My humanist group hosted J. Anderson Thomson, a psychiatrist, speaking about his book, Why We Believe in God(s): A Concise Guide to the Science of Faith.

Everyone knows religion reflects trying to explain what we don’t understand; to gain a moral touchstone; to combat fears of death. All more or less conscious mental phenomena. But Thomson went deeper.

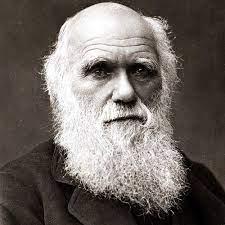

He began by twice quoting Jefferson in 1816, on how religious dogmas (as distinct from moral principles) have forever induced people to battle and torture each other over abstractions actually beyond the comprehension of any human mind. Charles Darwin was then nine, and would go on to supply the understanding of our origins equipping us to rise above Jefferson’s lament.

The evolutionary process he demystified reveals us to be, at the most fundamental level, “problem solving devices” aimed at gene replication. One’s own individual well-being and survival is just a means to that end.

This is Richard Dawkins’s “selfish gene” paradigm. Really ultimately just math — traits enhancing an organism’s likelihood of reproducing will proliferate in subsequent generations, carrying along the genes associated with them. In service to this our brains evolved — mostly performing functions not even in conscious awareness.

Thomson spoke of junk food and pornography as “super-normal stimuli” outclassing ones we encounter naturally, hijacking the brain to cause behaviors responsive to very deep-seated desires whose true evolutionary purpose is not to reward us but to get our genes into the next generation. Religion does similar.

It takes advantage of a key human evolutionary adaptation, “eusociality” — described by Thomson as “colony life” or an endless camping trip with close relatives. Religion meshes helpfully with this by enabling expansion beyond just family groups into larger (and thus stronger) social collectives.

He also stressed the salience of parent-child relationships, and how religion gains a foothold in our minds by mirroring that. Especially the mother-child bond. Belief in a deity mirrors knowledge of a mother’s existence, actually filling roles akin to a god’s. Mothers answer prayers; they’re seen as omniscient and omnipotent. A loving presence in challenging circumstances. They provide sustenance. Thomson placed the Christian communion sacrament in this context (though without specifically mentioning breast milk).

Another key theme is that religions ask us to suspend disbelief only within limited bounds — we’re set up with alarms against gross violations of the natural order, but religions tend to entail only modest tweaks to our understandings of how things work.

He also discussed ritual, especially “rhythmic physical activity” like dancing and even just touching. Affecting us on a deep subconscious level by boosting endorphin levels, thus raising pain thresholds and promoting interpersonal bonding. Mirror neurons come into play. Yet another deep mechanism religion exploits, with even nonbelievers finding it hard to resist an emotional response.

This put me in mind of my own experience. I was that rare child who never absorbed an iota of religious belief. I was also socially very laggard. Thomson’s presentation made me wonder whether those two things were connected. Seventy years later I still feel I lack some standard social genes; and my non-religiosity remains absolute.

Yet I’m not entirely without human social response. I’ve noticed a deep susceptibility to smiles. Seeing one provokes a warm feeling. Even if on the face of, like, a Putin, or a Trump! I find I must engage my rational brain to countermand that innate human response.

This is ultimately what Thomson was urging us all to do when it comes to religion.