Book Review by Jane V: Bond meets Biggles – way out of my comfort zone. But what interested me most about this story is the speed with which reporting on contemporary events, as they happened, was written up and published in no more than three and a half months. Wheatley must have written fast (376 pages). I read the story with my Liddell Hart’s History of the Second World War in the other hand and the date of the last event I can verify reported in the book is 17 June 1940 when Marshal Petain asks Germany for an armistice. (There is a slightly paraphrased reproduction of Churchill’s 4 July speech, ‘WE have become the sole champion now in arms to defend the world cause’ forms the last paragraph of the book so was likely added at page proof stage.) When you think what a laborious task type setting was in those days, placing letter by letter in a form, and then the proof reading – galley proofs then page proofs; the design and printing of a cover; the printing of the text and then the binding and finally delivery to a warehouse and then out to shops when, by September, Britain was under almost continual bombardment, it is a truly amazing feat. (7 September 1940 blitzkrieg on London begins.)

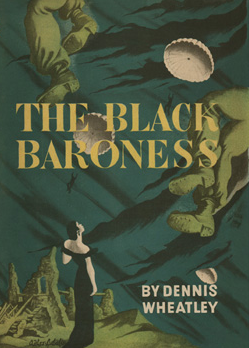

Cover of the first edition

Cover of the first edition

The eponymous villain, the Black Baroness, doesn’t appear until almost halfway through the book and serves only to progress Sallust’s adventures through Europe. There is, however, an interesting exchange between Sallust and the Baroness when he finally catches up with her in her villa in the south of France. Sallust levels the charge of traitor and Nazi sympathiser at her but Wheatley gives her the chance to put her own view of her mission which is to save France from a decadent aristocracy and to make France a more egalitarian state for everyone. (This rings somewhat false as this lady has sped south with metal boxes full of secret papers and her personal jewels, fur coats and old masters!) But it seems that everyone who could lived well in those days. Wheatley’s family were wine merchants and Sallust and friends imbibe enormous amounts of named fine wine and champagne throughout the story. It seems always to be available wherever Sallust is.

To an extent Wheatley’s book reads as resolve stiffening propaganda for the Brits. He doesn’t restrain himself from criticizing the powers that be who in early 1940 seem not to be taking Hitler’s war plan seriously enough. There is disgusted criticism of Baldwin’s attempt at appeasement, of course, and of the generals responsible for Britain’s’ security, the general lack of preparedness for war and the blithe way that British society was gaily pursuing its comfortable life. ‘Old England seemed to be jogging along as though the war were just a rather remote and tiresome business.’

‘. . . all sorts of . . . dangerous bodies composed of rogues, cranks, half-wits and actual traitors were still allowed to publish as much subversive literature as they liked and to advise cowards to evade military service on the plea that they were conscientious objectors.

’‘Weak-kneed government was being intimidated by a handful of irresponsible MPs into permitting Hitler’s Fifth Column in England absolute freedom to contaminate thousands of misguided idealists . . ‘

Strong language indeed! This is Wheatley speaking through Sallust, surely? Wheatley goes on to write that Sallust would have liked to have been given Gestapo powers in the Home Office for half a day. He would sign death warrants of spies, have them shot and their dead bodies photographed ‘to intimidate the others’. Methods worthy of the Gestapo whom he effects to abhor. But evidence of how strongly Sallust’s inventor felt as he was writing.

Germans, of course, have to be described as ‘fat, ugly, vulgar’. ‘ . . reddish, protruding ears of a host of blond, waxy-faced, pot-bellied Huns.’ Except Sallust’s love Erika who because she is a good German is introduced to us at the beginning of the story as ‘golden-haired and very beautiful. Her proud profile and lazy grace with which she half-reclined . . marked her out at once as an aristocrat.’ That’s alright then! High birth equals noble character and attractive physique. Is there a touch of eugenics here? There is one other German whom Sallust admires. This is von Zeigler whom Sallust meets in Norway when Sallust is posing as a German national. Sallust and von Zeigler deal nobly and in gentlemanly fashion with each other, and part on a hand-shake and a wish for good luck, even after Sallust has been exposed as a Briton.

The descriptions of women and women’s minds are treated in such a way as to shock the modern (female) reader. Basically – with a few exceptions, Erika, the Black Baroness – women are portrayed as fluffy, unimaginative, limited creatures who want only security of marriage and children. Wheatley allows himself an excursion into describing the differences between men and women. Having been poisoned by the Black Baroness Sallust is in the care of a French nurse (pretty of course). He gets up before he is recovered and is scolded by the nurse.

‘What children men are! They think there is no limit to their strength, and that . . . the world will cease to turn if for one moment they must give up the new games with which they amuse themselves. . . . If women ruled the world your nasty dangerous toys would be taken from you for good and all and then there would be some peace and happiness for a change.’

To which Sallust replies in thought only that perhaps the world would be a better place if, ‘like the ants and bees, the human race were content to live under a matriarchy. Where there was no progress, no ambition, but work and food for all; yet . . he could not believe that, because if one rejected all hope of advancement at the price of permanent peace it meant the death of the spirit, by the possession of which alone man differs from insects and animals.’

A degree of willing suspension of disbelief is called for as you read these adventures. Sallust has implausible escapes and unlikely strokes of good luck. He manages to evade every bullet, never seems to lose his pistol no matter how many ditches he has been obliged to throw himself into. He always has money in whatever currency is relevant to the country he is in to pay for sustenance bought from little cafés which still seem to be standing and trading in the midst of mayhem. We know he will survive, as we know James Bond will, because they are in a series of stories which run and run. The Black Baroness is a ripping read I suppose, if you like Boy’s Own stuff.