for going with the PowerBook G4. For one thing, I really had no love for a big machines and I was now doing some work where it could make use of a nice laptop for making presentations. Moreover, since it was only the processor that had gone bad on my G3 machine, I could keep the LCD monitor and hook it up to my PowerBook.

Two monitors! Whoo hoo! Two screens at once. What’s not to like?

* * * * *

Caveat: This is one of those posts that just grew and grew beyond my original expectations. It all seemed so simple in my mind. But I decided that I really needed to talk about learning to use a mouse and related matters, and that turned out to take a bit of doing.

My G4 Laptop and Two Screens

I ordered the G4 online and had it shipped to my friend Steve, who installed some software on it and then came to my place where he transferred my data files from the G3 to the new G4. This is the first time I’d hired an expert to make the transfer for me. And I’m glad I did.

There was nothing to transfer from my NorthStar to my first Mac. For each subsequent Mac transfer simply meant loading a bunch of floppies into the new machine. But the PowerBook didn’t support floppies. So I had to make sure I’d loaded all my floppies onto the G3’s hard drive. I’m sure I got most of them, but not all of them.

Steve ported this and that from the G3’s hard-drive and I was up and running on my new laptop, with two, count ‘em, two screens.

That made a tremendous difference in how I worked. By this time I was actively cruising the Internet and often had a browser open to several web pages. When writing I often had more than one document open: the document I was working on, one or more satellite documents containing notes and text, and I often had two windows open on the same document. I might have had a graphics program running as well.

Keeping track of three, four, five or more windows on one screen was a bitch. Two screen made things much easier – not ideal, mind you, but more manageable. The old LCD monitor only lasted a year or three before I had to replace it. I got a 20-inch Apple Cinema monitor, which was much larger than that old monitor (which was 13 or 15 inches, I forget which). I was a happy camper.

Here’s that setup:

You see the Cinema monitor up above and the PowerBook below. As for the two creatures on the PowerBook – that’s Sparkychan on the left and Gojochan on the right – there’s an interesting story there, but it would be something of a distraction for me to recount it here. Let’s just say that that photo was one of many I took in the process of telling a story to a couple of very young girls in Japan, daughters of one of my online friends (this post discusses that adventure in somewhat more detail: The Freedoniad: A Tale of Epic Adventure in which Two BFFs Travel the Universe and End up in Dunkirk, New York).

But that dual monitor setup, as useful as it proved to be, also raises a very important issue, one I haven’t yet touched upon in this series: How do you assimilate a computer to your body? The issue has fairly profound psychological and philosophical ramifications. Right now, though, I want to discuss the practical problem, which is:

How do I move my hands and eyes in order to get things done?

Typing and Mousing

Let’s backtrack a little, to the days before I even dreamt that one day I’d own my own computer. During the summer after my senior year in high school I took a six-week course in touch typing, knowing that I’d be writing a lot of papers in college and typing would be essential. And I did (write a lot of papers) and it (typing) was (essential). But there’s more – there always is.

When, as an undergraduate, I took a course in computer programming how did I interact with the computer? Typing. In some cases the keyboard was connected to a cardpunch so that the result of my typing was a stack of cards that I then had to submit to the computer center to have the program run. In other cases the keyboard drove a paper tape machine, which spit out a paper tape with holes punched in it. I don’t quite remember what I did with the tape; perhaps I just fed it into a tape reader next to the punch. But it doesn’t matter.

Typing’s the point. That’s how I interacted with the computer, which happened to be an IBM mainframe located in a different city. Well, my NorthStar Horizon was right there on the desk in front of me, but I interacted with it through typing as well. I type on the keyboard and see the results on the CRT screen.

Typing and screens remain a constant across all my machines. But when I got my first Mac I had to deal with a new interface device, the mouse. This wasn’t difficult, but it took several days or perhaps a week for it to become comfortable. This has two aspects: 1) physically moving the mouse while “dragging” and “clicking” and 2) getting used to a new mapping between visual space and motor-kinetic-haptic space.

The mapping between visual and tor-kinetic-haptic space is not “wired in”, but we learn it very early in life, in roughly the middle of the first year. Until that happens an infant can be waving her hand in front of her face but not associate the moving object she sees with the sensations muscular effort and hand motion. These exist in different sensory motor spaces. Since, however, the infant is ever living in those spaces and the brain is maturing rapidly, these spaces become mapped together – call it visual-motor-kinetic-haptic space, VMKH) at a very young age.

That basic mapping, however, is violated in using the mouse. One’s muscles are moving the mouse at one place in VMKH space, but the visual action is located at a different place in that VMKH space. In order to become fluent in using a mouse you have to create a new mapping between visual and motor-kinetic-haptic space. That takes awhile.

What is it that the mouse is moving in visual space? Basically, anything on the screen. The most basic of these objects is the cursor, which is simply a pointer. If you’re working in a word processing document, you can move the cursor around on the page to select where you want to type or to select chunks of text to be cut from the document and either thrown away or moved elsewhere. And so forth and so on.

But this document exists in a window on the screen. You can “grab” the window with the mouse and move it around on the screen, and even make it larger and smaller, etc. All of this is obvious to anyone who’s spent time working with a computer, but it was new to me back in 1984 when I got that first Mac. So, arm hand and fingers move the mouse in kinetic and haptic space and that drives the motion of the cursor, or some other visual object in the visual space of the computer screen.

And this brings us back to where we were just a moment ago: How does one deal with having two monitors? It’s one thing to glory in having two monitors (or even more – there’s a well-know photo of Al Gore with three 30” monitors – but why stop at three?) because it allows you to have so much stuff on view at one time. But…

Moving Around: Two Screens

… how do you work with them, how do you move around them? The same way you do with a single screen, but you’ve got to “tell the computer” how you want it to work.

On the one hand there is a physical connection between a monitor and the processor. That gets signals back and forth between them. Somewhere the processor has a map of the monitor’s 2D surface; call it the screen map (SM). Somewhere else the processor has a bunch of stuff that’s destined to appear on the screen; call this information ready to display (IRD). The processor needs a map from IRD to SM in order for the screen display to be effective. Think of it something like this:

If we’ve got two screen screens, then we need two screen maps. Keeping in mind that I’m just making this up as I go along, calling on my sense of the principles involved, we then map the Information Ready to Display to these two Screen Maps, each projecting to a different display. No big deal.

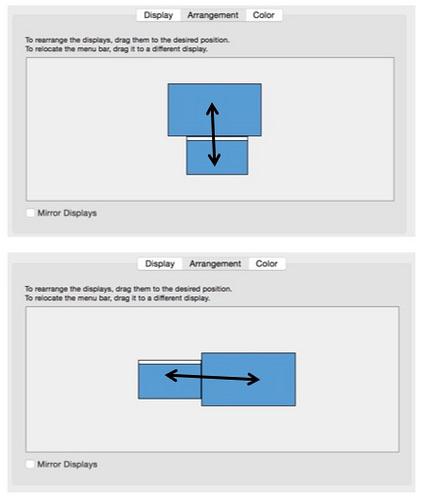

Where things get tricky is with the mouse. Remember it? It’s moving the cursor around on screen. Now it’s moving the cursor across two screens. How does it get from one screen to another? The user needs to tell the computer how that’s supposed to go. So the Mac OS has a preferences panel where you do this.

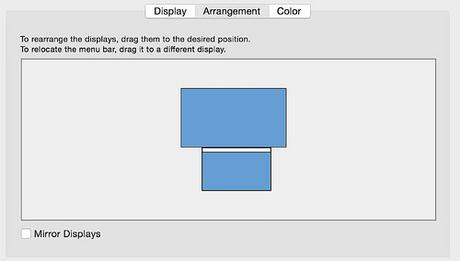

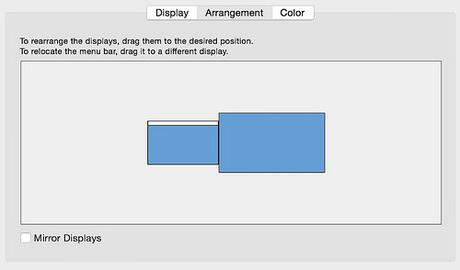

Here are two possible arrangements:

And if you think about it, what those diagrams are about is NOT the physical location of the two (or more) screens with respect to one another, but about the logical path of cursor movement from one screen to the other:

If you choose the upper arrangement, then you move the cursor, or other visual object, from one screen to the other across the top edge of one and the bottom edge of the other. If you choose the bottom arrangement, then you are moving the cursor across the left edge of one screen and the right edge of the other.

If you choose the upper arrangement, then you move the cursor, or other visual object, from one screen to the other across the top edge of one and the bottom edge of the other. If you choose the bottom arrangement, then you are moving the cursor across the left edge of one screen and the right edge of the other.

As I say, though, this is about the logical relationship between the two screens. It’s how the computer “thinks” about them. It does not necessarily about how the screens are actually physically arranged in your workspace. Thus it would be possible to arrange one screen physically above the other, as you see in the photograph at the beginning of this post, but choose a side-by-side arrangement as the logical relationship between them. If for some strange reason you’d decided to set things up this way, then you would move back and forth between upper and lower screens by moving the mouse right and left across the logical border between the two screens.

You might wonder just why anyone would do such a crazy thing. That is in fact what I with my G4 PowerBook and the external monitor. I must have had some reason for doing things that way, but I can’t recall it now.

Recap: Where Are We?

When my G3 tower machine died I decided to replace it with a G4 PowerBook. I also decided to keep the LCD monitor from the old G3 so I could run the G4 with two screens. Why’d I do this? Because I wanted a lot of display space so I could keep multiple windows open on multiple apps.

That’s all obvious enough, at least I think it is. But I’ve spent most of this post so far talking about how one assimilates this computer beast to one’s body. First I talked about learning to type, as keyboards are a ubiquitous way of interacting with computers. From there I said a bit about the mouse, which entered my repertoire with my first Mac. And then we had a longish digression on dealing with two screens, which turned out to be mostly about the mouse.

It’s worth thinking that through again. It’s all about space and how the body moves about the world through several sensory motor spaces. It’s one world, one 3D space (extended in time). But the visual system has its representation of that space; the musculo-skeletal system has its space; and our touch sensors have their space. We spend the first two or three years of our lives getting these spaces – and others (auditory, olfactory, taste) – synched up with one another so that our physical experience of the world is coherent.

When we learn to control a computer though a mouse and graphic user interface (GUI) we have to “break into” those sensory-motor arrangements in a basic, if in the end rather simple, way. It’s not particularly difficult to do, but it takes a bit of time and patience. And it’s easier to do it than to explain what’s going on, as I’ve been doing in a rather cursory fashion in this last batch of paragraphs.

The Trackpad and Beyond

And I haven’t even gotten to the trackpad, which, as I’m sure you know. Is another device for using your motor skills to move things around on the computer screen and thereby exert some control over the computer. Just in case you don’t have a trackpad in front of you that’s a trackpad in the bottom center of the photo, underneath Sparkychan’s right arm:

At first I was doubtful about the trackpad. Getting used to it was tricky and, like the mouse, took awhile. But in a few days I was fairly fluent with it and, over time, used it more and more in preference to the mouse, which I still kept. What was nice about the trackpad is that it was under my fingers along with the keyboard, so I didn’t have to move away from the keyboard to use it. But, when I wasn’t using the keyboard, when I was working with photographs, for example, I often preferred the mouse.

And I worked with photographs quite a bit. In the summer of 2004, before I’d switched to the G4, I bought a point-and-shoot camera so I could take photos of Chicago’s newly opened Millennium Park. I had no intention of doing much photography, but I got the camera out every now and then and walked the neighborhood pointing-and-shooting. Then, in 2006, I decided to photograph graffiti. That quickly became a major interest. I got a DSLR (digital single lens reflex) camera and starting taking lots of photos. Pretty soon I began straying away from graffiti and just took lots of photos.

As you may know, photo files are typically much larger than text files. Text files might be anywhere from 50K to 500K or 600K, but not much larger (unless they have embedded images). Photo files range from a megabyte to 10 or more megabytes (much more in in some cases). So I had to get an external hard drive to hold the photos and then another external hard drive to back everything up.

I don’t know how many photos I had when the G4 finally went bad. But it was lots. It didn’t go bad all of a sudden, it gave me warning signs for a year or more before I was finally unable to bring it back up. I’d delayed replacing it because Apple had made a major change in their hardware, shifting from CPU chips manufactured by Motorola to chips made by Intel. That meant, unfortunately, that when I moved from the G4 I’d probably have to replace most of my software, and that would be expensive. So I delayed things as much as I could and then, about three years ago, I had no choice but to get a new machine.

Fortunately, I could keep my Cinema monitor and my hard drives. While I wanted another laptop machine, they were too pricy. I opted for a Mac Mini, which is a small bare bones “pizza box” machine.

I was back to a single screen. Not good. And I didn’t have a trackpad, which wasn’t so annoying. On the other hand the newer processor allowed me to watch streaming video, which I really couldn’t do with the PowerBook, though I could manage YouTube Videos (I’d even made and uploaded a few). So I was introduced to the joys of binge watching, going through The West Wing, The Rockford Files, and half a dozen other shows at the rate of several hours a day. It was winter, a traditional downtime for me, and I watched a lot of old TV, and some movies too.

So, that was good. What was not so good is that, while the new machine was faster in some ways, it was also slow. My friend Greg tells me that the problem is that when the systems tech ported my old data and software to the new machine, he took it over in a block and so brought a lot of unnecessary junk with it. And that junk slowed things down. Perhaps. But it is also the case that the machine only had 2 gigs of RAM, which made things rather tight for my operating style, with half a dozen windows open at all times.

Whatever the case, using the machine was often very slow. And the hard drives were filling up with photos. And so, about two weeks ago, I decided to get a new machine. I opted for an early 2015 13 inch MacBook Pro with Retina screen, 256 megs of flash (solid state) storage, and 8 gigs of RAM. Rather than continue with the old Cinema screen, decided to replace it with a 23 inch NED monitor.

I’m back running with two screens – the Retina screen is a wonder of color and resolution. I’ve got a track pad, which I like. And I’ve got two thunderbolt external drives, one to hold my photos (80,000 of them) and the other for backups.

This machine will, of course, have to be replaced in a few years. Who knows what the technology will be like then. But I’ve got my eye on this beauty: