Extreme weather is by definition rare on our planet. Violent storms, scorching heat waves and biting cold spells illustrate what the climate is capable of at its worst. But as the Earth's climate warms rapidly, largely due to the burning of fossil fuels, the range of possible weather events, including extremes, is changing.

Scientists define "climate" as the distribution of possible weather events observed over a period of time, such as temperature ranges, rainfall totals, or hours of sunshine. From these, they construct statistical measures, such as average (or normal) temperature. Weather varies on different time scales-from seconds to decades-so the longer the time period over which climate is analyzed, the more accurately these analyses capture the infinite range of possible configurations of the atmosphere.

Typically, meteorologists and climate scientists use a 30-year period to represent climate, updated every decade. The most recent climate period is 1991-2020. The difference between each successive 30-year climate period serves as a very literal record of climate change.

This way of thinking about climate falls short when the climate itself is changing rapidly. Average global temperatures have risen by about 0.2°C per decade over the past 30 years, meaning that the global climate of 1991 was about 0.6°C cooler than it is in 2020 (after accounting for other annual fluctuations), and even more so than now.

A moving target for climate modelers

If climate is a range of possible weather events, then this rapid change has two implications. First, it means that part of the distribution of weather events that encompasses a 30-year climate period occurred in a very different background climate: for example, northerly winds in the 1990s were much colder than those in the 2020s in northwestern Europe, thanks to Arctic warming that was almost four times faster than the global average. Statistics from three decades ago no longer represent what is possible today.

Second, the rapidly changing climate means that we have not necessarily experienced the extremes that modern atmospheric and oceanic heat can produce. In a stable climate, scientists would have several decades to get the atmosphere into its various configurations and produce extreme events, such as heat waves, floods, or droughts. We could then use these observations to build an understanding of what the climate is capable of. But in our rapidly changing climate, we effectively only have a few years - not enough to experience everything the climate has to offer.

Extreme weather requires what meteorologists would call a "perfect storm." For example, extreme heat in the United Kingdom typically requires the northward movement of an air mass from Africa, combined with clear skies, dry ground, and a stable atmosphere to prevent the formation of thunderstorms that release the heat.

Such "perfect" conditions are inherently unlikely, and years can go by without them occurring - while the climate continues to change in the background. Based on an understanding of observations alone, this can leave us hopelessly unprepared for what the climate can do now, if the right weather conditions all come together.

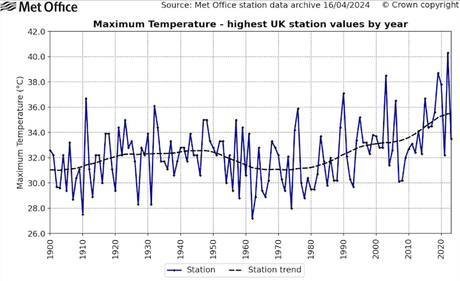

Surprising recent examples include the extreme heatwave in the Pacific Northwest of North America in 2021, which saw temperatures exceed the previous Canadian record maximum by 4.6°C. Another example is the occurrence of 40°C in the UK in the summer of 2022, which exceeded the previous UK record maximum set just three years earlier by 1.6°C. This is partly why the true impact of a fixed amount of global warming takes decades to see, but of course we can no longer use this method - as the climate is changing rapidly.

Playing with fire

To better understand these extremes, scientists can use ensembles: many runs of the same weather or climate model that are each slightly different to show a range of plausible outcomes. Ensembles are routinely used in weather forecasting, but can also be used to assess extreme events that could happen even if they are not actually happening at the time.

When 40°C first appeared in ensemble forecasts for the UK ahead of the July 2022 heatwave, it revealed the kind of extreme weather that is possible in the current climate. Even if it had not come to fruition, its mere appearance in the models showed that the previously unthinkable was now possible. In fact, several naturally occurring atmospheric factors combined with background climate warming to deliver the record-breaking heat on 19 July that year.

The highest temperature recorded in the UK each year from 1900 to 2023

Later in the summer of 2022, after the first 40°C, some ensemble weather forecasts for the UK showed a situation where 40°C could be reached on several consecutive days. This would have posed an unprecedented threat to public health and infrastructure in the UK. Unlike the previous month, this did not happen and was quickly forgotten - but then again it shouldn't have been.

It is not certain that these model simulations accurately represent the processes involved in producing extreme heat, but we should still heed the warning signs.

Despite a record-warm planet, the UK's summer of 2024 has been relatively cool so far. Global temperatures over the past two years have been far above anything previously recorded, and so potential extremes are likely to be even further removed from what we've experienced so far.

Just like in August 2022, we'll get away with it this time, but next time we might not be so lucky.

Don't have time to read as much about climate change as you'd like?

Instead, get our award-winning weekly digest in your inbox. Every Wednesday, The Conversation's environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that digs a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 35,000+ readers who have subscribed so far.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Simon H. Lee has received funding from NERC and the NSF. Hayley J. Fowler has received funding from NERC and the European Research Council. Paul Davies is president of the World Meteorological Organization.