"You're a bit depressed for a man on his birthday!"

William Friedkin's The Birthday Party (1968) adapts Harold Pinter's absurdist play into a challenging film. Despite Friedkin's efforts, it's such an elusive work that cinema doesn't quite seem appropriate.Stanley Webber (Robert Shaw) is a musician boarding with an elderly couple, Meg (Dandy Nichols) and Petey (Moultrie Kelsall) at a seaside resort. Two new boarders arrive: Goldberg (Sydney Tafler), a chatty businessman, and McCann (Patrick Magee), a hulking criminal. Meg convinces them to throw Stanley a birthday party, despite Stanley's protests that it's not his birthday. But the guests have hidden motives related to Stanley's past.

The Birthday Party is primarily an exercise in cruelty. Pinter's characters conceal daggers within banal dialogue, escalating disagreements into savage conflicts. Stanley and Meg argue viciously over cornflakes and coffee; a blindman's bluff game begets destruction. Every tic, grimace and phrasing figures in a mind game, each character jousting for supremacy. It's Beckett mated to Strindberg, absurd and caustic at once.

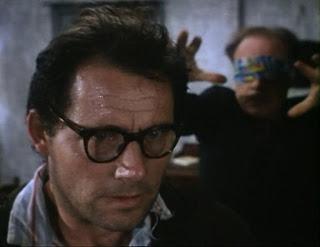

Aside from muted bookends, Friedkin keeps Party within Stanley's cluttered flat. He barrages us with disorienting camerawork: long takes, jarring close-ups, reverse zooms, monochrome shots and photographic negatives. Denys Cooper's camera lingers on greasy breakfasts, cluttered sinks and filthy dens, all shabby and grotesque. It's hammered home with an abrasive soundscape: clattering pans, cacophonous knocking, McCann interminably tearing newspapers.

The Birthday Party's circular convolutions occasionally wear thin. Goldberg's doom-laden insinuations alternate with trite symbols (Stanley's toy drum and broken glasses) and misplaced silliness (Meg's obsession with her party dress). Pinter maddeningly allows tension to fizzle in repeated scenes and a flat non-ending. Both gripping and exhausting, Party makes viewers fumble for explanations.

Robert Shaw gives a shambling, desperate performance. Emoting in a strangled, nervy voice, sporting ragged shirts and threadbare sweaters, Shaw exudes a tortured veneer, far removed from his macho persona. Sydney Tafler's ingratiating menace and Patrick Magee's gloomy incomprehension provide effective counterpoint. Dandy Nichols is an amiable ditz, absorbed in yet oblivious to the turmoil.

Harold Pinter fit his quirks into Joseph Losey's The Servant (1963) and The Go-Between (1971), where muted menace underpins navigable narratives. In contrast, The Birthday Party's inscrutable core remains undiluted. Cineastes must decide whether deciphering it's worth the effort.