For many years I’ve been interested in modelling the extinction dynamics of megafauna. Apart from co-authoring a few demographically simplified (or largely demographically free) models about how megafauna species could have gone extinct, I have never really tried to capture the full nuances of long-extinct species within a fully structured demographic framework.

That is, until now.

But how do you get the life-history data of an extinct animal that was never directly measured. Surely, things like survival, reproductive output, longevity and even environmental carrying capacity are impossible to discern, and aren’t these necessary for a stage-structured demographic model?

The answer to the first part of that question “it’s possible”, and to the second, it’s “yes”. The most important bit of information we palaeo modellers need to construct something that’s ecologically plausible for an extinct species is an estimate of body mass. Thankfully, palaeontologists are very good at estimating the mass of the things they dig up (with the associated caveats, of course). From such estimates, we can reconstruct everything from equilibrium densities, maximum rate of population growth, age at first breeding, and longevity.

But it’s more complicated than that, of course. In Australia anyway, we’re largely dealing with marsupials (and some monotremes), and they have a rather different life-history mode than most placentals. We therefore have to ‘correct’ the life-history estimates derived from living placental species. Thankfully, evolutionary biologists and ecologists have ways to do that too.

eyes, with a single large toe on each foot (reduced from the more normal count of four). Each forelimb had two long, clawed fingers that would have been used to bring leafy branches within reach.

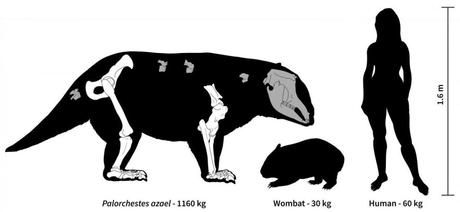

So with a battery of ecological, demographic, and evolutionary tools, we can now create reasonable stochastic-demographic models for long-gone species, like wombat-like creatures as big as cars, birds more than two metres tall, and lizards more than seven metres long that once roamed the Australian continent.

Ancient clues, in the shape of fossils and archaeological evidence of varying quality scattered across Australia, have formed the basis of several hypotheses about the fate of megafauna that vanished during a peak about 42,000 years ago from the ancient continent of Sahul, comprising mainland Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea and neighbouring islands.

There is a growing consensus that multiple factors were at play, including climate change, the impact of people on the environment, and access to freshwater sources.

Just published in the open-access journal eLife, our latest CABAH paper applies these approaches to assess how susceptible different species were to extinction – and what it means for the survival of species today.

Using various characteristics such as body size, weight, lifespan, survival rate, and fertility, we (Chris Johnson, John Llewelyn, Vera Weisbecker, Giovanni Strona, Frédérik Saltré & me) created population simulation models to predict the likelihood of these species surviving under different types of environmental disturbance.

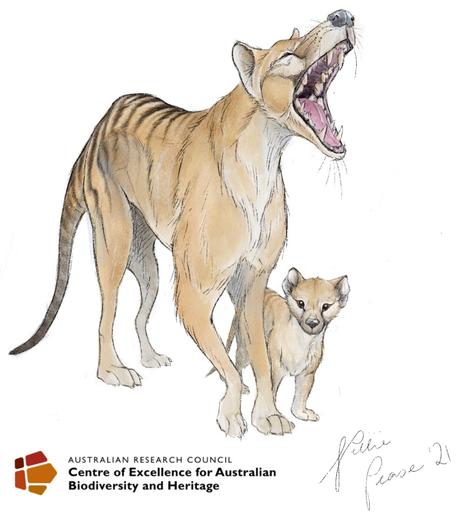

Simulations included everything from increasing droughts to increasing hunting pressure to see which species of 13 extinct megafauna (genera: Diprotodon, Palorchestes, Zygomaturus, Phascolonus, Procoptodon, Sthenurus, Protemnodon, Simosthenurus, Metasthenurus, Genyornis, Thylacoleo, Thylacinus, Megalibgwilia), as well as 8 comparative species still alive today (Vombatus, Osphranter, Notamacropus, Dromaius, Alectura, Sarcophilus, Dasyurus, Tachyglossus), had the highest chances of surviving.

We compared the results to what we know about the timing of extinction for different megafauna species derived from dated fossil records. We expected to confirm that the most extinction-prone species were the first species to go extinct – but that wasn’t necessarily the case.

While we did find that slower-growing species with lower fertility, like the rhino-sized wombat relative Diprotodon, were generally more susceptible to extinction than more-fecund species like the marsupial ‘tiger’ thylacine, the relative susceptibility rank across species did not match the timing of their extinctions recorded in the fossil record.

Indeed, we found no clear relationship between a species’ inherent vulnerability to extinction — such as being slower and heavier and/or slower to reproduce — and the timing of its extinction in the fossil record.

In fact, we found that most of the living species used for comparison — such as short-beaked echidnas, emus, brush turkeys, and common wombats — were more susceptible on average than their now-extinct counterparts.

We therefore concluded that the true extinction cascade was likely the result of complex, localised scenarios, including impacts of regional climate variation, and different pressures from people across regions.

The relative speed of different species to escape hunters, as well as whether or not a species dug protective burrows, also likely contributed to the mismatch between extinction susceptibility and timing.

For example, fast-hopping red kangaroos still alive today might have had an escape advantage over some of the slower-striding short-faced kangaroos that went extinct. Small wombats that dug burrows might also have been more difficult for people to hunt than the bigger, non-burrowing megafauna.

We determined that overall the kangaroo species were the least-susceptible to extinction based on their biology, followed by the monotremes (echidnas), and the giant ‘wombat’ species. Interestingly, the large, flightless birds, like emu and the giant mihirung ‘thunderbird’ Genyornis, had the highest susceptibilities.

Our results support the notion that extinction risk can be high across all body sizes depending on a species’ particular ecology, meaning that predicting future extinctions from climate change and human impacts aren’t always straightforward based on the first principles of biology.