Certain stories set an entire newsroom buzzing, and word of the death of Elvis Presley, 40 years ago today, spread like wildfire throughout the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. I had worked there for eight months, still getting used to the rhythms and quirks of the city’s lesser known newspaper. I stood far outside the inner circle of managing editors, city editors, feature editors and others who made decisions about what was and was not newsworthy. That, incidentally, would remain true for the entire five years I worked there.

Certain stories set an entire newsroom buzzing, and word of the death of Elvis Presley, 40 years ago today, spread like wildfire throughout the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. I had worked there for eight months, still getting used to the rhythms and quirks of the city’s lesser known newspaper. I stood far outside the inner circle of managing editors, city editors, feature editors and others who made decisions about what was and was not newsworthy. That, incidentally, would remain true for the entire five years I worked there.

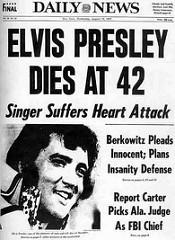

Curiosity grew quickly about the details surrounding Presley’s death, but that wasn’t what had everyone talking. Instead, rumors spread quickly that the G-D brain trust wanted to relegate the story inside, probably with the obits.

As a 6-year-old, I felt torn between my mom and dad. Mom, being a Southerner, wanted to watch Elvis’s 1956 appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. Dad found him crude, but he told me I could make up my own mind about whether to watch. The night of Elvis’s performance, I split the difference, standing in the doorway between the kitchen and the living room, fully committed to neither my dad, smoking in the kitchen, nor my mom, seated by the TV. I loved Elvis’s performance, though. Within a year, my dad had died of a heart attack. I was devastated, of course, but free of this little bit of tension between my parents.

Like most people my age, by the time Elvis died, I saw him more as kitsch than King. The jumpsuits, excessive weight, botched lyrics, and endless cover songs made him a caricature of his former self. I celebrated his comeback in 1968, but nine years later, the magic had disappeared.

Even so, I and my fellow reporters knew that keeping Elvis off the front page would be a mistake. He, Frank Sinatra and the Beatles changed the landscape of popular music in the 20th century. His legion of fans would never understand. In the end, the Globe-Democrat decision makers relented, and Elvis got his rightful place on Page One.

I’ve come to understand just how much a person’s judgment is shaped by when he or she comes of age. When Elvis died, he had been on the scene a bit more than 20 years, but he wasn’t part of the fabric of the lives of the Globe’s senior management, just as Taylor Swift is not part of the fabric of mine. I have no understanding of the passion her fans have for her, so I have a bit more insight into how the Globe editors underestimated the importance of Elvis’s death. Like me now, they were just doing the best they could.

A postscript: About a month later, Bing Crosby died. His front-page obituary was never in doubt.