Much as I desired some kind of return for silent filmmaking in the 21st century, Michel Hazanavicius' The Artist does not resemble a silent picture so much as a talkie with the audio track removed. Lacking all the propulsion of silent cinema, the capacity for rich visual storytelling that seemed fast ay any speed, The Artist lethargically moves through its pastiche. As a billet-doux, the film is sufficiently earnest to be charming, but it never displays any particular insight into the silent era, making even its homage thin.

Much as I desired some kind of return for silent filmmaking in the 21st century, Michel Hazanavicius' The Artist does not resemble a silent picture so much as a talkie with the audio track removed. Lacking all the propulsion of silent cinema, the capacity for rich visual storytelling that seemed fast ay any speed, The Artist lethargically moves through its pastiche. As a billet-doux, the film is sufficiently earnest to be charming, but it never displays any particular insight into the silent era, making even its homage thin.But then, Hazanavicius' jumping-off point appears not to be the silents themselves so much as Singin' in the Rain, the 1952 masterpiece that also dealt with the change from silents to talkies. The Artist is the flip-side of that, not about the song-and-dance people who made up for the camera's loss of lyricism but those on the other side of the spectrum, unable to adapt to the new format. In a sense, the hero of The Artist is Lina Lamont, albeit more likable and earnest. But if Kelly and Donen's work was a sincere, if teasing, testament to the event that gave their own careers a boost, The Artist too often feels suffocatingly nostalgic in a lecturing way, even as it does not capture the tone the silents.

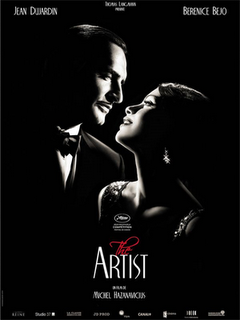

Opening at the premiere of the new George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) film, The Artist shows the final twilight hurrah of this Douglas Fairbanks-esque silent star, his picture playing to a packed house as laughs and cheers roar soundlessly from the crowd's throats. On- and off-screen, Valentin is a mug, his gigawatt smile powering all of Tinseltown and his multiple curtain calls but another chance to charm the crowd with physical tricks performed with his trusty dog, whom he clearly considers more of a co-star than the film's leading lady. Walking out of the theater, he bumps into a young woman, Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), whose frame-halting looks get her on the cover of Variety, burying the actual review. Peppy takes the press to the studios, where she gets her way onto the set of George's new movie and begins a meteoric rise.

So far, so good. But when Hazanavicius jumps forward two years to 1929, George finds his world turned upside down. With talkies now the rage, the head of the studio (John Goodman) shuts down production of silents, but George refuses to accept this defeat. The actor suddenly becomes a director, bankrolling his own silent adventure movie, a garishly outdated affair even as seen during its construction. When George and his dog enter the theater on opening night, they increase the audience size by a third. One block over, the marquee that once bore George's name in massive letters now sports Peppy's fresh face as audiences flock to this new talkie bombshell. What had been a light, if still stodgy, love letter to silent cinema now becomes an embittered, morose tale of forgotten talent.

But not even this tone, which lasts up until the film's final few minutes, carries any real heft. Part of this isn't the director's fault: he's done a good enough job of capturing the general beats of silent melodrama that anyone can guess how the story will resolve. But the unimaginative framing, which shows off the sterling set design but does little to generate mood through the visuals, leaves this section, covering the second and nearly all of the third acts, hopelessly flat. For a silent feature, the characters often have to "voice" their feelings, even as the actors routinely demonstrate that they could do it all on their own if the camera pulled back and let them loose.

But what makes The Artist all the more frustrating are the instances where Hazanavicius clearly demonstrates a skill above mere competence. A scene of Peppy, the top half of her body obscured by a setpiece, engaging in a dance-off with George is an early highlight of pure elation, a simple but playful exchange between two people already flirting each other before even making eye contact. Likewise, an all-too-brief moment of Peppy gently, lovingly acting out her budding love for George with his empty suit jacket, threading one of her arms through a sleeve to make this ghost embrace her, is so well-performed, delicate and touching that its almost immediate interruption is the film's most painful seconds. And when all is well again and George gets his Hollywood ending at the end, the dance sequence between the two leads is so effervescent that it nearly excuses the entire hour that preceded it.

"If that's the future, you can have it!" George says of the encroaching talkies shortly before his fall, but it's hard to see what's even so different about those initial talkies that threatened an entire way of filmmaking and gave birth to an all-new one, given how uniform the movies within the movie are to the film itself. There is something genuinely exciting about a silent film being a hit with festival and limited-release crowds, not to mention heading the Oscar pack. But it would be even more thrilling if The Artist actually felt like a true silent, classic or modern, instead of a typical Oscar movie with a light twist.