By Janice Maskort and Val Hewson

‘John who?’ we said at Reading 1900-1950, where we think we know our popular 20th century writers.

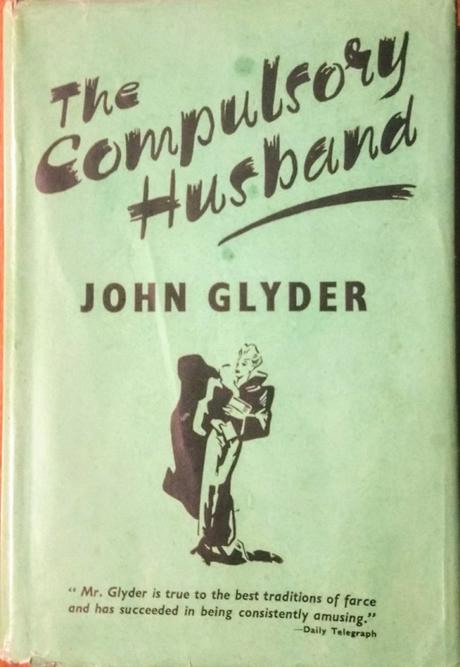

John Glyder came to notice via Mary who features in our sister project, Reading Sheffield. Mary, whose interview is here, kept a record of what she read between the ages of 15 and 17 (1936-38). More or less at random, Janice chose The Compulsory Husband, one of two books by John Glyder on Mary’s list. Realising that he was now unknown, Janice and Val teamed up to investigate.

Janice: I was well warned, when The Compulsory Husband arrived in the post. It was published by Herbert Jenkins Ltd, which specialised in light and humorous fiction. P G Wodehouse was their star author. On the dustjacket there is a review:

Mr Glyder is true to the best traditions of farce and has succeeded in being consistently amusing. (Daily Telegraph)

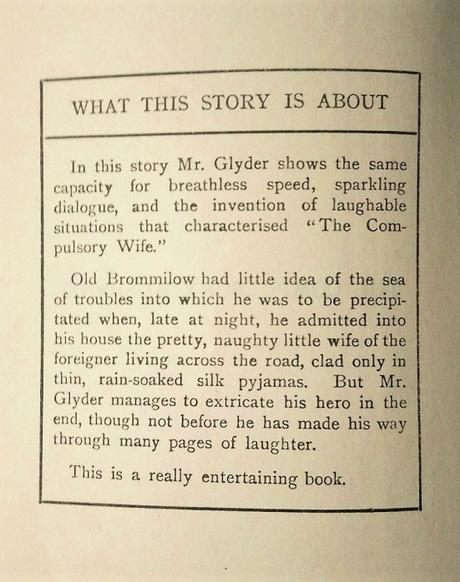

Opposite the title page it says:

In this story Mr Glyder shows the same capacity for breathless speed, sparkling dialogue, and the invention of laughable situations that characterised The Compulsory Wife. … This is a really entertaining book.

At the end there is a list of ‘John Glyder’s Books of Laughter’.

The plot is impossible but here is a taster. Mr Brommilow, ‘well-covered and placid in aspect’, stays at home, when his wife goes off to visit her sister. Late at night, the ‘pretty, naughty little wife of the foreigner living across the road’ turns up, ‘wearing only thin, rain-soaked silk pyjamas’. Naturally, Brommilow invites her in. Hilarity, as they say, ensues. His mother-in-law turns up. There is a flood from the bathroom where he has told the girl to take a bath.

As he flung open the bath room door, he was met by a cloud of steam. He heard water pattering gently over the edge of the bath. There was water all over the floor. That ought never to have happened in a properly conducted bath. There ought to have been a safety valve or an overflow place or something. He felt his way through the opaque white mist to the taps and turned them on farther in his excitement.

Then the girl’s husband throws her out, dumping her clothes and furniture in Brommilow’s garden. And… But it is too exhausting to go on. And it doesn’t really matter anyway.

All in all, John Glyder seems made for Reading 1900-1950. Why was he popular in his day but now forgotten?

Val: He was certainly frequently reviewed. There are perhaps 200 short reviews in British provincial newspapers between the 1920s and ‘40s.

In this riotously funny story of a compromising contretemps John Glyder has placed himself in the forefront of humorous writers. … (Western Mail, 1 March 1928, on The Compulsory Wife)

The Compulsory Husband, a really funny yarn, full of the sparkling dialog that made the companion novel so readable. (Aberdeen Press and Journal, 4 October 1928)

Mr Glyder has talent for evolving amusing situations, and his dialog is eminently suited to the style of his story. This is an excellent book for an idle hour. (Sheffield Independent, 12 November 1928, on The Compulsory Husband)

Those who laughed heartily over The Compulsory Wife will feel that John Glyder has not failed them in the bright dialogue, bizarre situations, and rapid movement of his latest novel. (Dundee Courier, 16 November 1928, on The Compulsory Husband)

The Compulsory Honeymoon of John Glyder’s rakish invention is, in popular parlance, a ‘wow,’ a hilarious, non-stop comedy of cross-purposes, back-chat, seaside bungalows, timid and obstreperous females. (Aberdeen Press and Journal, 28 March 1929)

With a fuller, richer humor than P. G. Wodehouse ever knew, John Glyder scores another success with Lady in the Moon. … It is supreme foolery. (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 12 December 1942)

Full of laughter and chuckles … The Compulsory Honeymoon completes a trilogy of wonderfully laughable stories which should establish John Glyder as one of the best humorists of to-day. It is a mirth-provoking novel to which Messrs Tom Walls and Ralph Lynn – the mirth-provokers of the stage – should be introduced. (Dundee Courier, 4 April 1929)

Janice: In contrast to all those contemporary reviews, I struggle to believe that people bought his books. I find The Compulsory Husband excruciating. A contrived and obvious plot. Caricatures, not characters. Leaden dialog. No wit. This novel is both ludicrous and pedestrian.

Mr Brommilow … tripped against the hat-box and kicked it savagely down the passage. The lid came off. Hats emerged, absurd hats, like cocoons, dozens of them. Mr Brommilow kicked them here, and kicked them there, booted the remnants of the box again, called upstairs and became conscious that Mrs Pilluski was already out on the landing, clad in his wife’s pyjamas, and busily rubbing her curly locks with a towel.

‘Why,’ she inquired gravely, are you kicking those things about, Nunkie?’

‘Because,’ said Mr Brommilow, ‘I feel like it.’

‘Naughty man,’ she said and, sitting on the bannister rail, descended rapidly and gracefully.

‘I believe you’ve been listening,’ he said.

‘I have,’ she confessed unblushingly. ‘I got tired of sitting in the bath room. Who is that woman?’

‘That woman,’ said Mr Brommilow, ‘is my mother-in-law. Her name is Mrs Chatterton.’

‘I don’t think she likes me. I wonder why? I haven’t done anything to her. …’

Val: The British Library lists 24 novels published by Herbert Jenkins between 1928 and 1951. The titles (and the dust-jacket illustrations) suggest a formula: Woman Friday (1932), Eva and Adam (1933), Flaming June (1949), Jill-in-the-Box (1932), She Stayed the Night (1936), Rude Awakening (1948?), Half-Hose (1935) and Beast and Beauty (1934).

Two of them, The Compulsory Husband and The Compulsory Wife, were made into British films in 1930 and 1937 respectively. Another sign of popularity perhaps.

Janice: So who was this popular author? We can’t be quite sure without more research than we have the resources for, but John Glyder seems a nom de plume for Allen George Roper. According to a bibliography by Allan J Hubin, he was born around 1887 in Croydon, wrote crime fiction, and was a prep school teacher and a eugenist. The interest in eugenics was probably limited to an essay, Ancient Eugenics, which apparently won him Oxford’s Matthew Arnold Memorial Prize in 1913. After graduating, he became a schoolteacher in Knaresborough, Yorkshire, and wrote Album Latinum, a basic Latin vocabulary published by Blackwells in 1919.

Val: Crime fiction? All the titles we found sound like farce. However, he contributed to The Strand, which famously published the Sherlock Holmes stories, and other magazines:

- Ballantyne Balances It Up (The Strand Magazine, July 1929)

- The Wager (The Strand Magazine, October 1931)

- The Register (The Strand Magazine, February 1932)

- Change for a Shilling (The Strand, January 1934)

- Last on the List (The 20-Story Magazine, Dec 1932)

- Speaking Likeness (The 20-Story Magazine, April 1933)

Perhaps this is where the crime comes in.

Janice: To me the novels are crimes. But to go on…

Glyder published nothing after 1950, according to the British Library catalogue, and died in 1957, but there seems to be no obituary in either name. Did he keep his two careers as schoolteacher and ‘farceur novelist’ strictly separate? Is that why his death passed unnoticed?

Val: You think that the school governors and parents might have disapproved if they had known that the man who taught their sons Latin, wrote books like Beast and Beauty? Or he might have written to supplement his school salary, or because he enjoyed it. You may not like them, but the man who wrote those novels surely had a sense of fun:

‘Quite,’ agreed Mr Brommilow. … It’s all very difficult. You see, my wife’s had an accident.’

‘’Scuse me,’ said Bill. ‘’Ow many wives ‘ave you got?’

‘Oh – er – one, of course,’ said Mr Brommilow.

‘But I thought this ‘ere was your wife?’

‘No,’ said Mr Brommilow. ‘Not exactly. You see, she’s is – er – really someone else’s wife. Only – er –‘

‘’You kind of borrowed ‘er, same as you borrowed the car? …’

Janice: I suppose so. But that’s it. Surely farce works best on screen or stage. (It’s interesting that the Dundee Courier quoted above commends John Glyder to Tom Walls and Ralph Lynn, stars of the Aldwych farces.)

Val: Several of his reviewers compared him, favourably, with P G Wodehouse.

PG Wodehouse had better look to his laurels, for John Glyder, already his equal in the concoction of hilarious farce, is promising to rival him in the matter of output. (Western Morning News, 28 March 1938, on Any Port)

Janice: To my mind the comparisons are lazy journalism, and the similarities superficial. Yes, they both deal in the absurd, but John Glyder is cruder, and his use of language considerably poorer. His tropes – the scantily-clad beauty, the formidable mother-in-law, the bemused innocent with no control over events – are tired – were tired even then. He was, as his reviews suggest, an undemanding weekend or wet afternoon read, but nothing more… That’s really why he has been forgotten.

Val: Not someone you’re keeping on your shelves then?

Janice: Well, no.