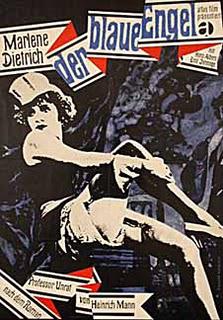

What was it about the Germans that made their initial forays into talkies the high-water marks of the new format? If anything, the German film style to that point was the one best suited to silence, all Expressionistic imagery crafting endless depth out of jagged set design, shadowplay and graceful camera work. Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel contains many visual cues that tie it to the national cinema of the past—angular backdrops of villages, impossibly cramped apartments filled with minute detail—but his greatest coup is his incorporation of sound into the image in such a way as to enhance the atmosphere, adding another dimension to artistic control.

What was it about the Germans that made their initial forays into talkies the high-water marks of the new format? If anything, the German film style to that point was the one best suited to silence, all Expressionistic imagery crafting endless depth out of jagged set design, shadowplay and graceful camera work. Josef von Sternberg's The Blue Angel contains many visual cues that tie it to the national cinema of the past—angular backdrops of villages, impossibly cramped apartments filled with minute detail—but his greatest coup is his incorporation of sound into the image in such a way as to enhance the atmosphere, adding another dimension to artistic control.The director's exacting perfectionism turns the story of Immanuel Rath (Emil Jannings), an uptight teacher at a preparatory high school who gets lured by the seductions of Weimar Germany, into a stylistic smorgasbord of crisp, static imagery (this was early sound cinema after all) that from the first moment suggest a slight separation from reality that grows into a gulf as the film progresses. Jannings, portly and mannered, nevertheless betrays flashes of expressive acting early on that show a restlessness and a madness within him long before the head-spinning perfection of Marlene Dietrich's legs tilts him off his axis.

Jannings was a master of silent cinema, and he clearly respected von Sternberg so much that he reconciled with the director after the two had an intense falling-out over The Last Command. In a film filled with detailed sets that communicate social disarray (or, conversely, the lingering regimentation of the nation's youth in its schools), Jannings is the most dynamic element of the mise-en-scène, always adjusting his large frame to fit into the frame or to further emphasize his remove from everything else around him. His comical mustache, grown out to the point that it is not easily tamed, flaps with abandon and twitches with anticipation as Rath's grasp on decorum slips. After he follows his miscreant students into the Blue Angel nightclub and gets an eyeful of Lola Lola (Dietrich), that mustache is becomes the last thing Immanuel cannot control.

Who can blame him? Dietrich pops off the screen as Lola, her smile more blinding than the spotlight she shines on Immanuel when he first come into the Blue Angel. Despite her sultry presence, Dietrich also gives off a kindness that isn't a trap, even if it makes Immanuel so dizzy he ends up destroying himself. Seemingly anyone can wander backstage after her, and the other upstanding gentlemen of the community are so smitten with Lola that Rath, who frets about his reputation, receives only admiring from support from the people who see him with her. Jannings is the film's centerpiece, but it's no wonder von Sternberg teamed up with Dietrich again. You don't let your only film with a talent like that put her in a supporting role.

Jannings' well-modulated progression of insanity and unchecked desire aligns with von Sternberg's direction, which is also pristine and fussy but is just outside of realism from its opening scans over cutout village dwellings. Immanuel's apartment is a place of disarray, cluttered with books that look dust-covered with lack of use. The Blue Angel, like other nightclubs the film will show, is tiny and vaguely depressing but feels vast, as it contains the last vestiges of cheer, however ironic, in the impoverished postwar nation. The hall, though containing no more than a few dozen people, nevertheless looks cramped, and von Sternberg has the sound amped up to make a dingy dive sound like Madison Square Garden.

So effective is von Sternberg's use of audio throughout the film that, before even getting to the dialogue, von Sternberg has used diegetic sounds and music to create such a mood that the sound sounds more natural than other early users of the technology, even as the director uses it to artificial and artistic effect. Amusingly, von Sternberg finds ways to cut out the sound, whether by having Rath's songbird die in its cage at the start or by closing a window during a test so the sound of singing girls is instantly silenced in the room. This is a repeated device, sounds always being silenced entirely with a closed door, sealing off worlds from each other and giving off a sense of isolation that heightens the later blossoming of desire. Yet by creating patches of silence, von Sternberg suggests that the supposed gimmick really does make the experience more realistic, and he makes the silent portions the ones that feel odd and disconnected.

The Blue Angel proves a remarkably conservative film, tearing down a man through base lust until he's become a horrible perversion of himself. Yet, whether or not von Sternberg would acknowledge it, the arrogance Rath builds on a foundation of sand turns him into a personification of Weimar Germany, an entity proud of itself for nothing as it sinks further into squalor and vice. Even the cabaret tunes have an air of portent to them, lonely and morose even at their most drunkenly exuberant. It's telling that Rath, already tempted, completely falls for Dietrich when she sings a slow, sad song that takes the smoky seduction of nightclub cabaret and slows it to a crawl, like a music box winding down. (Von Sternberg only makes this connection clearer when he shows Rath waking up the next morning in Lola's bed and playing with a music box on her nightstand.) Rath's eventual mental collapse prefigures the madness that would sweep Hitler to power, an idea that Fritz Lang would flesh out more the following year with his own, far grittier look into Germany's sinful underbelly. The Blue Angel may not reach the same heights (lows?) as M, but it has held up just as well.