I was watching one of Michio Kaku’s Big Think videos recently that addressed American science education. The question of interest was how America continues to do so well in science and technology given that the American (primary and secondary) educational system isn’t up to par in science and mathematics with its technological competitors. The bulk of his talk (re: the H-1B visa and importation of brain power) isn’t germane to this post. It’s Kaku’s mention of a second secret weapon that caught my attention, and that’s how America is able to do a better job than many of its competitors in identifying and nurturing top talent. While math and science education is better in many Asian countries, those countries (e.g. Japan, Korea, or China) don’t excel at skimming off the cream of the crop. Dr. Kaku explains that this is because Confucian values teach students to conform, and students are loathe to stand out–even for exceptional performance. Even if a student wanted to show their talent in hopes of having it fostered, the large classes, lecture-centric teaching, and testing of memorization and standardized processes doesn’t offer much opportunity to grow one’s individual strengths.

Kaku’s statement resonated with me because I’ve been thinking about the pros and cons of traditional approaches to martial arts instruction. I’m particularly interested in the gulf between the traditional approach and what martial arts teaching would look like if one took advantage of the wealth of scientific knowledge about mind and body development. Most of the martial arts instruction I’ve received over the years is consistent with Confucian thinking. All the students are doing the same practice (or faking it to the best of each’s abilities if it’s beyond one’s current capacities), and each is trying to closely emulate the teacher-presented ideal as much as possible. There’s not much consideration of the individual student’s weaknesses or strengths. Emphasis is on trying to convey as high-fidelity a replica of the techniques that have been handed down through the ages. (While this may be a laudable goal, I’ll later offer explanations as to why I think it’s both death for retention of students and ultimately counterproductive.)

Let me first say that there are a number of advantages to the traditional approach to martial arts instruction. First, it’s easy to teach many students at once. This was probably a huge advantage when there were armies of men having to learn these skills. Second, [theoretically] it helps students reduce their egotism through discipline and conformity. The highly hierarchical nature of this approach means students spend years in a lowly position, with the hope that some humility may stick. (NOTE: I’m not certain that this works out in practice.) Third, it creates a disciplined learning environment that is conducive to helping a student keep his or her head in the game.

What the traditional approach isn’t so good at is producing students who all perform at the best of their abilities. I suspect that the traditional approach doesn’t do so well for student retention either. It’s a system in which new students are forced to drink through the fire-hose; while students who’ve been around for a while often feel like they’re stagnating. As I’ll get to below, there’s good reason to believe that a proper match between the challenge of a task and the performer’s skill level is critical to creating an intrinsically rewarding activity and to helping students perform at their best.

My thoughts on this topic have been heavily influenced by learning and teaching yoga. While one’s vision of a yoga class may be rows of students doing the exact same posture (and huge classes and / or poor instructors may result in that condition), but there’s often a degree of variation in a class. This variation results from two concepts that I’ve been thinking about quite a bit lately, namely modifications and capacity building.

Modifications are a two-way street. If the task at hand is beyond the student’s current abilities, he or she may be given an easier variant that allows him or her to work toward the fundamental form. On the other hand, if the task of the moment is old hat, a student might be offered a more challenging version on occasion. I’m not suggesting that one shouldn’t drill the basics throughout one’s martial arts career. Repetition of fundamentals is key to drilling them down into one’s nervous system. However, the brain loves novelty and hates drudgery, and it will become harder and harder to remain engaged if the overall challenge level doesn’t rise. The science suggests that one needs to keep upping one’s game if one wants to perform at one’s best.

The nature of modifications in martial arts may not seem as clear as it is with respect to yoga postures. For randori, sparring, and other free-form training, it’s easy to envision how one can adapt the practice to reduce or increase the challenge to a level more apropos of the student’s skill level. One can practice a restricted form. For example, one may work only on sparring with boxing rules to kicks or grappling out of the equation until a student builds up his or her confidence and abilities with recognizing and responding to punches. Alternatively, an advanced student might be presented with armed or multiple attackers. There are some practices, such as specific techniques, for which modifications may not be an option, but that doesn’t necessarily let a teacher off the hook for helping a student who’s challenged by the technique. That may be where capacity building exercises come into play.

Capacity building goes beyond offering an easier modification to suggesting exercises to help the student build the physical capacity to do the technique repetitively WITHOUT INJURY. I emphasized those last two words for a reason. In some martial arts, the need for capacity building exercises maybe clear because of the acrobatic insanity involved. However, practitioners of more pragmatic martial arts may say, “We don’t do all those fancy spinning back kicks, so we don’t need capacity building. Anybody can do our techniques because they’re simple and direct.” Maybe that’s true, but if multiple members of your school have the same (or similar) repetitive stress injuries, it’s not true at all.

What kind of capacity building are we talking about? If the technique involves jumping or leaping and the individual is gravitationally-challenged, then plyometrics might be the prescription. On the other hand, if the problem is the inability of the student’s joints to withstand the technique, there might be need for exercises that build up stabilizing muscles, help him / her to cut weight, or both. If a student can’t do a throw without risk of injury, maybe that individual needs to spend time practicing with elastic bands or inner tubes or working on their balance.

There are conditions that favor achievement of Flow, notably: 1.) clear goals, 2.) immediate feedback, and 3.) a good match between the level of the challenge and the level of one’s skill. Flow is a key factor in why some activities are intrinsically rewarding (whether or not they are rewarding in other ways) and why almost any activity can be intrinsically rewarding if it’s sufficiently challenging relative to one’s abilities. What’s sufficiently challenging? That’s where 4% comes into the picture. While it’s by no means an exact or universal value, it turns out that when a task presents a challenge that is roughly 4% above one’s present skill-level is when this state of mind is most accessible. This is why one may see students drop out if they find the level of challenge stagnant. On the other hand, one may not keep new students either if the challenge is constantly beyond their abilities.

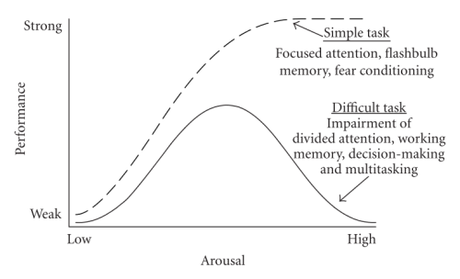

How about that Yerkes-Dodson? The two early 20th century scientists for whom the Yerkes-Dodson Law are named discovered that performance increases with arousal (one might do best to think of this as anxiety level rather than the colloquial use of that word) up to a certain point, beyond which performance either levels off or plummets–depending upon the nature of the objective. The point is that keeping the training environment too sterile has it’s disadvantages. In free-form practices like sparring, a little nerves can be a good thing, but being overwhelmed can be detrimental.

Yerkes-Dodson Curves. Source: Wikipedia

Adjusting one’s instruction to the abilities of one’s students is challenging. Traditionalists may hold that it’s far more important to keep the tradition intact than it is to cater to the individual needs of students. That is, said teachers may prefer to focus on the aforementioned high-fidelity transmission of the teachings of the lineage. There was a time during which I probably would have echoed that sentiment. However, it increasingly occurs to me that producing the best and most engaged students is the best way to keep a tradition alive.

By B Gourley in exercise, fitness, martial arts, Movement, science, sports on July 29, 2015.