EMILY ESFAHANI SMITH

How suicide hurts us all.

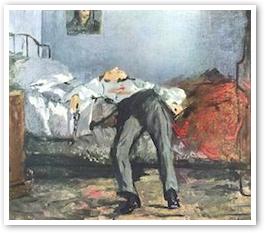

Édouard Manet, The Suicide, 1877–1881

Over the past few months, there have been several heartbreaking reminders of the rise of suicide across this nation, a topic I wrote about in my first “Manners & morals” column in October (“Life on the island”). The most high profile of these suicides was L’Wren Scott’s. The forty-nine-year-old fashion designer was found dead in her New York City apartment, reportedly bought for her by then-boyfriend Mick Jagger.

A week later, the New York City schools chancellor, Carmen Farina, convened a private meeting of principals to discuss the suicide epidemic among the city’s students. Thanks to the New York Post, which broke the story, we now know that suicides are on the rise among the city’s youth: two years ago, nine students committed suicide; last year, fourteen did; and already, four months into 2014, twelve have committed suicide in New York.

In March, volunteers gathered in Washington to plant 1,892 American flags on the National Mall commemorating each veteran who had committed suicide since the beginning of 2014. Do the math: that’s twenty-two veteran suicides a day. Another tragic figure: Since 2001, the year marking the beginning of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, more active-duty soldiers have killed themselves than have died in combat.

The rise in suicide has been accompanied by a loss of the moral questions that once surrounded it. G. K. Chesterton was one of our last full-throated critics of suicide. His insistence that suicide is immoral sounds strange to our individualistic ears: “Not only is suicide a sin, it is the sin,” Chesterton wrote: “It is the ultimate and absolute evil, the refusal to take an interest in existence; the refusal to take the oath of loyalty to life. The man who kills a man, kills a man. The man who kills himself, kills all men; as far as he is concerned he wipes out the world.” Chesterton goes on to say that the act of suicide is selfish: “A suicide is a man who cares so little for anything outside him, that he wants to see the last of everything.” It would be difficult to imagine anyone writing such a polemic today. We do not consider suicide the moral catastrophe that people like Chesterton once thought it was.

Rather, our contemporary culture treats suicide as a medical problem — a “public health concern,” as Joshua Rottman, a psychological researcher, recently told The Atlantic. According to his new research, religious and non-religious people have a moral bias against suicide, and the bias stems from “disgust reactions” they have when confronted with stories of suicide. Committing suicide, people think, taints the soul. To Rottman, this is a problem. These reactions are irrational and, therefore, harmful: “The million-dollar question,” Rottman says, is “how to de-stigmatize suicide as impure.” He went on to say, “That’s not to say that we should start thinking that suicide is perfectly OK, but I don’t think we should treat it as taboo (and therefore avoid bringing it up in polite conversation). Instead, we should engage with it as a public health concern and find ways to effectively increase prevention.” But Rottman is wrong to demoralize the notion of suicide. If we are serious about helping people overcome the dark nights of their souls, we must insist with Chesterton that suicide is a moral, not just a clinical, problem.

An important new book does just that. Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It by the poet and philosopher Jennifer Michael Hecht challenges our culture’s acceptance of suicides and reinvigorates the moral arguments against it. At a time when few philosophers or intellectuals are offering strong, compelling, secular arguments against suicide, Hecht’s book steps in as a reminder that our liberal stance toward suicide is relatively new, in fact quite radical, and should be unequivocally challenged. Partly an intellectual history and partly a polemic — a gentle one — against suicide, the book fills a hole in the cultural conversation about choosing to end one’s life. Hecht writes, “The arguments against suicide that I intend to revivify in public consciousness assert that suicide is wrong, that it harms the community, that it damages humanity, that it unfairly preempts your future self.”

Hecht reminds us that throughout history — in the West at least — there have always been strong social sanctions and philosophical arguments against suicide. Though the ancients for the most part wrote against suicide, those positions were advanced most forcefully by Christian thinkers, who viewed suicide as a sin — a violation of God’s moral law. Christian beliefs about suicide were articulated most clearly by St. Thomas Aquinas, who thought, as Hecht writes, that “Suicide is cruel to the community, it is cruel to oneself, and God has ordained against it.” Those who violated the moral law, by taking their own lives, faced a grisly posthumous fate. Their bodies would be tortured, dragged through the streets, their estates seized by the church, their families left impoverished.

This view began to evolve during the Enlightenment. The secular philosophers of that age, like David Hume and Baron d’Holbach, did everything they could to argue Christianity into philosophical irrelevance. One of the casualties in the war against religion was the moral sanction against suicide, which Hume associated, as Hecht points out, with “modern European superstition.” It was a classic case of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. To Hume and d’Holbach, suicide was a permissible way to escape suffering, and their justification was often chillingly inhumane. D’Holbach asks, “Besides, what assistance or what advantage can society promise to itself from a miserable wretch reduced to despair, from a misanthrope overwhelmed with grief, from a wretch tormented with remorse, who has no longer any motive to render himself useful to others, who has abandoned himself, and who finds no more interest in preserving his life?”

The pro-suicide view, which is “now a defining stance of secular culture, is a mistake and needs rethinking,” writes Hecht. It has led to moral confusion. The secular among us may reject Christianity and the Christian ideas about suicide — and certainly the medieval response to it — but that does not mean we should conclude that suicide is permissible. The secular argument against suicide has, after all, been championed by an impressive group of thinkers, from Kant to Durkheim to (the suicidal) Wittgenstein. As a culture, we have forgotten their arguments but we must revive and champion them in order to save suicidal people from the tyranny of their emotions. The suicidal person must be brought to realize that suffering is a natural and passing part of life, that he must persist, and that he lives not just for himself but for the sake of others.

The moral weight of Hecht’s argument becomes clear when we consider the far-reaching effects of suicide. They extend beyond the death of the suicide and the grief of his loved ones. Suicide, like an infectious disease, is contagious. When one person in a community ends his or her life, it is not uncommon to find other people following suit, creating what scientists call a “suicide cluster.” This is why, in a powerful rhetorical flourish, Hecht calls suicide “delayed” murder. When you decide to take your life, she argues, you are not only killing yourself, you are killing your neighbor down the street, your peer at school, your brother-in-arms.

The very idea of suicide can lead to self-murder. Goethe’s novella The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) — about a young man who kills himself when the woman he loves rejects him — set off a rash of copycat suicides in Europe when it was published. The “Werther effect,” as it is known, should make us pause and reflect on the way the media covers real suicides and the way artists and creators address suicide in their works. Hecht, to this end, cites a study from The New England Journal of Medicine about three movies with suicides as central aspects of the plot. The study “found that suicide increased after two, both of which concentrated their attention on the suicide victim. One movie that was not associated with a rise in the suicide rate concentrated on the grieving parents.” Ideas have consequences: “They can influence people both toward and away from death.” Hecht cites research showing that most people who tried and failed to commit suicide are grateful they failed. They do not make another attempt to end their lives and admit that “their initial attempt was an act of impulsivity.”

In my column last October, I pointed to research — from Durkheim and modern social science — showing that the rise of suicide has been accompanied by a rise in individualism. The role of the individual in society has changed dramatically since the Enlightenment. Before, the influence of the Judeo-Christian tradition in the West placed moral constraints on an individual’s will. Morality was organized around God’s will and our duties to the community — and suicide was considered an affront to both. Today, though, our sense of right and wrong is organized more around the individual’s experience than on the health of the community.

The popular movie Dead Poets Society (1989) is a good example of the modern and individualistic response to suicide. The film is about a group of high school seniors at an elite all-boys New England boarding school. The group’s ringleader, Neil, faces a common adolescent dilemma. His parents want him to go to medical school, but he wants to be an actor. Against his father’s wishes, Neil performs as Puck in the school’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, so his father decides to pull him out of the idyllic boarding school and send him to military school, which will better prepare him for Harvard and a career as a doctor. When Neil returns to his home, he is in emotional turmoil. He thinks his life is over. He thinks he won’t be able to live out his dream of being an actor. His self-righteous solution to his problem is to kill himself in the home of his parents, who discover his body later that night.

Regrettably, the story romanticizes his suicide. Neil puts on a crown of thorns before he ends his life, drawing a spurious connection between his ultimate act of willfulness and Christ’s acquiescence to his Father’s will. The teenage boy, we are meant to conclude, is a victim — and his father is the villain, responsible for his death and deserving of the suffering he feels when he sees his dead child. The film invites us to sympathize with Neil’s plight. Neil’s death is meant to be an expression of freedom, an escape from misery, suffering, and the other barriers that would prevent him from living his life as he would like to. But the fact is that Neil’s decision is rash and, above all, selfish. Unlike Christ, he does not lay down his life out of love of others; rather, his suicide is an act of revenge. Yet we are meant to conclude that he is some sort of hero, who dies because the world is amiss and he cannot fulfill his artistic ideal.

Hecht urges us to “retire the idea that we are each free to end our lives.” Here Hecht is really insisting that we rethink the individual’s relationship to his or her community. Suicide, which may end the misery of the individual, leads to untold amounts of misery in the community. Ending one’s life is therefore not just a personal choice whose effects are borne only by the dead. It renders a profound judgment against the world we all share together.

Our attitude toward suicide says a lot about how we value life and the communities that sustain us. It shouldn’t surprise us that suicide has gained acceptance in our culture; our communities are dissolving, and the individual, free from many of the traditional constraints, is considered the master of his own fate. Though there are certainly cases when death is justly considered a deliverance from suffering, it’s time to reconsider our belief that, as individuals, we are free to choose the time and place of that deliverance. As Hecht writes, “The meaning of life is bigger than the individual.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Emily Esfahani Smith. “The catastrophe of suicide.” The New Criterion (May, 2014).

Reprinted with permission of the author, Emily Esfahani Smith.

The New Criterion, founded in 1982, is a monthly review of the arts and intellectual life. Written with great verve, clarity, and wit, The New Criterionhas emerged as America’s foremost voice of critical dissent in the culture wars now raging throughout the Western world. A staunch defender of the values of high culture, The New Criterion is also an articulate scourge of artistic mediocrity and intellectual mendacity wherever they are found: in the universities, the art galleries, the media, the concert halls, the theater, and elsewhere.

THE AUTHOR

Emily Esfahani Smith is the Managing Editor of The New Criterion. She writes about culture, relationships, and psychology. Her writing has appeared at The Atlantic, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, and other publications. She serves as the managing editor of the Hoover Institution’s Defining Ideas. A Senior Fellow at the Independent Women’s Forum, she is also the editor-in-chief of Acculturated, a blog about the virtues and vices of pop culture. Born in Zurich, Switzerland, Emily grew up in Montreal, Canada, and now lives in New York City. She graduated from Dartmouth College, where she was editor of The Dartmouth Review

Copyright © 2014 The New Criterion