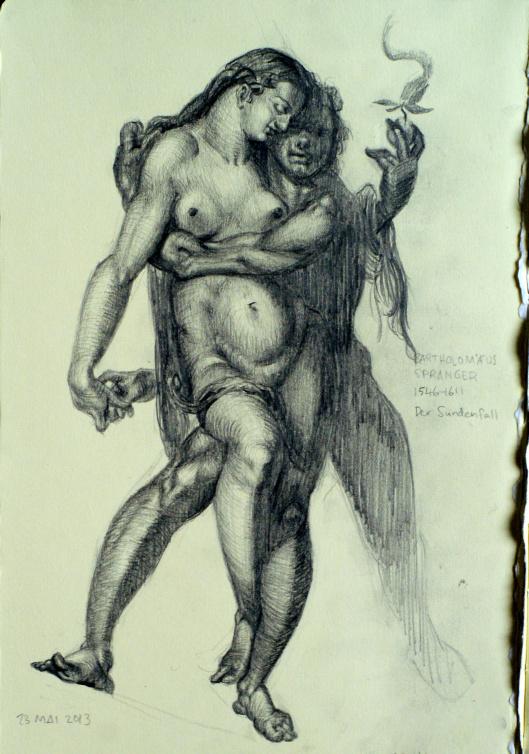

Copy after Bartholomäus Spranger, Der Sündenfall

It’s undeniable that the Dutch and Flemish painters particularly relished detail. When I look at their paintings I see the glee that sparkled in their eyes, thinking of the heavy texture of a rug and the crystal gleam of glass, the rumpled satin and copious strings of pearls—almost without a thought for their sitter. Every corner of the painting is precious space to be maxed out in all its textural glory. One squints in wonder at the precision with which paint is applied, with, one presumes, unimaginably tiny brushes. I’m a sucker for this. I don’t care if it’s showing off. I want to discover more and more.

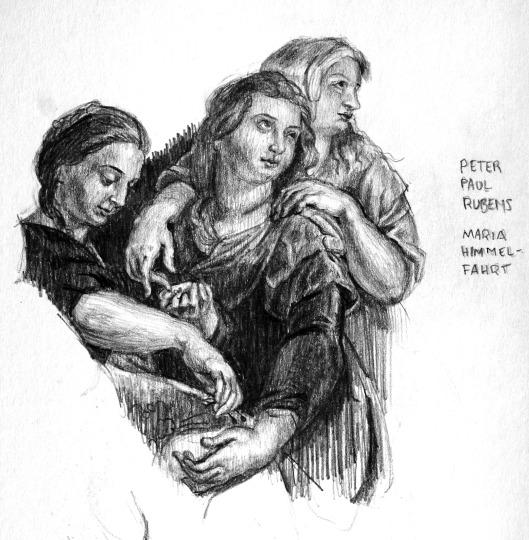

Holy fuck, detail of Peter Paul Rubens

There is a point, though, when detail becomes garish and visually distressing. It’s one thing to satisfyingly distinguish between course woven carpets and soft skin and silky garments, but another to be forced to train one’s eyes on pores and individual hairs and knuckle wrinkles. Hyperrealism is a visual torrent of truthful information that our eyes, when grappling with the real world, graciously blend into one viewpoint. We can’t concentrate on everything at once, and such paintings ask the impossible of us, forcing our eyes to train, hawklike, on every aspect at once. I’ve seen ceiling-high paintings that are like frightening projections of microscope slides of old people’s noses, and I have to say that I don’t think they are very clever. Has the artist a scientific interest in dermatology? Are they a failed biologist?

A broad simplification of this matter is summed up in the dichotomy of detail versus structure, which Nelson probes with some scepticism. Whence this dichotomy, he asks? Does it have its roots in ‘romantic versus classic? Instinct versus discipline? Liberal versus anal-retentive? Modernism versus tradition?’ (p. 145). I’m reminded of this Western inclination to equally partition things, divide them into ‘us and them,’ as Alice Jardine (in Walker 2009 p. 46) notes: ‘The question of “the couple” has become the object of contemporary philosophical fascination, where all metaphysical couples are in the process of being discoupled, recoupled differently and urgently: active/passive, form/matter, speech/writing, conscious/unconscious.’ Whether or not this coupling project is useful, it seems to hold our fascination, and has certainly been in my mind as I flit between the Dutch-German-Flemish and Italian-Spanish-French wings of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, unable to help engaging in comparative study.

Wöllflin (Nelson 2010 p. 145; 148) put forward this particular artistic and culturally ‘normatively informed’ coupling. According to his proposed division, Renaissance artists of the northern and more liberal regions are swamped in a glittering frenzy of detail, while their southern counterparts soberly attend to the structure of the entire image. Or perhaps the stiff and accurate detail is sober, and the giddy motion grows out of a compositional frenzy. In Nelson’s (p. 145-6) summarisation, ‘Whereas artists like Van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Robert Campin and Dürer fill their busy rectangles with copious detail in an even and democratic spread, artists like Giotto, Masaccio, Piero, Michaelangelo and Titian are interested in a single spatial proposition, with a key volumetric argument, usually centralised and tending to command a perspective of an ideal and single viewpoint.’

My own investigations have led me to believe it is not so simple as this. Certainly, I was amazed at the stiff simplicity of Titian’s (non-fur) drapery—the simple and ungraduated laying down of three tones in awkward triangular shapes. Where his faces were careful and smooth, his compositions focussed and kind to the viewer, his textures seemed sometimes a mere afterthought, an irrelevant feature that would only distract from his main pictorial assertion. And there is no denying the narrative motion inherent in a stunning painting by Strozzi, of the widow and her son with Elias, in which the textures are dampened and softened to great effect, letting the eyes marvel over the weight and presence of the subjects. And the Dutch brazenly flaunt the golden weave of baskets and the pink sheen of satin, and carefully delineate every leaf of a tree. Nevertheless, it seems more a question of degree and emphasis.

Detail of Bernardo Strozzi, The prophet Elias and the widow of Sarepta

Where Van Dyck paints incredibly subtle yet expressive faces and positively floating angel garments, the detail in which he revels is supported by a strong and intentional composition. I am in awe of his Vision of the blessed Hermann Joseph with Mary, the centre of which forms a diagonal rectangle between the faces, with a three-dimensional convergence of the arms of Mary, Joseph and the helpful angel. The fourth head to the left completes a satisfying arc through the four, closing off the design in a tight fashion. Detail does not interfere with or stand in isolation from the structure; the two function far more dependently.

Copy after Peter Paul Rubens, Maria Himmelfahrt

And when one considers the phenomenal Rubens, and his overwhelming visual cacophony of flying babies and intense if idealised character types, with their cascading hands, lavishly surrounded by exotic fruits, it seems that composition is equally in his mind, only with grander, more complex visions, interlocking countless tiny narratives. The voluminous flesh of his figures demonstrates more of a virtuosity with respect to the human form than a strict adherence to the truth of perception. His detail seems largely driven by questions of motion, unlike the more believable individuality of Van Dyck’s figures. A Rubens hand is above all engaged in some action, and mightily idealised; a Van Dyck hand belongs to its owner alone. As Nelson (p. 147) argues, the northern artists isolated by Wöllflin ‘nevertheless organised their fields fastidiously.’

Copy after Veronese, Lucretia

Veronese expertly directs the viewer through the narrative of the painting, but not at the expense of lavish decoration—heavy brocade, gleaming jewels, deftly-woven golden hair—his Judith and Lucretia are in fine murderess getup (homicide or suicide), and this brings a certain theatricality to the tight but expressive compositions. One’s eyes feast on the jewels at their shoulders, drawn to the most brightly-lit part, and unquestioningly follow their arms—symbols of action, I speculate—to the bloody acts at their fingertips, cloaked in darkness.

Detail of Veronese, Judith

Nelson wisely draws our attention back to the fact that the decisions we make as painters are based on perception, but ought not be enslaved by it. Every painter makes those decisions not only based on preference, cultural affiliations or schooled traditions, but in response to the stimulus itself. Perceptual art, he argues (p. 150), ‘is a poetic process of interpreting perception in order to make paintings and drawings. … The interest will always be in the strength of the image, the consistency of vision, the poetic agreements between the technique and the perception.’ Whichever camp sways you, your debt is to the subject alone.

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The visual language of painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.

Walker, Michelle Boulous. 2009. ‘Writing couples: Reading Deutscher on Sartre and Beauvoir.’ In Crossroads IV(1): pp. 45-52.