Prominent politician Adrien Marquet was mayor of Bordeaux from 1925 to 1944. In many ways he transformed the face of the city but has mainly gone down in history as the man who was at the helm of Bordeaux throughout the dark years of the Second World War. Therefore, despite highly-visible physical traces of Marquet’s legacy throughout the city, no streets, squares, buildings or bridges bear his name. So what did Marquet achieve and why has he been air-brushed out of the city’s history?

Adrien Marquet was born on October 6th 1884 in the house that was his family home, at 104 Cours Victor Hugo. After a relatively uneventful middle-class childhood, he qualified as a dental surgeon aged 19, although that year’s turning point was in fact his decision to sign up as a member of France’s Socialist Party. He became an active supporter of the movement, was appointed secretary of the Gironde branch of the SFIO (Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière) and was elected city councillor in 1912, although the outbreak of war and the Socialists’ subsequent struggles put his gradual political ascension on hold. However, in 1924, now aged 40, Marquet gained a seat as député within the National Assembly, and this paved the way to him being elected mayor of Bordeaux the following year.

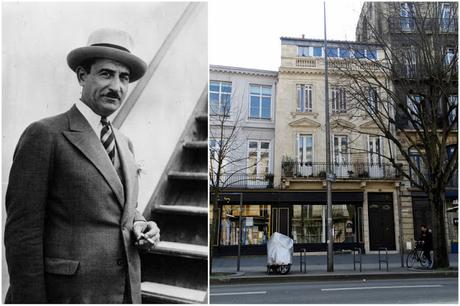

Adrien Marquet and, a-hem, his trademark toothbrush moustache in 1932 (photo source: Wikipedia), and his childhood home on Cours Victor-Hugo.

As the Great Depression took hold, Marquet took a proactive stance to enable Bordeaux to cushion the impact of the recession, stimulate the economy, create housing, schools, jobs and lay the foundations for durable development. This most notably resulted in the 1930 launch of the ambitious “Plan Marquet” programme, to structure the development of a whole host of buildings and facilities throughout the city, many of which shared an elegant art deco style which was very much of its time, as overseen by chief city architect Jacques d'Welles.The most notable examples of these endeavours include the Stade Municipal (familiar to us now as Stade Chaban-Delmas, also formerly known as Parc Lescure but renamed in honor of Marquet’s successor!), Piscine Judaïque swimming pool, the Bourse du Travail labor exchange, and more functional buildings such as the recently-demolished abattoirs, the head office of the local gas distribution board (now the trendy Mama Shelter hotel) and former Invisible Bordeaux subject the Saint-Jean postal sorting office. Not all the projects were on such a large scale: take, for instance, the public baths and showering facilities built in the right-bank Bastide quarter, as also featured on the blog some time ago. And while Stade Chaban-Delmas is particularly well-known, Marquet also initiated the construction of a smaller sports stadium in the Bastide neighbourhood; it was even known for some time as Stade Adrien-Marquet before becoming better-known as Stade Galin!

Marquet's physical legacy: the Stade Municipal (now Stade Chaban-Delmas, 1938), Piscine Judaïque (1935), Bourse du Travail (1938) and Siège de la Régie du gaz et de l'électricité (circa 1936)... now a Mama Shelter hotel!

The Bastide quarter public baths and showers (circa 1930, now a pocket theatre), Saint-Jean postal sorting office (1929, now office space with a ground-storey car park) and Stade Galin (1936, initially known as Stade Adrien-Marquet), complete with freshly-laid artificial turf.

There were to be a number of twists and turns in Marquet’s political path. At the 1933 national congress of the SFIO, Marquet’s statements on the subject of “order, authority and the nation” (at the time he was developing an interest in the forms of authoritarianism taking hold in Germany and Italy) were rejected by party director Léon Blum (who claimed he was appalled: “je suis épouvanté”). Marquet, along with a number of other MPs, was dismissed from the party; they went on to form their own movement, PSDF (Parti socialiste de France), although the arrangement would be short-lived as Marquet was soon dismissed from that party too.In early 1934, the French government was in turmoil in the slipstream of antiparliamentary demonstrations held in Paris, and Marquet was appointed Labour minister under the head of government, Gaston Doumergue. A nationwide take on the Plan Marquet was conceived and rolled out before faltering when the government collapsed before the end of that year. Marquet went on to found his own political movement, le Parti néo-socialiste, and was re-elected as an MP the following year. All of which brings us up to 1940 and Marquet’s appointment as Interior Minister in the first government led by Maréchal Pétain, although Pétain would soon relinquish him of this position: two months later Marquet was replaced by Marcel Peyrouton. Despite occasional attempts to break back into national politics Adrien Marquet was able to switch his focus back to Bordeaux, his wartime philosophy being summed up by a statement he had made during a radio broadcast: “We must reconcile the German and French viewpoints. Life getting back to normal depends on this collaboration.” (“Il faut concilier les points de vue allemande et français ; de cette collaboration dépend le retour à la vie normale.”)

The self-preserving collaboration-based approach - which was also tangible in the weekly newspaper he founded, Le Progrès - paid dividends throughout the War, but when Bordeaux was liberated, Marquet was bound to instantly pay the price, despite his claims that his negotiating skills had contributed to the Germans leaving quietly rather than leaving a trail of destruction throughout the city. On August 29th 1944, Marquet was arrested ahead of being imprisoned at the Fort du Hâ in the city center. He was put on trial in late 1947 and was acquitted on January 29th 1948, having served 40 months in jail, although he was condemned to ten years of “national indignity”, automatically forfeiting his civil rights.

Marquet was however itching to return to politics, and repeatedly filed requests for presidential amnesty, which was finally granted in October 1953. He began campaigning with a view to standing in the legislative elections of 1956, or perhaps even with the aim of overthrowing his local rival, new mayor Jacques Chaban-Delmas. But everything came to a sudden end during an eventful political meeting held at the city’s “Athénée” meeting hall (although some sources suggest the venue may have been the Alhambra concert hall). Heckled and destabilised by Chaban supporters, at the end of his rally Marquet suffered a heart attack and died, aged 71.

All of which explains why the official public-domain acknowledgements of Adrien Marquet are few and far between: his name features on the list of mayors on a plaque outside Palais Rohan, the city hall, on Place Pey-Berland (as pictured right); his bust stands alongside those of fellow mayors in the Bordeaux city council’s meeting room; and that’s about it! But the subject does continue to fascinate: Marquet was the subject of an authoritative and exhaustive (but also slightly disjointed) 400-page biography penned by local academics Hubert Bonin, Bernard Lachaise and Françoise Taliano-Des Garets. When historian Franck Lafossas came across a suitcase packed with unseen archive documents, he too produced a revealing book. And an hour-long France 3 documentary about Marquet, directed by Barcha Bauer and narrated by Invisible Bordeaux acquaintance Michel Cardoze, was released in 2008 and can be viewed in its entirety on Youtube. It features some incredible archive photos and footage.

So, in this modern day and age, there can be no excuses for not knowing everything there is to know about the mysterious man who was mayor of Bordeaux for 19 pivotal years during the 20th century…

View the aforementioned documentary, "Adrien Marquet : de Jaurès à Pétain, les dérives d'une ambition"

Click here if video does not display properly on your device. > Find them on the Invisible Bordeaux map: Adrien Marquet's birthplace, 104 Cours Victor Hugo; Adrien Marquet's grave, Cimetière de la Chartreuse, Bordeaux.

> The books referred to above are "Adrien Marquet, les dérives d'une ambition" by Hubert Bonin, Bernard Lachaise and Françoise Taliano Des Garets; and "Adrien Marquet : secrets et souvenirs" by Franck Lafossas.