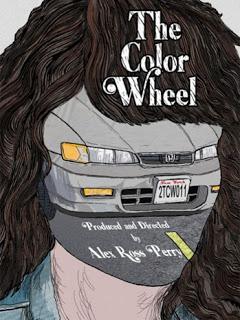

It is both immediately apparent and hard to believe that Alex Ross Perry’s second feature, The Color Wheel, is entirely scripted as the director claims. The flesh-peeling barbs that Ross Perry and co-writer Caren Altman lob at each other as warring siblings Colin and J.R., respectively, are so deft and precision-targeted that the broader strokes of improv responses seem inadequate for producing them, yet the speed and rhythm with which they deflect and parry feels so spontaneous, not at all memorized and practiced. The dialog is as separated from the prevailing status quo of American comedy as it separates the characters from each other, from the sardonically drawled “Nice shirt” that opens the film to a multi-front war the siblings open between themselves and everyone around them.

It is both immediately apparent and hard to believe that Alex Ross Perry’s second feature, The Color Wheel, is entirely scripted as the director claims. The flesh-peeling barbs that Ross Perry and co-writer Caren Altman lob at each other as warring siblings Colin and J.R., respectively, are so deft and precision-targeted that the broader strokes of improv responses seem inadequate for producing them, yet the speed and rhythm with which they deflect and parry feels so spontaneous, not at all memorized and practiced. The dialog is as separated from the prevailing status quo of American comedy as it separates the characters from each other, from the sardonically drawled “Nice shirt” that opens the film to a multi-front war the siblings open between themselves and everyone around them.Likewise, Ross Perry’s direction serves to radically break the film from modern trends of American independent filmmaking. Instead of being shot on affordable, slick, color DV, Ross Perry and cinematographer Sean Price Williams use black-and-white, gloriously grainy 16mm film stock. The choice of filming material is the film’s first and best-sustained joke, its anachronism an ironic reminder that its format used to be the preferred method of filming “realism” but now looks like artistic license. What was shorthand for real now looks decidedly the opposite when stacked against HD video, and it makes one wonder when that, too, shall be seen as almost classical. And though the film concerns two twentysomethings in the grip of anomie and stagnation, the 16mm removes The Color Wheel from even the most stretched definition of “mumblecore,” a nebulous term carelessly used by all (including this writer). Nothing about this is Sundance fare, but that only further defines it as a true independent work of art.

Compared to the shallow focus blurs that have announced protagonists’ insularity for the last few years, Ross Perry and Williams favor deep focus shots of alternating distances. The characters of this film are certainly solipsistic, but Ross Perry ably communicates that through starker, more distanced shots, using the sense of space rather than suffocating proximity to capture his characters’ loneliness. The camera also adds a visual element to some punchlines, such as when J.R. makes dark jokes about her brother being molested and Ross Perry cuts to a brief insert shot (possibly in J.R.’s POV) of a close-up on Colin’s crotch. In another instance, Ross Perry revitalizes the tired smash-cut punchline of someone insisting he or she will not do something and then suddenly there they are, doing that very thing. Ross Perry himself starts the complaint when J.R. insists Colin buy some new clothes, but the director had himself cut off in the editing bay, placing the abrupt cut not at the end of his refusal but before it even finishes. Shot patterns tend to move from farther away to close as a scene wears on, the squabbles between J.R. and Colin and the pair of them against others segmenting people from each other via the confines of the frame.

This movement of big to small is reversed by the dialogue, which starts with astonishing bluntness and gradually spirals out into more abstract jabs. Conversations between the siblings play as if rewinded, the passive-aggressiveness typically saved for deeper into the chat as the more withering remarks are dispensed with first. It is as if they acknowledge the easiness of a frontal assault and thus make it the first level of their game and save the more complex, oblique snips for the challenge of sustaining a battle. The pair’s interactions with other people, though, are less linear. Around others, they turn their singles game into a kind of doubles, and the rules shift to reward the sibling for getting the closest to directly attacking someone else without getting caught.

This can be seen most playfully near the start of the film, when the brother and sister stop at a motel on their way to J.R.’s ex-boyfriend to collect her belongings. The motel is run by an arch-conservative loon so committed to only allowing married couples to share the same room that he will not even allow siblings to share one. Thus, he prompts a quick battery of sarcasm from Colin and J.R. as they pretend to be husband and wife and see just how obvious they can make their scorn without being noticed. (Even so, the manager gets his revenge in a portent of plot developments to come.) The other third parties with whom they come into contact, however, bring their own ammunition. J.R.’s ex, her former professor, greets J.R. with his new student squeeze hanging on his arm and proceeds to taunt her as viciously as Colin. Likewise, a later party that sees Colin and J.R. tricking each other (and themselves) into attending a party with old high school friends where everyone gets in on the one-upmanship as everyone lies about their status in life and sets about forcing another to tell the truth. Whomever breaks first, loses.

Ross Perry introduces Colin and J.R. as such loathsome creatures that it can be a shock to be confronted by the outside elements, who are even worse. Instead of wallowing in his protagonists’ mutual loathing, he gradually, subtly brings them together, even bringing a certain level of empathy to these hyperbolically alienating people. J.R. needs to be told to grow up, but when such lines come out of the mouth of a professor who blithely sleeps with his students and talks as childishly and venomously as the leads, the lines refract back onto his own personality. Similarly, the party sequence masterfully dismantles the urge to gloat over old classmates, as any attempt to display intellectual and material superiority will only paradoxically revert the contenders back to high school, where they were all equally unimportant. In both cases, J.R. is reduced even further to childishness as her vain attempts to verbally destroy her targets push her closer to desperation.

Perhaps that is why J.R. and Colin slowly grow closer: they snipe at each other as hard as they do for anyone else, but neither has any sliver of superiority that makes their lonely anger useless in toppling a foe. Ross Perry regularly lays tracks toward the film’s climax from the start, undercutting the shock of its twist but better staging it as the final punchline, albeit one as unexpectedly sweet as it is transgressive. The Color Wheel emerges, wildy, brazenly and unorthodoxically, as a perverse fable, a mad visualization of the line that exasperated parents try to tell their bickering tots, “You’ll be there for each other when no one else will.” In a film that shows off such incredible camerawork and such dark but uproarious dialogue, the carefully set up moral plotting is almost icing on a cake, albeit one that confirms this film, and its maker, as one of the most exciting things to hit American indie filmmaking in some time.