Now that I've just put fire on the table, though a segment from Disney's original animated version of The Jungle Book, I might as well go whole hog. At the center of Nina Paley's Sita Sings the Blues there is an astonishing 3-minute sequence depicting a fire ritual, the Agni Pariksha. Here it is:

I described that sequence in some detail in something I published in 2014, Cultural Evolution: A Vehicle for Cooperative Interaction Between the Sciences and the Humanities. I've also interviewed Nina about that segment, Nina Paley on the Agni Pariksha, where she comments on the segment as we move through it from beginning to end. I've also provided some descriptive information on the sequence.

What follows is an edited version of the presentation in the cultural evolution paper.

* * * * *

Nina Paley’s animated film, Sita Sings the Blues, revises and retells the story of Rama and Sita from the Ramayana, one of the classic texts of Hinduism. Paley tells Sita’s story in three different ways: 1) in a series of vignettes set to songs recorded by Annette Hanshaw in the 1920s and which is animated in a very “cartoony” style; 2) in a series of scenes based on paintings Paley did in imitation of 18th Century Rajput miniatures and on collages based on what appears to be calendar and greeting-card art, and 3) through voice-over dialog among three Indian-Americans talking about the Ramayana and realized on-screen as three Indonesian shadow puppets. The multiplicity of this story, its many sources – which I’ve only hinted at in this brief description – is deliberately built-in to the visual and audio texture of the film.

Let's look at the film itself. What does it look like on the screen? How do we describe it? What features are important to the film’s effect, and which are incidental? These are important and difficult questions and I can do no more than indicate what’s entailed.

In particular, I want to examine the Agni Pariksha segment, which is unlike anything other segment in the film. In the Ramayana Sita had to prove her fidelity to Rama in a trial by fire. She throws herself into the flames and is rescued by Agni, the fire deity, thereby establishing her purity.

Paley has placed this segment somewhat after the middle of the film at the point immediately after Nina, her alter ego in the film, learns that her husband wants a divorce. On the sound track we hear her heart thumping away while we see it pulsing (a stylized red heart) and finally breaking. At that point Nina screams, the virtual camera zooms into her wide-open mouth, and we’re into the segment, which is basically a solo dance amid flames.

The role of Sita is danced by Reena Shah, who voices Sita and who also sings the lyrics, written in Hindi by her mother, Laxmi Shah. This is the only place in the film where we hear Hindi and the only place where we see live action, sort of. Paley videotaped Shah dancing before a green screen and then hand-traced Shah’s movements into the film.

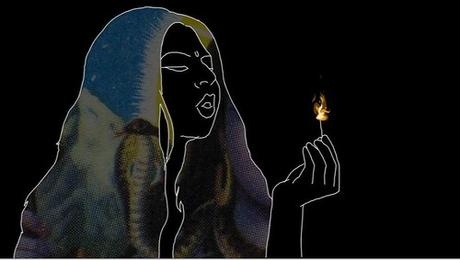

Rather than attempting to describe the entire three-minute segment, which could easily go on and on – “a picture is worth thousand words” and this film packs a lot of them into 180 seconds. Instead, I’ll concentrate on a few frames. The following two frames are from the beginning and the end of the segment, respectively. We see Sita in white outline against a black background, but her hair has some color fill (collaged in) in the ending segment, but not the beginning.

In both frames she is holding lighted match. She lit the match at the opening of the segment and then dropped it, lighting the fire beneath her. At the end she blows the match out, ending the segment. Thus there is a bit of visual continuity between the opening and ending segments. At the same time the final act, in effect, reverses the opening one. The opening act took Sita into the fire; the closing act brings her out of it and back into the world.

Is this a rite de passage? (Of course it is, of course.) For who? Sita, Nina, us? Of what kind, from what to what?

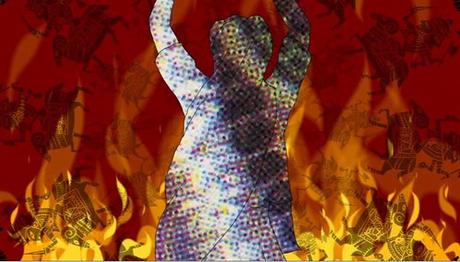

Now consider these three frames, which come one after the other in the film:

The backgrounds are pretty much the same, which is what you would expect from such closely spaced frames. But look at Sita in the center. Her outline is not quite the same from one frame to the next, for she’s spinning counter-clockwise at a pretty good rate; but her overall visual mass remains in the same position within the frame. The texture filling her form, however, differs radically from one frame to the next. All three body fills are half-tone images magnified to the point where the individual dots are visible, but I can’t make out identity of the material in either the first frame or the third. The second image is the head of a woman.

Paley uses this technique throughout the segment. None of the collage elements is on the screen for more than a fraction of a second. You can identify some of the images, but not most of them. It is obvious that she’s showing lots of different things mostly through Sita’s form, but through other elements of the segment as well.

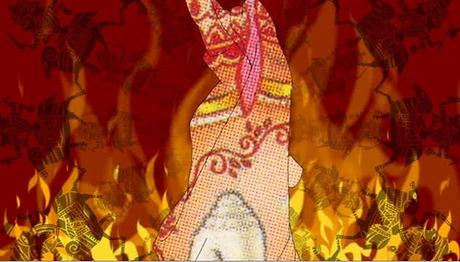

Now look at Sita in this next frame, to the left. Her outline, in black, is decoupled from the texture-filling forms, one for her hair (yellow-green), one for her body (a warm medium brown) and still others for her eyes. Paley does this for about six seconds. What’s this about?

If you’ve been reading visual neuroscience you may note that fill and outline are handled in different systems, as is motion. So Paley is “manipulating” those systems, which is interesting. But that doesn’t tell us why she’s doing it? Because she can, and it’s interesting? Certainly, but is that all?

Before I hazard a guess I want to state that the most important thing, at this point, is simply to describe what’s going on. Without that description, nothing else can be done.

So, why’s she doing it? Because it’s different from every other segment in the film, including the two segments that also depict the Agni Pariksha. One of those is set to Annette Hanshaw’s performance of “Mean to Me” while the other is set to her performance of “I’ve Got a Feelin’ I’m Fallin’.” In both of those cases the visual style is Paley’s old-time “cartoony” style, which she uses for all the Hanshaw performances. That is to say, those ritual enactments are not visually different from any other events in the Hanshaw version of the Sita story.

Any anthropologist will tell you that rituals are about transformation (e.g. van Gennup 1960); some literary critics will tell you that as well (e.g. Frye 1965, Barber 1959). By making this segment visually different from anything else in the film Paley is giving the film itself a ritual dimension – though the part of me that is a child of the 60s is thinking “altered state of consciousness” (cf. Fischer 1975). She’s not merely showing a ritual, depicting one in the film; she is inviting us to enact a ritual by experiencing the visual world in a way that is radically different from what we experience anywhere else in the film. This segment of the film IS ritual.

Now, if we wish, we can begin thinking about what happens in the nervous system in this segment that is different from every other segment in the film. In the annoying manner of math textbooks, however, I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.