This blog post is part of a monthly Eye Level feature on our exhibition The Civil War and American Art. Curator Eleanor Harvey talks about many of the important intersections between American art and the Civil War. The exhibition runs through April 28, 2013.

Frederic Edwin Church, Cotopaxi, 1862, oil on canvas, Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Robert H. Tannahill Foundation Fund, Gibbs-Williams Fund, Dexter M. Ferry Jr. Fund, Merrill Fund, Beatrice W. Rogers Fund, and Richard A. Manoogian Fund. The Bridgeman Art Library

American landscape painters rarely depicted Civil War battlefields, yet they often used weather and terrain to convey the war's emotional tenor. By 1862 the nation was locked in a bloody Civil War with no end in sight. Journalists, preachers, poets, and soldiers wrote about extreme weather and violent natural events to describe a world that was coming apart at the seams. Volcanoes had become a popular metaphor to symbolize the war's destructive force. During 1862 Frederic Church worked on his monumental image of Cotopaxi. In this painting the cinder cone of the erupting volcano dominates a panoramic sweep of the Andean plateau. The smoke and ash rolling from the caldera drift down the side of the mountain, nearly obliterating the surrounding landscape.

Although Cotopaxi is not a painting specifically about the Civil War, it is a landscape suffused with it. The critics of the day recognized the signs. In the American press, volcanoes were variously described in terms of bombs or heavy artillery, the ash clouds reminiscent of cannon smoke drifting across the battlefield. In a review of Church's painting the New York Tribune described volcanoes as "pillars of warning rather than of guidance." A reviewer writing for the Albion described the ash-laden sky as "the war-clouds, rolling dun" that eclipsed the light. The line comes from a poem written in 1803 by Scottish poet Thomas Campbell called "Hohenlinden," about a bloody battle fought near Munich in 1800 during the French Revolutionary wars. Campbell's volcanic imagery mirrors that of Church's canvas, the super-heated palette of reds and oranges conflating sunlit water with molten lava, and rivers with blood. Like the impenetrable, sulfurous smoke from the cannons that often rendered opponents unable to see each other, Church's ash cloud descending the Andean slopes threatens to blot out the sun.

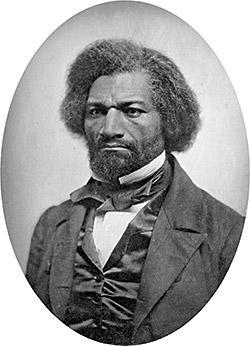

Frederick Douglass, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

During the Civil War, volcanoes were widely invoked as harbingers of societal upheavals. Frederick Douglass (1818—1895) (image) delivered an address in June 1861 titled "The American Apocalypse." He affirmed, "Slavery is felt to be a moral volcano, a burning lake, a hell on the earth, the smoke and stench of whose torments ascend upward forever." Race slavery was North America's volcano, a simmering force waiting to erupt explosively. It was a potent image that was often repeated in sermons and in the press across the North. A little over a year later, as Church completed Cotopaxi, the "moral volcano" of slavery became the central, burning issue of the war itself with Lincoln's announcement of the provisional Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. Accordingly, all slaves in the Confederacy were legally free as of January 1, 1863. By that time the American Eden had already been destroyed by Civil War, setting the stage for a political and spiritual transformation that could reshape the nation, much as Church's volcano would reshape the landscape.

Posted by Jeff on December 4, 2012 in American Art Here

Comments

I thought I recognized this painting from my years researching the New York Public Library's collection and its "deaccession" history. You might expand the story by including the work's provenance, as cited in the DIA website: "James Lenox (It was commissioned by him), New York, 1862-80. Lenox Library (later New York Public Library), New York, 1880-1945. M. Knoedler and Co., New York, 1945 John Astor, Miami, Florida (He was a descendent of Lenox), New York, 1945-76. Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York, 1976. DIA in 1976."

Did James Lenox imbue the subject with the same meaning as you do? Did he commission the work in 1862 especially for that reason? I don't know his biography well enough to comment, but it seems a possibly fruitful line of inquiry. Also given that the Smithsonian American Art Museum's own Cotopaxi by Church (1855) is relatively peaceful.