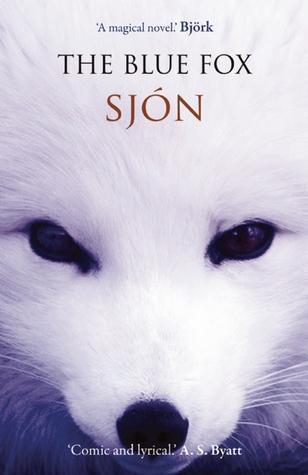

The Blue Fox, by Sjón and translated by Victoria Cribb

Most literature, for me, works as well as an ebook as it does as a paperback. Sometimes better, particularly if the book’s on the bulky side.

Not all literature though, and particularly I increasingly find not poetry. Poetry depends not just on words but also on placement on the page, on the sea of white around the little islands of black text. Layout, in poetry, is critical.

The Blue Fox isn’t poetry, but it’s close. In a fascinating interview with The White Review Sjón talks about how the book was structured almost as if it were music:

Sjón — I think the fact that I can take the form of the string quartet and use it as the basis of a novel is another proof of how dynamic the novel is. I’m sure that a composer writing a string quartet can learn something from a movie or the structure of film. It was music that gave me the idea of constantly breaking up the narrative. THE BLUE FOX would be a completely different novel if it were chronological. In it, there are constant cliff-hangers and repeated refrains – I’m playing with the element of two melodies that come together but never fully, only in the end finding a solution. It was very interesting that the first people who commented on the book were composers. They said it was very clear to them that I was always playing with volume of information versus text, which is the same thing they do – volume of tones versus time. You can take a melody and stretch it over five minutes, or compress it down to three seconds. They were very much aware of how I was playing with text versus information.

Information versus text. Text versus information. The Blue Fox is a tone poem in book form, a 112 page crystallisation of music on a page. I’m getting ahead of myself though, because I still haven’t said what it’s actually about.

The Blue Fox consists of two different, but connected, narrative strands. In the first a hunter pursues a blue fox, a rare and valuable prey. Their contest, his for a valuable pelt, hers for her life, takes on a mythic air as Sjón fills each page with just a few lines of text letting space and silence surround the sparse words.

Here’s how it opens:

Blue foxes are so curiously like stones that it is a matter for wonder. When they lie beside them in winter there is no hope of telling them apart from the rocks themselves; indeed, they’re far trickier than white foxes, which always cast a shadow or look yellow against the snow.

A blue vixen lies tight against her stone, letting the snow drift over her on the windward side. She turns her rump to the weather, curls up and pokes her snout under her thigh, lowering her eyelids till there’s the merest hint of a pupil. And so she keeps an eye on the man who has not shifted since he took cover under an overhanging drift, here on the upper slopes of Asheimar, some eighteen hours ago. The snow has drifted and fallen over him until he resembles nothing so much as a hump of ruined wall.

The creature must take care not to forget that the man is a hunter.

Each section of the book comes with dates attached, the first being three days from 9 to 11 January 1883. It’s rooted therefore in the actual: an actual hunter; an actual fox; a particular place and day with particular weather. It couldn’t be more specific.

At the same time though, the sense is of a more timeless encounter. Man and fox both seem archetypal: at this point he is simply “the man”; she “the vixen”. They appear to have emerged from a folktale or saga.

His guts rumbled and the man discovered that he was hungry; he hadn’t tasted a bite since gorging himself on boiled fish before he set off, but that was more than twenty hours ago.

He had eaten a bit of ice since then, truth be told, but that was dull and insubstantial fare. He opened the bag:

Hand-thick slabs of lamb, rye cakes with sheep’s butter, sour as gall, topped with mutton sausage, a dried cod’s head, pickled blood-pudding, dried fish, curd porridge and a lump of brown sugar.

Yes, all this was in his mess-bag.

As you read there’s a sense of themes emerging not in the familiar literary sense, but in a musical one. Phrases recur, such as the title of this review, and that entire first quoted passage above is used twice, verbatim. It’s prose as melody, repeated refrains.

The second narrative strand features a biologist, Fridrik Fridjonsson, who has to bury a young woman named Abba that he took in some years before as his maid. Abba was destitute when he first met her, an outcast from the local community. Fridrik had only briefly returned to Iceland to settle some family affairs, but recognised that Abba had Down’s Syndrome and from compassion decided to stay and to protect her. The parish then was served by a Reverend Jakob:

This incompetent minister was so used to his parishioners’ boorishness – scuffles, belches, farts and heckling – that he affected not to hear when Abba chimed in with his altar service, which she did both loud and clear and never in tune. He was more worried that the precentor would drown in his neighbours’ spittle. This fellow, a farmer by the name of Gilli Sigurgillason from Barnahamrar, possessed a powerful voice and sang in fits and starts, gaping so wide at the high notes that you could see right down his gullet, and the congregation used to amuse themselves by lobbing wet plugs of tobacco into his mouth – many of them had become quite good shots.

Four years later Reverend Jakob died, greatly regretted by his flock; he was remembered as ugly and tedious, but good with children.

His successor was Reverend Baldur Skuggason, who introduced a new era in church manners to the Dale. Men sat quietly on the benches, holding their tongues while the parson preached the sermon, having learnt how he dealt with rowdies: he summoned them to meet him after the service, took them round the back of the church and beat the living daylights out of them. The women, meanwhile, turned holy from the first day and behaved as if they had never taken part in teasing ‘the reverend with the pupil’. They said it served the louts to whom they were married or betrothed right, they should have been thrashed long ago; for the new parson was a childless widower.

Reverend Skuggason swiftly banned Abba from the church, seeing no place there for what he termed “‘the ravings of an idiot'”. Although Abba “knew no greater happiness than to dress up in her Sunday best and attend church with other people”, Reverend Skuggason would not tolerate her and none of his flock cared enough to speak on her behalf.

Reverend Skuggason is the hunter, bringing the two strands together in one man. He denies Abba; he pursues the fox; he is a priest but he knows no pity.

The Blue Fox builds its mood slowly, and its few revelations come all the more powerfully for that. Sjón brings the harsh landscape and the harsh people it breeds both to freezing life. It’s notable that the only one of them to show any mercy is Fredrik, who left for Copenhagen and never meant to return.

Two narrative strands then, and two tonal strands too. The utter factuality of dates, lists of packed provisions, medical diagnoses; but simultaneously a changeling woman come in from the woods and befriended by a traveller, a huntsman and a fox of unsurpassed rarity, beauty, cruelty, hypocrisy, innocence, kindness. History and fairy tale, intertwined and inseparable.

Other reviews

The Blue Fox has been generally pretty well received (though many reviews contain some fairly hefty spoilers so it’s worth being a bit careful which you read, you should particularly avoid the one in the Independent which in a fairly short piece still somehow manages to give away every story development in the book). Two reviews I was particularly impressed by are Scott Pack’s here at his Me and My Big Mouth blog, and Sarah Hesketh’s here for ReadySteadyBook.

I’d also recommend this interview with Sjón by Stu at his Winstonsdad’s blog. Sjón explains among other things that The Blue Fox is in part inspired by Schubert’s string quartets, and describes the music that inspired his other books.

Filed under: Icelandic Literature, Novellas, Sjón Tagged: Sjón, The Blue Fox