Introduction

Of course, herein lies precisely what the Interwebs didn’t need: another write up of the Academy Award contenders for Best Picture of 2011. To which I say: fair point. This, however, was one of the first years in a while that I can actually say that I saw ALL of the Best Picture nominees (which I think is pretty impressive…since there’s now NINE of them), and I did so expressly for the purpose of being able to discuss them here on the site. Unfortunately, given the fact my schedule and personal commitments haven’t allowed me to do the full reviews I’m usually partial to doing, penning this overview is essentially my way of doing the next best thing.

Two caveats: First, this is not me handicapping the Oscars. I generally only watch them out of obligation, and after last year’s Hathaway/Franco debacle I have absolutely no desire to watch them this year (and those personal commitments will forbid it, anyway). I will comment on whether they deserved consideration, and I’ll make my pick of what I think should win and what I think will (since they’re not the same), but that’s pretty much it. Secondly, I myself won’t be doing any particular kind of ranking of this list (it’s presented in alphabetical order, as is standard) or otherwise doing my personal ranking of my favorite films of the year or anything like that. I’m personally not one for that kind of thing, and I generally feel such lists are defined almost as much by genre biases and false perceptions of import (the always ludicrous “movies” vs. “films” comparison) as anything else. In the end, this is basically my way of doing a bunch of my “Antiscribe Appraisals” in short form since I don’t really have the chance to do them in long (though the one for The Artist: pretty long). Of course, in some cases, I already did full reviews of those films, and will link to them where appropriate.

And with that, the nominees are…

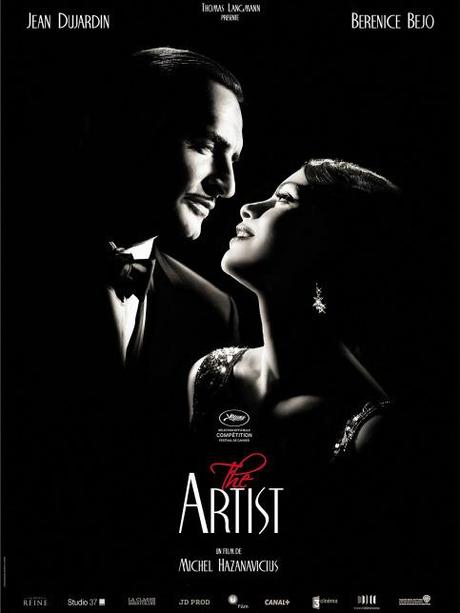

The Artist

Probably the most publicized of the Best Picture nominees, and with the Weinstein Co.’s lobbying machine behind it, The Artist is probably the film with the most momentum this year to win this category, and probably several others (though, sadly, nothing for Uggie, the film’s canine star). Besides that, it is also one of the best reviewed films of the year, at least by mainstream critics, and probably one of the most admired by audiences that have seen it. And I’ll admit, though I generally prefer to be all antithetical and stuff, I thought it was pretty fantastic, too. The Artist is a thoroughly entertaining, amusing, and touching film with a very nice aesthetic and commercial hook: an old-fashioned silent film, except it was made in the present day! Wow!

Though I’m being slightly sarcastic, I’ve been kind of surprised to discover through peoples’ anecdotes and my own observations that the idea of presenting a silent film in this day and age was more daring than I would have otherwise thought. In fact, some people in the theater I saw it in actually walked out a few minutes in, and I’ve spoken to people who suddenly lose all interest in it when I’ve mentioned that it’s silent. Of course it has also, to a much greater degree, been the recipient of a great deal of positive word of mouth. Was it really the Best Picture of the year, though?

In answering, I’m going to do something slightly different in discussing The Artist. Instead of heaping the kind of ebullient praise that has been pretty widespread, such as emphasizing the boundless talent and effortless charm of Jean Dujardin, who plays the title character – a silent movie star unable to transition to the world of “talking pictures” – or the sheer luminosity of Bérénice Bejo as the younger ingénue who loves him, I’m going to focus my thoughts on what I’ve perceived to be some of the different schools of thought that I’ve seen directed toward the film.

They're magnificent...enough said.

Naturally, the largest and most vocal group consists of those that endorse the movie wholeheartedly, viewing it for its entertaining qualities, the excellence of its craftsmanship and its performances, and as a “loving ode” to silent cinema. Its natural then, that the majority of film critics, themselves devotees to the glory and wonder of cinema, have certainly been adhering to this field of thought. After the supporters are those that give the film reserved praise; who basically state “Yeah, it was good…but it wasn’t THAT good.” There are then, however, the outright detractors, who are either unimpressed by its antiquated aesthetic or, conversely, are devotees to silent cinema (who are quick to emphasize, correctly, that cinema was never “silent” in any true appreciable sense) who find the film a poor example of the cinema they champion (many of the latter happen to fall into the scholarly category).

Toward the “devotee” perspective, while I personally very much enjoyed the film for its qualities, I do think it has suffered a pronounced surfeit of praise. The film is a fine and effective mix of hilarious comedy, touching melodrama, and enthralling romance that stands as a great testament to the universality of cinema, given that it is performed by French leads from a French writer/director, but otherwise set in the United States and aided by American film craftsmanship and Hollywood’s own vaunted legacy. But while it is excellent, that doesn’t necessarily make it a masterpiece; if it maintains past its initial novelty wearing off, than that will be the true test of its greatness. Right now, despite all of the obvious narrative similarities to it, it’s not Singin’ in the Rain yet.

"The Artist" is pretty easy to love...though not for everybody.

Naturally, this may sound as though I adhere to those that display reserved praise, but I feel the film was better than those of that perspective give it credit for being, and is absolutely worthy of being an Oscar contender; and if I learn, indeed, that it does win as most expect, I will hardly be upset about it.

Then there are the detractors, and in both cases, I do see their point. Looking at it through a more “modern” perspective, there are elements of The Artist, especially in the plotting, that may feel somewhat hackneyed, hokey, and wholly unrealistic. This is, of course, by the design of writer/director Michel Hazanavicius, but nonetheless, I see their perspective, since they are adhering to critical standards that, if broadly applied, are justifiably used to crucify other, lesser films. In this case, though, it has to be viewed as being reflective of its narrative, melodramatic tone and the storytelling style it’s paying homage to. For certain, though, if you’re the type of person who’s going to roll their eyes when the hero’s dog (played by the aforementioned Uggie) saves the day…The Artist will perhaps not be the film for you. Of course, if you’re also otherwise one of those people who view an absence of spoken dialog and/or the use of black and white as inherently detrimental to a film’s quality, than cinema itself probably just isn’t for you, either.

The star of the film, along with his human sidekick.

Finally, then, there’s the perspective of the silent film aficionados who view this film negatively. I certainly see their point, too; for better or worse, people are now going to view this “ode to silent cinema” as being emblematic of silent cinema, when really it is just a very strong example of its classic aesthetic in practice. Certainly, The Artist is no match for the great works of Chaplin or Keaton, nor does it display the pathos and artistic daring of The Big Parade, The Last Laugh, Metropolis, The Crowd, or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but that fault lies in the limited perspective of the audience, not the film. Really, though I do think film fans can and will appreciate it, at the end of the day, this was a film made for people who don’t know silent film, and in this respect it should be best looked at as broadening the horizons of those who mistakenly think that just because a film doesn’t have spoken dialog that it somehow makes it archaic. Perhaps the most beautiful thing about The Artist’s narrative, as corny and hackneyed as it may sometimes be, is that while people may forget the beauty and power of “silent” cinema, that its influence is still felt to this day, anywhere and everywhere there is a visual medium. In the end, just because it’s not an exemplar of the form, shouldn’t be considered a reflection of the film’s overall quality.

"The Artist" can be seen as loving ode to silent cinema, though it really shouldn't be seen as emblematic of it.

Will The Artist be this year’s Best Picture winner? Most probably, yes. Does it deserve it? Even when discarding the usual “importance bias” that I think some people rationally weigh too heavily when ascribing greatness to a work (and which in this case would be negatively weighed against The Artist), the short answer is: no. It’s an excellent, entertaining film (and a great date movie, I’m sure), but it was not the best film I saw from 2011.

To be honest, I don't knowwho I'm more in love with.

A final question I’ve seen posed and had posed to me about The Artist is: “If it weren’t a movie about movies, would critics, cinephiles, and people in the industry love this film as much as they do?” Again, the short answer: no. Films that receive true near-universal praise, however, do so because they have something that does strike a chord. Would Schindler’s List – which I grant is certainly about something a million times more important than “the movies” – have received all the love and attention it received if it weren’t for its subject matter? Would Gandhi have? Or Saving Private Ryan (oh wait, that lost to Shakespeare in Love…nice one, Oscar)? All aspects of quality being equal, I would probably respect a silent movie as great as The Artist more if it weren’t about the movies, because that would have been a far more daring thing to do. The reality is, though, that movie wouldn’t have been made. Of course, now that The Artist has been so successful, now perhaps such a movie now could be.

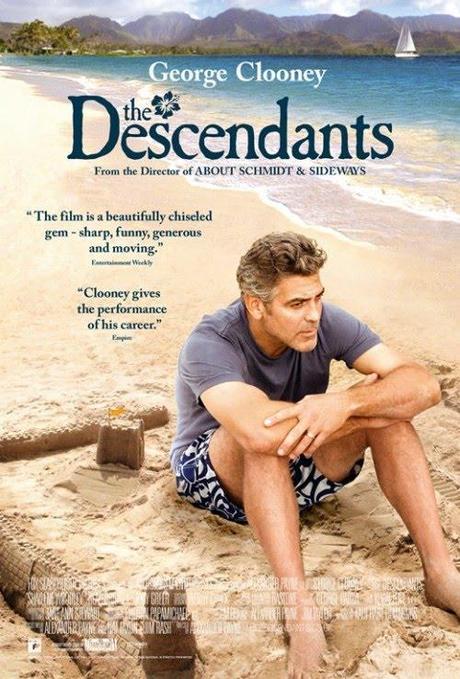

The Descendants

I did, in point of fact, already review this film here. To reemphasize though, this is a truly superb adult comedy-drama that does a remarkable job of really getting you inside the heads of its characters, almost as if you were a person sharing the scene with them, and it boasts perhaps George Clooney’s greatest performance to date (and he’s had a lot of them). Again, the film’s true greatness will be in how well it stands the test of time, but what can’t be denied are the sheer strength of its writing and the sublime poignancy of its narrative. Telling the story of a man essentially waiting to become a widower and the ways he comes to grips during that time with both his dying wife’s infidelity and his own effectiveness as a spouse and a father, this very well might have been the true best film of the year.

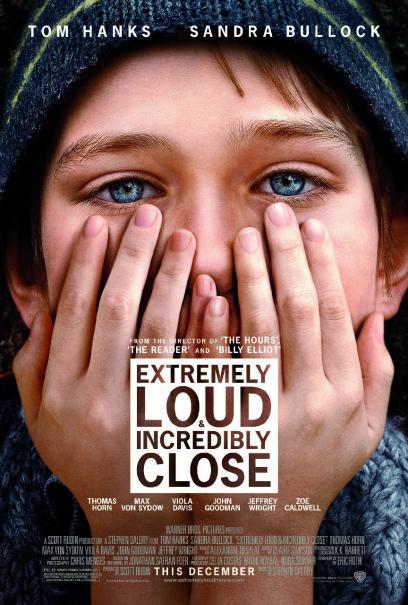

Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close

As someone who experienced September 11 in many direct and indirect ways, I undoubtedly carry a fierce sense of judgment and scrutiny towards this film, and I’m incredibly certain that I will have a lot more to say about it in some later piece. The film tells the (fictional) story of Oskar Schell, a very neurotic boy (who perhaps suffers from Asperger’s or something similar), and the strange mission he goes on as he deals with the horrific loss of his father (Tom Hanks), who died in the World Trade Center on September 11. Qualitatively speaking, this absolutely does not belong on a list of Best Picture nominees and its presence there seems only to be “justifiable” by the weight of its subject matter, to which it thoroughly fails to do justice (though I doubt there will really ever be any films could adequately do that). Though a complex narrative of strongly constructed and highly detailed characters (all of whom are very well acted, up and down the line), the film uncomfortably veers between high-minded treacle and overbearing schmaltz without anything to really say about its core subject, which ultimately reduces it to the status of a plot element. In some respects, this isn’t a film that was “too soon,” because no matter when it would have been made, I don’t think it would ever truly feel “right.” This is also the second film from director Stephen Daldry, after The Reader, that deals with historical subjects in ways that were somewhat oblivious to the pain of their narrative’s representation; it was also adapted from Jonathan Safron Foer’s novel by Eric Roth, screenwriter for Forrest Gump…and you don’t want to get me started on how I felt that movie treated history…

The Help

This is another film I will more likely than not be writing a great deal more on in the future, and in fact I’ve already dispensed with a great deal of ink (albeit of the electronic variety) on its treatment of race relations in the greater scheme of Hollywood cinema for a paper I’m hoping to present in the future. As that choice of subject matter alone would probably suggest, I’m absolutely not a fan of The Help. Looking at it, again, from a perspective of quality, it’s technically speaking not a bad movie, though it’s also not what I feel to be Best Picture nominee quality. The problems with The Help exist mainly in the fact that it’s a basic representative of Hollywood’s very problematic view of race relations. It not only portrays historical racism through the skewed viewpoint of white guilt, but then addresses and attempts to alleviate that guilt by portraying liberal whites as taking the initiative in improving the conditions of the African-American people. Essentially, it not only writes white people into the Civil Rights movement when the story of the movement was Black self-empowerment, but essentially gives them the lion’s share of the credit for the movement’s achievements. The film does boast strong performances, no doubt, with Viola Davis’s especially being awards-caliber (Octavia Spencer, while also very good, is essentially “cooning”), and some very witty writing. For the most part, however, this film doesn’t belong on this list, and I’m certain it’s only there because there are those in Hollywood who think it portrayed its historically relevant subject matter in the proper fashion. And, to be honest, that makes me kind of angry.

Hugo

Again, I’ve already written a review of Hugo here. To be clear, though, this would probably be my personal choice for film of the year, as I found it to be a genuinely emotional experience that represented the beauty and power of cinema, and NOT because it was about cinema. The film is a wonderful reflection on the importance of family, the beauty of dreams, and the often crushing burdens of life’s disappointments. It’s also the best representation of 3D filmmaking I’ve seen to date.

Midnight in Paris

I’ve seen countless wonderful films set in Paris over the years, including Hugo, as a matter of fact…but Midnight in Paris might be the first one that made me incredibly keen to actually go there someday. Also, as an often more-frustrated-than-not writer myself, this story of a modern-day, self-proclaimed hack screenwriter getting to meet his many artistic idols from 1920s Paris struck a loud chord with me personally. More than that, I also thought it represented Woody Allen’s best film in his recent, new millennium resurgence, with a wonderfully literate screenplay and a terrific assortment of great performances, including the always wonderful Marion Cotillard, Rachel McAdams, Adrian Brody, Corey Stoll, Tom Hiddleston, and Owen Wilson scoring as perhaps the best Woody surrogate we’ve had yet. Kudos to the Academy for giving Midnight in Paris some deserved recognition, even if it has no real chance of winning.

Moneyball

Yet again, I have already written a review of this here, but to reiterate that review, this is itself a fantastic film and one that probably deserves stronger consideration than it has received; which, given that it’s already a Best Picture nominee, should tell you something. As is probably already well known, Moneyball tells the story of Oakland A’s General Manager Billy Beane and the year he introduced sabremetrics to the sport of baseball. Though initially appearing to be “unfilmable,” the ultimate result is honestly just incredible. It’s a bit of a shame that Brad Pitt has to compete with both George Clooney and Jean Dujardin this year in the Best Actor category, because he delivers the performance of his career as Beane. In many respects, of all the films on this list, Moneyball may have the greatest resonance in film history, since I honestly feel that it represents the best baseball film ever made.

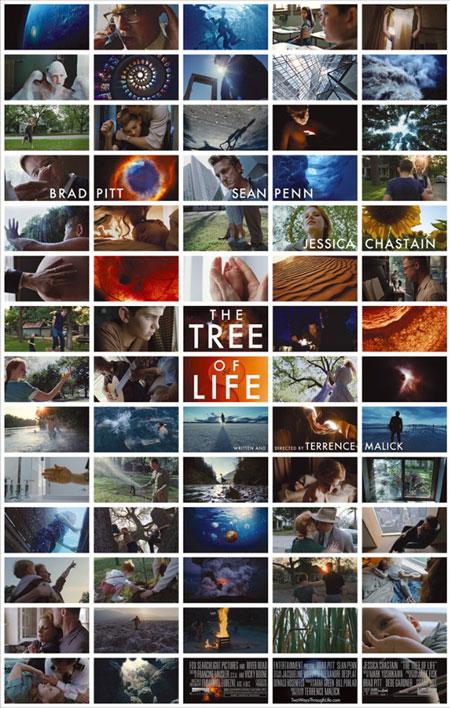

The Tree of Life

Writing this little blurb is a bit sad for me because it almost represents an omission of defeat; truth be told, I spent some significant time last month trying to write a thoughtful, analytic piece on Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, but in the end, I just couldn’t make it come together in a way I was comfortable with. Of course, there are two sides to the argument on this film: either you appreciate it, or you don’t. Granted, Tree of Life is like nothing typically seen outside of the avant garde, and it defies almost all reigning conventions in mainstream cinema. For that reason, it’s really difficult to define on those standards. I think it’s an incredible film, though, and nowhere near as “incomprehensible” as some of its critics would claim it is. With that said, it requires patience and an open mind on the part of the viewer; this is not a film that will take pains to explain everything to you or wrap everything up in a nice, neat package. Whatever answers you derive from it are answers you’ll essentially need to figure out for yourself. To me, that’s also its biggest flaw, if you can call it that, in that you can never really be sure by the outcome that it really succeeds at conveying what Malick was trying to ultimately say.

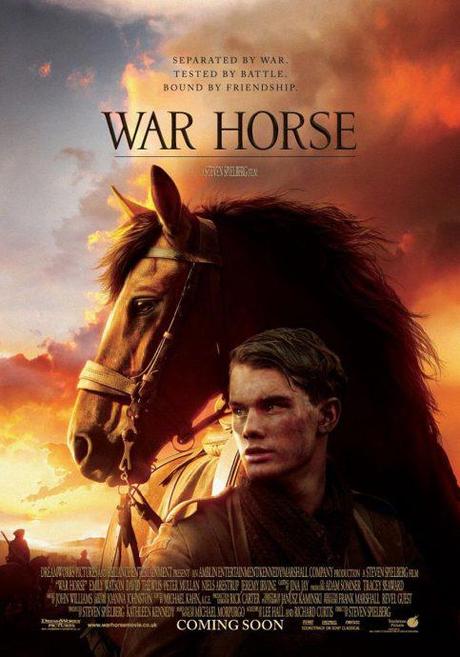

War Horse

It would be pretty easy to dismiss War Horse as Steven Spielberg’s semi-annual attempt at producing saccharine, sentimentalized Oscar bait, which is what it is, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a perfectly good movie that should easily warm your heart and bring a tear to your eye. Essentially the story of a horse and his boy, and the Great War that came between them, beyond its sentimentality this is actually very evocative piece of filmmaking about the horrors of war. While certainly not unfamiliar territory from the director of Saving Private Ryan, I was actually very, very impressed at how well it conveyed the terrible violence, pain, suffering, and sacrifice that defined the First World War while remaining within the bounds of a PG-13 rating. Personally speaking, as someone who has been a Spielberg observer his entire life, it was also nice to see him finally direct a film that didn’t simplistically vilify Germans out of hand (which is something that I’ve always felt took Saving Private Ryan down a very considerable notch). Really worth going out of your way to see, even if you’re one those people who has grown disillusioned with Spielberg over the years.

Conclusion

All told not a bad list of films, save for two very glaring inclusions, but all told they represent noteworthy exemplars in what otherwise felt like a year that was defined by films that were either very good or thoroughly underwhelming, with very little middle ground. Nevertheless what was good, was good, and given films like Hugo, The Artist, The Tree of Life, Rango, and Moneyball we saw more mainstream films willing to take some nice risks. All told, I can’t say it was a great year, but it was certainly a very, very good one and sometimes, that’s all you can ask for.